![]()

PART I

Promoting Value Congruence

![]()

1

CHALLENGING THE BINARY

Brad Harrington, the executive director of the Boston College Center for Work & Family, cautions that some women have simply grown accustomed to making imperfect trade-offs between work and their personal lives adding to the dissonance, stress, and anxiety involving the need to face a constant dilemma or make tough choices (Robbins, n.d.). On the one hand, upward obligations toward parents will pull women (especially in the 41–55 age bracket, the “sandwich” generation, positioned between growing children and aging parents) to care for their elderly parents.1 On the other hand, downward obligations to children would probably deter highly-educated women from pushing their career to the maximum because they feel torn between spending time with the family and work responsibilities. Termed “the rug rat race,” economists Garey and Valerie Ramey (2010) of the University of California, San Diego, showed that the increased scarcity of college acceptance and selection rates appears to have heightened rivalry among parents, which takes the form of extra time spent on college preparatory and extracurricular activities. It is for this reason that the most educated parents spend the most hours parenting, even though they are giving up the most in wages by doing so. When considering this broader workforce issue, the constructs are often referred to as work–life conflict and work–life enrichment. This will be elaborated on in subsequent sections.

Importantly, the types of interactions between work and life represented by these constructs are not conceptualized as mutually exclusive. That is, an individual can have both work–life conflict and work–life enrichment. For example, employees seeking to engage in their careers and families can, on the one hand, experience conflict when the time they need to be at work conflicts with their ability to attend a family event, while also experiencing enrichment when time spent at work builds their sense of self, which then can lead to positive interaction in their family life. Similarly, employees seeking to attain advanced degrees in order to enhance their marketability can experience conflict when they need to work evenings or weekends and also have course assignments to complete, while also experiencing enrichment when they can see how their work experience enhances their understanding of course concepts.

These situations can potentially present a confusing dilemma that makes it difficult for individuals to assess and articulate smart (but hard) choices for their personal and professional lives. That is, individuals are likely to feel that they need to decide between two positive options, while choosing either one over the other can have extremely negative consequences. Particularly in the case of women, the paradoxical choices are often presented as two extreme ends of a continuum: Should a woman focus on her career or on her family? In a broader employee context, the paradoxical choice may emerge as a question of whether a promotion will result in conflict (e.g., less flexibility in work schedule that has a negative consequence for time for personal interests) or enrichment (e.g., greater sense of satisfaction in professional life that has positive consequences in personal life). In addition to work–family conflict bias, women are also faced with role traps, stereotypes, tokenism, and subconscious biases (Belasen, 2012) that present high-potential women with enormous challenges including:

• Unequal expectations (double bind)—Women trying to advance in their careers often find themselves in a double bind. They have learned that they need to act and think like men to succeed, but they are criticized when they do so. The band of acceptable behavior is much more narrow for women than for men. When women managers are assertive and competitive like their male colleagues, they are often judged in performance reviews as being too tough, abrasive, or not supportive of their employees.

• Glass ceiling—An invisible barrier that separates women and minorities from top leadership positions. They can look up through the ceiling, but prevailing attitudes are invisible obstacles to their own advancement.

• Opportunity gap—The lack of opportunities. In some cases, people fail to advance to higher levels in organizations because they haven’t been able to acquire the necessary education and skills.

• Pipeline condition—The untested explanation that women leaders with the appropriate skills sets and abilities are very scarce in addition to the fact that mission-critical jobs go to men.

Hewlett (2007) pointed out that nearly four in 10 highly qualified women (37%) reported that they have left work voluntarily at some point in their careers. Women not only stay away from seeking management positions due to lack of workplace flexibility (15%) and family as a bigger priority (26%) but also because of institutional barriers (42%), less willingness to take risks (10%), and lack of mentoring and social support (7%).2

“Have it All”

It is true that women face a catch-22 regarding the path they take with their lives, as criticisms seem to amount from both directions: professional and social networks. Women who attempt to combine work responsibilities with family are either chastised for compromising their familial obligations, or for hindering their full professional potential by spending time and effort around their personal life. Lisa Belkin (2003) of the New York Times pointed out an alarming trend—large numbers of highly qualified women dropping out of mainstream careers. Labeled as the “opt-out revolution,” she traced the reasons and provided evidence why women steer off-ramp or downshift (by moving to less fast-paced jobs to accommodate family needs) at some point on their career highway. The phenomenon of “opt-out” mothers has been a subject of much media fascination—the idea that such ambitious, professionally successful women would put their careers aside, for the opportunity to focus on their families seemed to really strike a chord.

The truth is the exact opposite. Women faced limited options at work. They failed to realize their aspirations for combining career and family. They suffered a profound loss of identity, not to mention earnings and economic independence. They resumed their careers, but often with considerable redirection to fields less prestigious and less lucrative than their former ones. Theirs were not stories of flow, but of dislocation and personal cost. Employers bore costs too: the loss of highly skilled professional talent, the loss of diverse voices and experiences, and, because women left mid-career just as they were poised for ascent, the loss of women’s leadership.

(Stone, 2013)

Can the conflicting messages represented recently by Anne-Marie Slaughter and Sheryl Sandberg—“women can’t”/“women can” be reconciled (Williams, 2012)? Conveying a message that highlights the possibility and benefits of work–life integration is definitely advantageous in focusing on women’s leadership and a healthy outlook on one’s personal life. The practicality of this focus makes it both encouraging and relatable for women in addition to reinforcing the idea that women do not need to ignore one aspect or attain perfection in both to feel like they “have it all.”

Women face two life-long developmental tasks: the internal work of forming a vocational identity, and the external work of navigating a career. For women, accomplishing those tasks is complicated by a dilemma imposed by conflicting prescriptions about gender roles – between ambition (choosing a goal and going all-out for it) and drift (taking whatever comes along).

(Gersick, 2013)

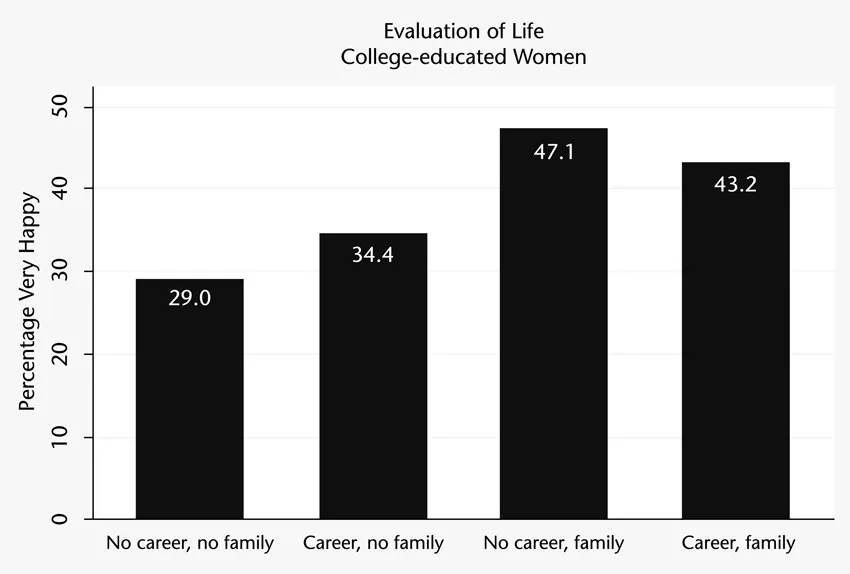

Are those women who have succeeded in “having it all” any more satisfied with their life than the women who have not met this double goal? Do they experience greater emotional well-being? While there are life satisfaction premiums for career and family individually, there is no additional premium associated with “having it all.” A study by Bertrand (2013) found that for the subset of women over 40 years of age who have nearly completed their fertile cycle, the career–life satisfaction premium becomes smaller and is no longer statistically significant. Intuitively, women that “have it all,” who are able to meet both professional and personal goals, should report higher levels of well-being. Yet, there are multiple arguments as to why these intuitive answers may not be correct such as changes in life circumstances. It is also possible that highly-educated women might attach different utility values to “having it all” due to their higher social status and greater sense of purpose, even though their well-being scores may not be higher than that of other women who steered toward not maximizing personal values. Bertrand (2013) concluded that there is no evidence of greater life satisfaction or greater emotional well-being among those that have achieved the double goal of combining a successful career with a family life (see Figure 1.1 and Table 1.1).

Less Important Roles

The glass ceiling is a metaphor that explains the subtle, invisible obstacles women face when they try to move up to senior management but are unable to pass through middle management. Oakley (2000) described the glass ceiling as not just one wall that women strive to shatter, but many varied pervasive forms of gender bias that occur frequently in both overt and covert ways. Ultimately, women who seek top management positions must sort through culturally formed stereotypes and at the same time avoid crossing culturally generated barriers.

FIGURE 1.1 Life Satisfaction Among College-educated Women

Source: Bertrand (2013).

TABLE 1.1 Emotional Well-being Among College-educated Women. Panel A: Career and Husband

Dependent variable: | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Over the Course of the Day, Average: |

| Happiness | Sadness | Stress | Tiredness |

Career | 0.088 | –0.357 | –0.052 | –0.21 |

| [0.121] | [0.098]13 | [0.141] | [0.151] |

Married | 0.259 | –0.406 | –0.332 | –0.019 |

| [0.109]* | [0.088]14 | [0.127]15 | [0.136] |

Career and married | –0.317 | 0.567 | 0.349 | 0.379 |

| [0.146]* | [0.118]16 | [0.170]* | [0.181]* |

Observations | 1482 | 1483 | 1483 | 1483 |

R-squared | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

Source: Bertrand (2013).

Eagly and Carli (2007) termed the labyrinth to describe the complicated, exhausting challenges that women must navigate in pursuit of senior positions. Although gains have been made in many employment areas, women remain significantly underrepresented in positions of power. Women are more likely to be siloed into staff positions such as corporate communication, human resources, and diversity and inclusion and they often play key roles in marketing and customer relations primarily due to their superior people and communication skills in these areas (Belasen, 2012). In addition, women are encouraged to work in departments that have fewer developmental or growth opportunities or do not translate to executive advancement (Guerrero, 2011). Contrast the siloing of women into staff positions with profit and loss responsibilities that are often reserved for men, supporting their upward mobility aspirations.

The fact remains that women are sparsely represented at the upper echelons of business and by 2015 held only 20 (4.0%) of CEO positions at S&P 500 companies, corroborating the substantial evidence of implicit bias against women leaders. Women tend to be viewed as lacking the requisite skills to lead a large organization.

Opportunity Lost

The “glass cliff” describes situations where women are assigned to positions associated with crisis with high risk of failure and criticism (Ryan, Haslam, & Postmes, 2007). Women executives are set up to work under conditions that lead to job dissatisfaction, feelings of disempowerment, and higher risk. Ryan and Haslam (2005) described how women in law firms were given problematic cases and hard-to-win seats compared to men. Other research indicates how women are only considered for leadership positions in companies that are facing financial difficulty and more studies showed how business leaders were more unlikely to pick females to head their companies (Long, 2014). A study by Keziah (2012), for example, showed that male recruiters favored male candidates for low-risk positions. Female recruiters consistently favored a female candidate, with this preference being more marked for a high-risk role. Unless companies develop policies and follow practices to tap into the female talent pool and take proactive steps to reverse this brain-drain, the loss of human capital and underutilization of talent can put companies at disadvantage (Hoobler, Lemmon, & Wayne, 2011). This underscores the fact that companies that achieve diversity and manage it well attain better financial results, on average, than other companies. For exampl...