![]() PART ONE

PART ONE![]()

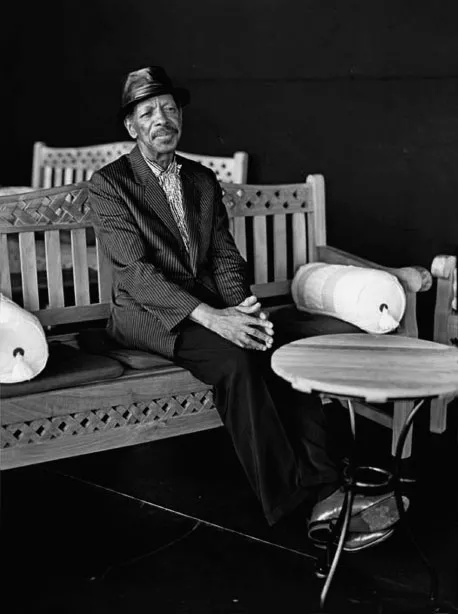

Figure 1.1: Ornette Coleman.

PHOTO COURTESY OF MICHAELA DEISS.

1

Historical Context

Harmolodics is about the relationship between style and process in improvisation. It is also about human rights and issues surrounding equality. Simply put, Harmolodics respects every single voice in an ensemble, without creating a preference or elevated function for any one instrument. This is consistent with the founding principles of Jazz, expressed in the music of Louis Armstrong and King Oliver. Of Armstrong and Oliver, Ornette says, “they had something to back them up, and that’s what we call Sound.” When Ornette said that to me, it brought to my mind the opening sentence from the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was God.” Sound is the fundamental principle of music, and Ornette is saying that the origins of Jazz contain that funda mental principle—Sound. Sound is a term that Ornette often uses idiosyncratically. In addition to the textbook definition of Sound, Ornette’s approach to the topic includes emotion, source, human connection—the metaphysical origins from which his music emerges.

Harmolodics is also the science, one might say, of exploring the basic premise for improvisation: the empowerment of each human voice within the ensemble, or, more broadly, within society. Consequently, it makes complete sense that this approach to music would emerge and develop in parallel with the Civil Rights Movement.

Ornette Coleman was born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1930. When Ornette was nineteen years old, President Truman signed an executive order to insure “equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed services.” Sadly, Truman rescinded the order within one year, declaring that the order had accomplished its goals. Many of us alive today romantically imagine the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement as the moment in 1955 when Rosa Parks famously refused to “go to the back of the bus.” But the roots of the Civil Rights Movement go back much further, pre-dating the Emancipation Proclamation of 1861. And Jazz has deep roots in field hollers and spirituals, born out of slave culture, especially in the Deep South. Certainly it is true that the struggle for freedom for black Americans gained new, increased urgency shortly after the Second World War, and continues to the present day.

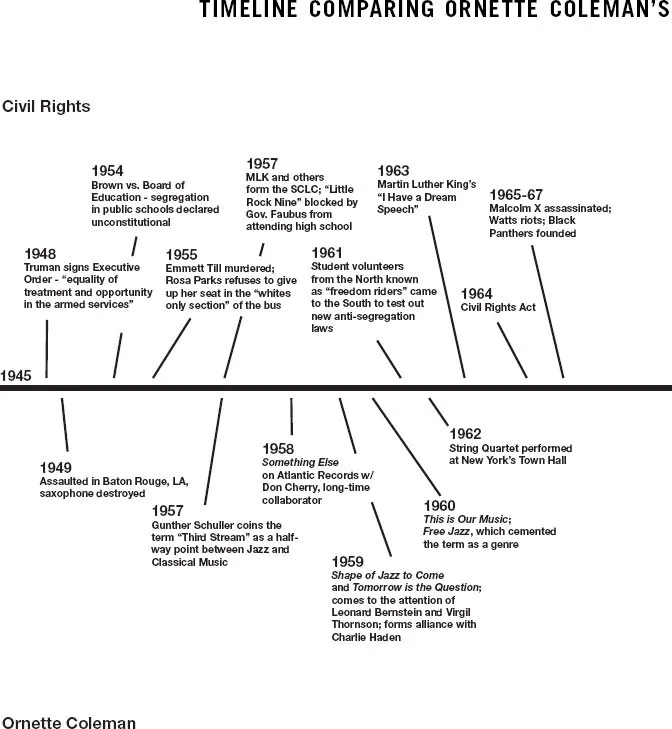

In the timeline above one can see remarkable simultaneities between Ornette’s career and the progress of the march for civil rights. Around the same time that Ornette was being publicly recognized by musicians and critics such as the white composers Leonard Bernstein, Gunther Schuller, and Virgil Thompson, Brown v. Board of Education was decided and Rosa Parks became national news.

It is too much to say that the relationship between these events and Ornette’s music was one of cause and effect. It is clear, however, that Ornette’s music and thinking were closely tied to the transformational events of his day. Observe, for example, how the titles of his albums seem to underscore huge political upheaval, as in Change of the Century (1960); and the power and significance of black American Music, This is Our Music (1959). It is particularly striking that in the same year that the genre-coining album Free Jazz was released—1960—freedom fighters from the North were going south to push for the enforcement of anti-segregation laws. Within mere months of the assassinations of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, Ornette released his album Crisis, with a dramatic picture of the Bill of Rights in flames on its cover.

Figure 1.2: Artist Frederick Brown, Ornette Coleman, and President Bill Clinton, next to Brown’s portrait of Ornette.

PHOTO COURTESY OF MICHAELA DEISS.

Ornette’s musical commentary on civil rights continued throughout the remainder of his life, into the twenty-first century. It was within a two-year time frame that Ornette won a Pulitzer Prize in Music, a Grammy Award, and the MacArthur Genius Award, and Senator Edward Kennedy introduced the Civil Rights Act of 2008. One cannot shrug these simultaneities off as coincidence, because Ornette Coleman himself frames his approach to music in relation to civil rights and racial justice. “I am not a member of the total human race,” he says, “and I do not know how to become a member.”

Ornette Coleman believed in the value of all Life. As he said to me: “Life. L–I–F–E! Now worms, ants, everything … live like that. So do people. We all change in some form or another. But it’s for the purpose of becoming what we call age, knowledge, and ability. But that only represents two things: Humans and Value. That has something to do with what is called ‘How Valuable You Are.’”

![]()

2

An Introduction to Harmolodics

Harmolodics is about collective improvisation. It posits that equal consideration should be given to each player. Early Jazz uses this very premise for improvisation. The concept of the “extended solo” later, as a feature of Bebop, commenced roughly in the 1940s. The music of King Oliver and Louis Armstrong shows a more collective sensibility—a group articulation of form and melody—than the more hierarchical approach found in later Jazz.

Harmolodics is also about breaking the stranglehold that harmony had on Jazz by the end of the 1950s. American song form and Bebop had confined Jazz to a “head–solos–head” structure, or “composed melody–improvise over the changes–melody.” Harmolodics uses that rubric also, as any of the transcriptions in this volume will show, but the “improvise over the changes” aspect is replaced with “improvise over the ethos of the composition.” This could mean changing the groove, that is, breaking away from the constraints of 4/4 time, or even slowing down or speeding up. It definitely implies moving beyond the changes into what has now become known as “Free Jazz,” allowing for virtually unlimited possibilities of transposition and fragmentation/extension.

Ornette and all of the players analysed in this book have some basic strategies for solo improvisation that could be codified as “Harmolodic approaches,” namely:

• purposeful use of range to organize the structure of an improvisation

• references to keys within and without the home key of the composition during the improvisation

• the artful manipulation of phrase length

• a balance between “inside” and “outside”

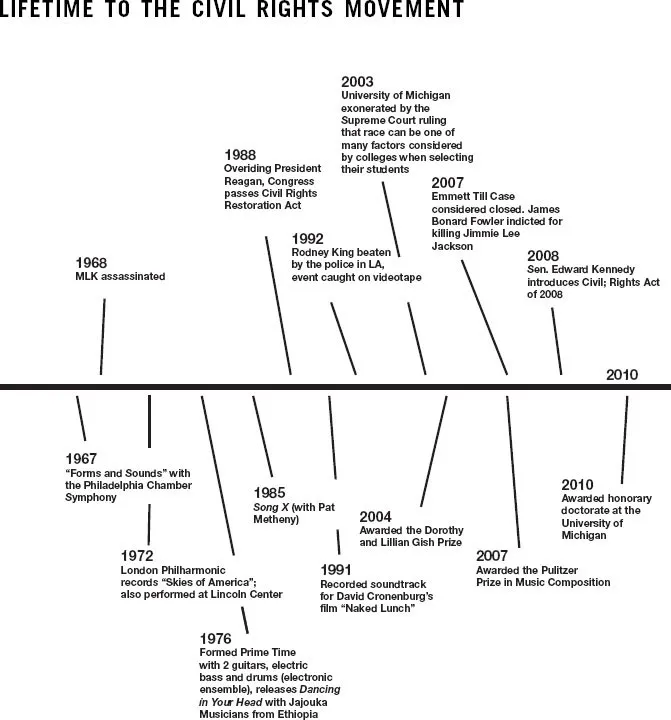

Figure 2.1: Ornette Coleman.

PHOTO COURTESY OF MICHAELA DEISS.

• a playful use of folksong-like characteristics, to wit, longer note values, antecedent–consequent phrasing, strong references to the “home key” or “home keys”

• the extrapolation of key centers stated or implied by the head

• the strategic and balanced play between harmonic and rhythmic tension and simplicity

• detailed listening and flexibility by the bandmates to create large-scale structures

• the use of timbre as an expressive tool

• the use of Pop groove references within a Free Jazz composition

• clear reference to Blues modality and phrasing.

These comprise the building blocks of Harmolodics, pure and simple: but they must be intelligently executed.

![]()

3

Transposition and Harmolodics

Ornette Coleman had a very specific way of talking about transposition. In our interview (Chapter 6), he emphasized the equality of all tones: “We have seven notes to each key,” he said. “We only have twelve keys, but they are all coming from the same notes. That means you have C natural on the violin and C natural on the trumpet; you have two different C’s…. But the people that are trying to improvise something—they can’t use both of those C’s for the same purpose. They have to find which one is going to yield to the other C. But it won’t work that way.”

It is very important to understand exactly what Ornette Coleman meant here. He meant that a C on a violin sounds as “C concert pitch,” and a written C on a trumpet sounds as “B♭ concert pitch” due to transposition, and because the trumpet is a “B♭ instrument.”

Later in the interview, Ornette said: “All the keys have the same resolution of any recipe used for any idea. C to F♯ is a flat fifth [enharmonically speaking]. But F♯ to C♯ is a perfect fifth. Well, that means that the C and C♯ are dominating the F♯. And it’s true! I learned that about ten years ago or more. That is why I don’t worry about the keys or the changes.” In other words, C can become the dominant of F, C♯ can become the dominant of F♯. Thus Ornette’s thinking does agree in part with Western European traditional harmony.

Notes can have the same names, but nevertheless sound as different tones. In concert pitch, a C on a trumpet is not going to sound like a C on a piano. As Ornette says, they “can’t be used for the same purpose.” However, this nomenclature allows a huge opening for Jazz and all music—the possibility that one no longer has to adhere rigorously to prescribed keys or changes. But, how does one proceed without such constraints? My analyses of the transcriptions in this volume will help elucidate the systematic use of such principles. Harmolodics is not anarchy. It is not a matter of “play whatever you want, there are no wrong notes.” R...