![]()

1

Historical, Contemporary, and Future Perspectives on Self-Regulated Learning and Performance

Dale H. Schunk and Jeffrey A. Greene

Recent years have seen tremendous advances in theory development, research, and practice relevant to the field of the self-regulation of learning and performance in educational settings. As used in this volume, self-regulation refers to the ways that learners systematically activate and sustain their cognitions, motivations, behaviors, and affects, toward the attainment of their goals. The distinction between self-regulation of learning and self-regulation of performance is that in the former the goals involve learning.

As this volume makes clear, there are numerous theoretical perspectives on self-regulation that have relevance to educational settings. Regardless of perspective, however, these perspectives share common features. One feature is that self-regulation involves being behaviorally, cognitively, metacognitively, and motivationally active in one’s learning and performance (Zimmerman, 2001). Second, goal setting and striving trigger self-regulation by maintaining students’ focus on goal-directed activities and the use of task-relevant strategies (Sitzmann & Ely, 2011). Goals that include learning skills and improving competencies result in better self-regulation than those oriented toward simply completing tasks (Schunk & Swartz, 1993). A third common feature is that self-regulation is a dynamic and cyclical process comprising feedback loops (Lord, Diefendorff, Schmidt, & Hall, 2010). Self-regulated learners set goals and metacognitively monitor their progress toward them. They respond to their monitoring, as well as to external feedback, in ways they believe will help them attain their goals, such as by working harder or changing their strategies. Goal attainment leads to setting new goals. Fourth, there is an emphasis on motivation, or why persons choose to self-regulate and sustain their efforts. Motivational variables are critical for learning, and can affect students’ likelihood of pursuing or abandoning goals (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2008). Lastly, emotions play a key role in both directing self-regulation as well as in maintaining energy to attain goals (Efklides, 2011).

Since the first edition of the Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011), many exciting developments in the field of self-regulation have occurred. But the purpose of this second edition remains the same as that of the first: to provide readers with self-regulation theoretical models, principles, research findings, and practical applications to educational settings. To accomplish this purpose, we have assembled an outstanding group of scholars to contribute chapters. The Handbook is divided into five major sections: basic domains, context, technology, methodology and assessment, and individual and group differences. As a means of promoting some consistency across chapters, we have asked contributors to address four major topics in their chapters: key theoretical ideas, pertinent research evidence, future research directions, and implications of theory and research for educational practice. We believe that this organization of topics and consistency across chapters will assist readers’ understanding of the important topics discussed.

New developments are outlined in all five sections of this Handbook. For example, since the last Handbook, theoretical refinements have been proposed, new instructional issues have arisen as researchers apply self-regulated learning outside of traditional educational learning settings, advances in instruction and intervention have changed approaches to developing learners’ capabilities to self-regulate, methodological advances have been developed, tested, and implemented, and researchers have expanded their investigation of the role of learner differences in such areas as contexts and cultures. This second edition not only updates developments since the first edition but also reflects new directions in the field.

In this introductory chapter, we address key historical, contemporary, and future developments in the field. We also briefly summarize the chapters that follow, and identify important directions for future research. The next section discusses historical perspectives on self-regulation of learning and performance in educational contexts.

Historical Perspectives

The impetus for studying self-regulation in educational settings arose from diverse sources (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011). Beginning in the 1970s, cognitive-behavioral researchers studied how to improve students’ self-control (e.g., control of impulsivity) and thereby their academic learning. Cognitive-behavioral methods were implemented in interventions and included the use of self-instruction and self-reinforcement. From this perspective, self-regulation comprised ways individuals controlled the antecedents and consequences of their behaviors, as well as their overt reactions such as feelings of anxiety (Thoresen & Mahoney, 1974). Self-instruction, which included learners’ modeled verbalizations and behaviors, followed by guided practice and the fading of verbalizations to a covert level, was shown to be effective in promoting students’ task focus and achievement (Meichenbaum & Asarnow, 1979).

Another group of researchers approached self-regulation from a cognitive-developmental perspective. Although young children show genetic differences in their behavioral control, with development language plays a greater role in self-regulation. Vygotsky (1962) postulated a developmental account in which the speech of others in children’s environments is internalized (i.e., adopted as their own) and then assumes a covert self-directive function (Diaz, Neil, & Amaya-Williams, 1990). A key conceptualization is the zone of proximal development, which describes how higher levels of functioning can be achieved with support (i.e., scaffolding) from others. Language becomes internalized in the zone of proximal development and assumes a self-regulatory role.

Another developmental topic relevant to self-regulation is delay of gratification (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011). With development, children can better resist immediate rewards in favor of greater rewards associated with time delays (Mischel, 1961). Delay of gratification is important for self-regulation because it allows learners to set and pursue challenging but rewarding distal goals, and effectively cope with potential briefly-gratifying distractions and instead focus on learning tasks.

A third group of researchers examined metacognitive and cognitive issues (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2011). These researchers showed that students could be taught task strategies that improved their academic performances, although maintenance and transfer of the strategies over time and to new tasks often were all too rare (Pressley & McCormick, 1995). Simply teaching strategies did not guarantee their use. Researchers examined ways to promote strategy use such as by informing students of the effectiveness of the strategies and showing them how use of the strategies improved their performances (Schunk & Rice, 1987). Metacognitive knowledge and skills were also viable targets for instruction. This research revealed that, in addition to cognitive and metacognitive skills, motivation also is necessary to promote self-regulation (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2008).

Social cognitive researchers explored social and motivational influences on self-regulation. In Bandura’s (1986) theory, self-regulation involves three phases: self-observation, self-judgment, and self-reaction. During self-observation learners monitor aspects of their performances; self-judgment involves students comparing their performances against standards; and self-reactions include their feelings of self-efficacy (i.e., perceived capabilities) and affective reactions to their performances (e.g., satisfaction). Social cognitive researchers showed that instructional processes such as modeling conveyed information to learners about their learning progress and raised their self-efficacy and task motivation (Schunk, 2012).

The research described in this section was conducted by different researchers operating in different domains. Despite this diversity, however, these research findings, combined with symposia at major conferences (e.g., American Educational Research Association in 1986), gave rise to the perceived need for integrated perspectives on self-regulation. This integration set the stage for researchers to systematically explore self-regulatory processes in educational contexts.

Self-Regulation Research in Education

It is not possible to put an exact date on when systematic efforts began to explore the self-regulation of learning and performance in educational settings, but by the 1980s integrated models were being advanced and research on self-regulation was increasing (Zimmerman, 1986). The time from the mid-1980s to the present can be roughly divided into three periods, each characterized by dominant theoretical, empirical, and practical issues. This categorization runs the risk of oversimplifying, and we are not implying that the model listed for each period was the only one employed. Clearly many research issues were addressed in each period. The periods also do not neatly demarcate; there are overlaps. But this categorization summarizes the dominant issues of these periods, which we label the periods of development, intervention, and operation.

Period of Development

The period of development began in the 1980s and stretched well into the 1990s. During this time, researchers were highly interested in developing theories to guide research and methodologies to employ in that research. Theories reflecting the cognitive-behavioral, social cognitive, cognitive-metacognitive, social constructivist, and cognitive-developmental research traditions were formulated and refined.

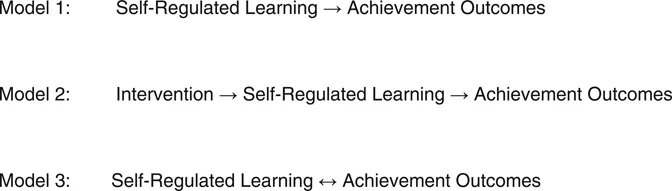

As shown in Figure 1.1, the period of development was characterized by a research model that emphasized the relation of self-regulation to outcomes such as achievement beliefs, affects, and behaviors (Model 1). Many researchers investigated which self-regulation processes students used and how this use related to outcomes. These early studies often involved self-report instruments such as questionnaires or interviews to determine the types of processes that students reported they employed, as well as how often they reported their use and in which contexts (Schunk, 2013). Commonly used instruments were the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire or MSLQ (Pintrich, Smith, Garcia, & McKeachie, 1991, 1993) and the Learning and Study Strategies Inventory or LASSI (Weinstein, Palmer, & Schulte, 1987). These and other instruments, which displayed strong psychometric qualities, served to operationalize self-regulation processes.

A representative study from this era was conducted by Zimmerman and Martinez-Pons (1990) with students in regular and gifted classes in grades five, eight, and eleven. Using a structured interview, students were presented with scenarios such as, “When taking a test in school, do you have a particular method for obtaining as many correct answers as possible?” (Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons, 1990, p. 53). For each scenario, students described the methods they would use. Their responses were recorded and categorized into ten categories such as self-evaluating, goal setting and planning, rehearsing and memorizing, and reviewing. Results revealed that students in gifted classes reported using more self-regulatory strategies than regular-education students and that the frequency of strategy use increased with grade level.

There were many accomplishments during this period of development. Researchers refined theories and research methodologies to fit educational contexts, identified key self-regulation processes in those contexts, and drew implications of their research findings for educational policies and practices. At the same time, however, there were some issues. Self-report instruments captured students’ perceptions of their self-regulation at a given time but were limited in their ability to capture self-regulation’s defining dynamic and cyclical nature; that is, how learners change and adapt self-regulation processes while they are engaged in learning in response to their perceived progress and to changing conditions. And because much of the research conducted was correlational, causal conclusions could not be drawn, which meant that researchers could not conclude that self-regulation helped to promote achievement outcomes.

Figure 1.1 Research paradigms commonly used in self-regulation research in education

Period of Intervention

The period of intervention stretched roughly from the late 1980s through the 1990s and into the 2000s. During this time, researchers investigated how to teach students self-regulation processes, how students used them, how their use influenced achievement outcomes, and whether their use was moderated by other variables such as learners’ abilities and context (e.g., individual differences, culture). The research model reflected this causal sequence (Figure 1.1, Model 2): Interventions were predicted to influence self-regulation, which in turn affected achievement outcomes. For example, researchers might administer a pretest to assess students’ skills and self-regulatory processes, and then introduce an intervention in which students were taught self-regulation strategies and then practiced applying them. Follow-up assessments determined whether treatment students applied the strategies with more frequency or quality than control students, and how self-regulation strategy use related to achievement outcomes.

This methodology is illustrated in a study by Schunk and Swartz (1993). Fourth and fifth graders were taught a multi-step strategy for writing different types of paragraphs. They were pretested on self-efficacy for paragraph writing, writing achievement, and self-reported use of the strategy’s steps when they wrote paragraphs. They received modeling, guided practice, and independent practice on applying the strategy to write paragraphs. Children were given either (a) a goal of learning to use the strategy to write paragraphs, (b) an outcome goal of writing paragraphs, (c) a learning goal plus feedback during the sessions linking their performance with strategy use, or (d) a general goal of doing their best. Participants were tested after the intervention, as well as six weeks later with no intervening strategy instruction. In addition, a maintenance test was given where children verbalized aloud as they wrote a paragraph, with verbalizations recorded and scored for use of the strategy. The learning goal with feedback yielded the greatest benefits in terms of skill, self-efficacy, and strategy maintenance. The learning goal was more effective than the outcome and general goals.

Intervention studies captured some of the dynamic nature of self-regulation. They also could assess causality because they showed how students’ self-regulation changed as a result of an intervention, with some designs allowing data collection while the intervention was ongoing. But most interventions of this period did not assess real-time changes reflecting self-regulation’s dynamic nature, such as learners adapting their approaches while engaged in tasks. Such measures better reflect theoretical models that posit a continuous dynamic process.

Period of Operation

Investigators’ desire to explore self-regulation in greater depth led to the period of operation, which began in the 1990s and continues today. Investigators explore the operation of self-regulation processes as learners employ them and relate mo...