eBook - ePub

Singing and Wellbeing

Ancient Wisdom, Modern Proof

Kay Norton

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Singing and Wellbeing

Ancient Wisdom, Modern Proof

Kay Norton

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Singing and Wellbeing provides evidence that the benefits of a melodious voice go far beyond pleasure, and confirms the importance of singing in optimum health. A largely untapped resource in the health care professions, the singing voice offers rewards that are closer than ever to being fully quantified by advances in neuroscience and psychology. For music, pre-med, bioethics, and medical humanities students, this book introduces the types of ongoing research that connect behaviour and brain function with the musical voice.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Singing and Wellbeing est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Singing and Wellbeing par Kay Norton en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Media & Performing Arts et Music. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Singing in History, Cognition, and Parenting

1

The First Musical Instrument

The melodious range of the voice contains the therapeutic capsule.

George Rousseau (2000, 108)

This chapter begins with a look into human evolution and several theories about singing behaviors in our pre-human ancestors. Next, I explain why we have a clearer idea about the evolution of musical instruments than we do about the development of vocal music. The chapter ends with an exploration of the anatomical source of the voice: a physical apparatus activated by the breath. As important as basic anatomy is to vocal production and its powers over humans, the ways song, chant, and lyrical speech are individualized with inflection, pitch range, and language are equally central to the moving power of the voice. The writings of philosophers, poets, and an iconic civil rights leader provide evidence that the voice is an expressive tool—a musical instrument—whose power over humans may be traced to its roles in identity, communication, and persuasion.

Singing in Pre-human Ancestors

Music, including the inflected vocal utterance we call “song,” appears in all human cultures and is therefore essential to an understanding of our evolution. As with other persisting behaviors, the concept that music was a fitness advantage in evolution must be considered; otherwise, song would have arisen and disappeared over millennia of development. Just how far back does song extend in the ancestry of Homo sapiens? Though we no longer can study living, early-stage humanoids, we can study living non-human species whose partial evolutionary trajectory we share. In addition, evolutionary biologists actively study song characteristics of unrelated species such as birds to understand which contexts may apply to human singing behavior (Lipkind et al. 2013). In these ways, a view of singing’s global value materializes.

In this discussion I adopt W.H. Thorpe’s definition of song relevant to songbirds: “What is usually understood by the term song is a series of notes, generally of more than one type, uttered in succession and so related as to form a recognizable sequence or pattern in time” (Thorpe 1961, 15).1 From Thorpe’s perspective, the world is full of non-human songs. Surely all this singing behavior is somehow connected; anthropology offers various ways to discover those connections. Nils L. Wallin was a researcher committed to understanding music in its entire terrestrial sense. He coined the term biomusicology to describe a field in which the origins of music are considered crucial to the study of human origins (Wallin 2000, 5). Music and language were considered close relatives in prior evolution studies, but, before the 1990s, scientific interest centered mainly on the place of language in human evolution. Wallin and co-editors Björn Merker and Steven Brown presented research by twenty-five other scientists and musicologists in the 2000 book The Origins of Music. These authors contributed important biomusicological perspectives on music making; works devoted to song are especially enlightening.

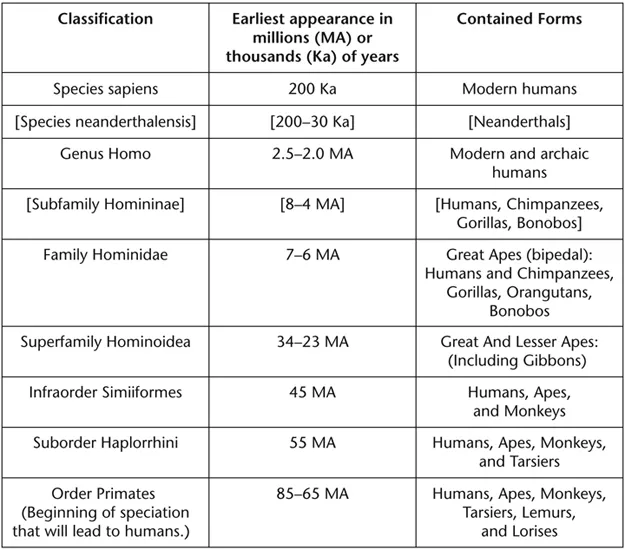

Figure 1.1 General dating of bifurcation events in the primate phylogeny.

Note: Dating estimates based on DNA evidence, fossil records, generation times, and other methods are not always compatible. Dates in this chart are therefore general.

Despite differences among the sound-producing mechanisms of, for example, the great whale, Old World monkeys, and the western meadowlark, ongoing research on “vocal” usages among animals presents behavior analogous to that of modern humans in developed societies (Tobias and Seddon 2009). And while singing behavior among primates is quite rare, it has been found in the evolution of four distantly related, non-human primate species: gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, and chimpanzees (see Figure 1.1). The chimpanzee, our closest non-human relative, shares with humans a larynx that repositions during the first two years of life to a spot between the pharynx and the lungs.2 Our common ancestors also had this feature, a precursor of speech, as long ago as seven million years.

Thomas Geissmann proposes several potential fitness advantages of singing in gibbons and among other apes. Male orangutans utilize lengthy calls partly because they can be heard over long distances, and their calls may mediate inter-individual spacing. In other words, a male may emit these calls to help advertise his territory and intimidate competitors (Geissmann 2000, 115, 119). Gorilla “hoot” series seem to serve long-range group communication, and other vocalizations may provide long-range alarm systems. Loud calls of other primate species may also help locate specific individuals and food sources. Finally, loud calls may strengthen intergroup cohesion. Geissmann suggests the possibility that

early homonid singing shared many characteristics with loud calls of modern Old World Monkeys and especially apes, such as loudness (for long-distance communication), pure tonal quality of notes, stereotyped phrases, biphasic notes (making sound on the in-breath and the out-breath), accelerando (increasing in speed), possible slow-down near the end of a phrase, locomotor display, and a strong inherited component.

Geissmann (2000, 118)

Geissmann then proposes the obvious: “It makes sense to assume that. . . loud calls of early hominids may have been the substrate from which human singing and, ultimately, music evolved” (Geissmann 2000, 118). Hypothetical though it may be, that statement is worth contemplating further. Could singing behavior, which carried with it several fitness advantages, partially explain the evolution of Homo sapiens sapiens into the most powerful and cognitively advanced species on the planet? How might singing have advantaged our evolutionary line to develop a cognitive potential greater than that of hominid substrates such as Old World monkeys?

One way that humans surpassed our primate ancestors musically was in developing a steady pulse or beat.3 Geissmann suggests that regularly pulsed group participation and coordination may be considered a fitness advantage; a coordinated display may be impressive to interlopers and a steady beat signals group cohesiveness to competing groups (Geissmann 2000, 119). It therefore seems reasonable to imagine that early human survival and success in competition evolved into a preference for a rhythmically coordinated vocal display. Humans in groups survive better than loners; highly vocal groups cohere (aided by, among other things, a steady beat) and therefore survive better than less vocal or less vocally cohesive ones. Geissmann’s hypothesis, that the best fitness advantage was evolutionally associated with the most vocal, coordinated human groups, seems plausible given the persistence of singing in our species.4

Charles Darwin (1809–82) believed that music and singing evolved as part of courtship displays and that, as with coloration in birds, the male evolved to be most expressive in order to attract the best mates. In “Evolution of Human Music through Sexual Selection,” Miller updates Darwin’s courtship hypothesis to help explain the persistence of music in human evolution. Restating the truth that music-making could not have persisted simply because it is a vehicle of self-expression, he notes that “most animal signal systems have been successfully analyzed as adaptations that manipulate the signal receiver’s behavior to the signaler’s benefit” (Miller 2000, 336).5 If, as Miller argues, most of what an animal does is aimed at influencing the behavior of another animal, why has music become so specialized in humans?

Calling upon the work of another predecessor, Miller recounts R.A. Fisher’s 1930 theory of runaway sexual selection, to wit: female preference for lowest-sounding male mating calls would eventually result in offspring that both preferred low-sounding male voices and had capacities to make low sounds (Fischer 1930). Although widely disputed, the idea of a fitness advantage linking female preference for low-voiced males and pubescent male vocal change is fascinating to consider. Fitch and Giedd call the descent of the larynx in pubescent human males “a sexually dimorphic. . . adaptation to give adult males a more imposing and resonant voice relative to females or prepubescent males” (Fitch and Giedd 1999, 1517). It “might represent a. . . means of exaggerating vocally projected body size, and its restriction to males suggests that it is. . . the acoustic equivalent of. . . secondary sexual characteristics seen in males of many other species,” such as lions’ manes, bisons’ humps, and orangutans’ cheek pads (Fitch and Giedd 1999, 1520).

To summarize, Miller writes: “Music is what happens when a smart, group-living, anthropoid ape stumbles into the evolutionary wonderland of runaway sexual selection for complex acoustic displays” (Miller 2000, 349). He believes that, even though humans engage in music in groups, the persistence of vocalizing in human evolution is not group oriented. Instead, Miller believes group vocal engagement among humans is valuable for its mood-calibrating purposes and as another facet of sexual selection. Performing in a group under prehistoric conditions meant one was part of a successful band that shared health, energy, capacity to coexist, and a common language (Miller 2000, 353).

Other contributors to The Origins of Music—Peter Marler (“Origins of Music and Speech: Insights from Animals”), Peter J.B. Slater (“Birdsong Repertoires: Their Origins and Use”), Harry Jerison (“Paleoneurology and the Biology of Music”)—help underscore the relevance of animal singing behavior when parsing the evolution of human music. Evolutionary musicology—like anthropology—proceeds from incomplete, surviving knowledge and posits theoretical models from those key factors, and as The Origins of Music editors write, “There is no a priori way of excluding the possibility. . . that our distant forebears might have been singing homonids before they became talking humans” (Wallin 2000, 7, emphasis mine). The following section elucidates the reasons anthropologists must rely on speculation in order to construct a history of human singing.

The Elusive Documentation of Vocal Music

Although some might argue that purposefully striking sticks or rocks together pre-dated the first musical sounds from the voice in human evolution, this book rests on the reasonable assumption that singing was our first musical expression. As with any ephemeral product of culture, music history begins with mythology.6 The Greek god Orpheus, both instrumentalist and singer, wielded power over the living and the dead, human and divine.

While he sang. . . to the sound of his sweet lyre, the bloodless ghosts themselves were weeping, and the anxious Tantalus stopped clutching at return-flow of the wave, Ixion’s twisting wheel stood wonder-bound; and Tityus’ liver for a while escaped the vultures, and the listening Belides forgot their sieve-like bowls and even you, O Sisyphus! sat idly on your rock! Then Fame declared that conquered by the song of Orpheus, for the first and only time the hard cheeks of the fierce Eumenides were wet with tears: nor could the royal queen, nor he who rules the lower world deny the prayer of Orpheus.7

Ovid in More (1922)

Without doubt, ancient people sang, but because the soft tissues of hominid vocal mechanisms almost never survived to be studied by archeologists, evolution of the vocal mechanism has remained unclear. Singing neither required an external device, nor left an artifact; for documented origins of singing, we must be satisfied with the oldest notated song. In 1974, cuneiform expert and philology professor Anne Draffkorn Kilmer reported that the oldest notated song to date was found on a tablet of “Hurrian cult songs from the ancient Levantine city of Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra), dating to the middle of the second millenium BCE,” almost 1,000 years prior to the earliest Greek musical notation (Kilmer 1974, 69). Even older—dating to as early as the middle of the third millennium BCE—are “early Dynastic lists of professions (‘Early Dynastic Lu’) which provide us with the core of the musicological terms for singers and instrumentalists” (Kilmer 1971, 148).8 But how long did people sing before they felt the necessity to write songs down?

The history of musical instruments is somewhat of a different story, though the earliest stories are also mythological. “Pan is credited with the invention of the pan-pipes,” wrote Curt Sachs, “and Mercury is supposed to have devised the lyre when one day he found a dried-out tortoise on the banks of the Nile” (Sachs 1940, 25).9 Archeologis...