![]()

1

SUSTAINABLE WETLANDS: AN ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE

Kerry Turner

Introduction

The analysis and case study examples in this book have been brought together to address five important questions concerning wetland ecosystems:

1 What is the current status of the world’s wetlands (with special focus on OECD countries)?

2 If wetland losses are significant, why should society be concerned? Are wetlands valuable, and can their worth be quantified in monetary terms?

3 Is it the case that valuable wetland resources are not being managed properly (that is, optimally, in economic terms), resulting in socially inefficient resource use?

4 If this social inefficiency exists, what is the source of the problem?

5 What can/should be done about the problem?

Most of the book focuses on temperate wetlands, although the general principles discussed are also applicable to tropical wetlands in developing countries. Nevertheless, there is a general lack of available information in the literature concerning tropical wetlands and their valuation (Barbier, 1989; Turner, 1990).

The case studies presented in the book demonstrate that wetlands are very valuable, multifunctional environmental resources. Despite this fact, they have been disappearing at an alarming rate all over the globe. All wetlands are under threat from a variety of local or regional human activities. Now the perilous state of coastal wetlands is being even further threatened by one of the consequences of global warming. If the “greenhouse effect” actually operates as predicted, mean sea levels may rise as much as one metre by the year 2100 (Thomas, 1986).

Such an accelerated increase in average sea levels would have serious impacts on the worldwide distribution of coastal wetlands. Salt, brackish and freshwater marshes in temperate zones, and mangroves and other swamps in tropical zones would be inundated or eroded (Turner, Kelly and Kay, 1990). Some wetlands would be able to migrate inland, but others would be prevented from doing so by coastal engineering structures. Although many wetlands have kept pace naturally with historic sea level rises, due to sediment entrapment and peat formation, the vertical accretion of wetlands has never been observed to occur at rates comparable to those projected for sea level rise in the next century.

The threat of global warming simply reinforces the fact that policy-makers need to formulate and implement a much more sustainable management approach to wetland stocks. Wetlands are, of course, not the only environmental resources that require “better” management, and the recent “sustainability” debate has been concerned with the development of entire economic systems and their ecological foundations. A few words about this debate are in order to set the stage for what follows (Pearce and Turner, 1990; Turner, 1988a; Pezzey, 1989; and Pearce, Markandya and Barbier, 1989).

Sustainable economic development

During the past decade, the focus of the environmental debate has shifted from the need for absolute limits on growth toward the need for more sophisticated, relative limits.

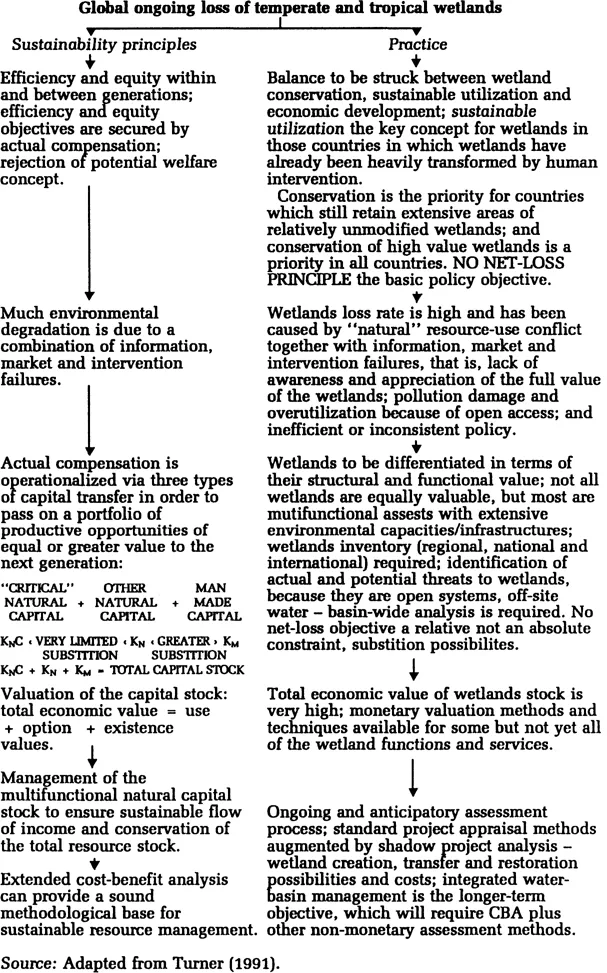

Figure 1.1 illustrates the basic model of sustainable economic development (SED) that has emerged since the publication of the influential report by the Brundtland Commission, Our Common Future (WCED, 1987).

The Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Economists are familiar with this as the Pareto criterion for establishing an increase in the overall welfare of society. In practical cost-benefit analysis (CBA), the Pareto criterion is modified, in order to reduce its restrictiveness, to incorporate the idea of “potential compensation”. Thus, there is an increase in potential welfare if those who gain from a policy or project could, hypothetically, compensate those who lose. Although the idea of potential welfare is consistent with the criterion of economic efficiency, it is not consistent with the criterion of equity. An equity-orientated approach would require that gainers must actually compensate losers.

Figure 1.1: Principles and practice of sustainable development in the wetlands context

Most definitions of sustainable development accept the equity principle, in the sense that they require a non-declining (and unimpaired) stock of capital assets (in value terms) to be transferred from one generation to the next. According to this analysis, the aggregate stock is made up of three components: “critical” natural capital (KNC), “other” natural capital (KN) and man-made capital (KM). The KNC category is composed of vitally important ecosystems and processes, which by definition are of very high value.

If future generations are not to be made worse off by present-day activities, they require the same potential economic opportunities for improving their welfare as the current generation enjoys. The portfolio of capital assets must therefore be managed in such a way as to preserve this potential. The three elements of total capital stock should be viewed as part of a continuum, with each element being more or less substitutable for the other. Exactly which natural capital is considered critical for present and future generations, and the extent to which different types of natural and man-made capital may substitute for each other in years to come, is somewhat uncertain. But there is a strong policy message in this uncertainty, which says that when dealing with potentially essential resources that may be irreplaceable, decision-makers should adopt risk-averse strategies and favour conservation over development.

This model of sustainable development requires that the three types of capital stock eventually be reduced to a common index for comparative purposes. A monetary unit is the yardstick that is usually selected for this purpose. Therefore, the question of valuation becomes very important. As we will see later, the valuation problem is particularly difficult in the case of“critical” natural capital.

Once the different types of capital have been valued, the scene is set for management action to maximize efficiency in the use of that capital, and to fulfill the intergenerational equity objective. Extended cost-benefit analysis can provide an appropriate framework in which these management decisions can be taken.

Wetlands and sustainable development

We now examine the position of wetlands in this sustainable economic development model. The “Practice” column of figure

1. 1 illustrates the state of the wetland situation under each of the critical natural capital, other natural capital and man-made capital headings discussed above. A few generalizations will clarify Figure 1.1 and set the scene for the more detailed discussion in succeeding chapters. In the case of temperate wetlands in developed countries, where wetland stocks have already been heavily transformed by human intervention, sustainable utilization should be the key management concept.

Sustainable utilization should also be the main priority in managing tropical wetlands in developing countries. The control of population growth, as well as the expansion of economic opportunities available to the current generation (given their relative poverty) are essential elements of such a strategy. As has already occurred in developed countries, wetlands stocks in developing nations should be routinely tapped to increase the flows of income from these assets. However, unlike in developed countries, care should be taken to avoid overexploiting these resources in the development process. In other words, maximum sustainable income flows should be the objective.

On the other hand, conservation (that is, management of the rate of change in ecosystems) should be the priority for those developed countries which still retain extensive areas of relatively unmodified wetlands. Conservation of “high- value” temperate wetlands should also be a priority in all countries, both developed and undeveloped. Conservation of “high-value” wetlands is typically an international - not just a national - priority, and may require international compensatory mechanisms when applied to developing nations, for example debt for nature swaps.

As noted earlier, practical experience indicates that wetland losses are continuing at alarming rates in many parts of the world. The reasons for these losses typically involve a combination of market- and policy-intervention failures. A review of these failures in some countries comprises the major focus of this book.

Whichever management strategy is chosen, it will not be costless, so it is very important that wetlands be correctly valued. Overall, the most appropriate type of management system (including the option of converting wetlands with or without compensation) will depend on such factors as: biological conservation needs; the wetland functions and services re-quiring protection, and their total economic value; regional economic opportunities; adjacent land-use patterns; as well as some factors specifically relevant to developing economies, such as the subsistence needs of local people, and the availability of environmentally-sensitive aid flows (Turner, 1989).

We now return to the five questions posed earlier and begin with a summary of available information about wetland losses.

Wetland losses

Wetland ecosystems account for about six per cent of the global land area and are considered by many authorities to be among the most threatened of all environmental resources. During the twentieth century, wetland loss rates have generally been very high. Both the physical extent of wetlands and their quality (in terms of species diversity, etc.) have declined. Most of the physical losses have been due to the conversion of wetlands to other land uses, for example industrial, agricultural and residential. But qualitative degradations - for example chemical and biological - have also occurred, with more subtle, complex and longer-term results. The risks of degradation have been increased by the “open-system” nature of wetland resources. This has made wetlands especially prone to damage caused by activities located a considerable distance away from the wetland site, but still within the drainage basin.

Although areas such as North America and Australia retain significant and relatively pristine wetland stocks, these stocks are nothing like as large as they once were. In most of Europe, the amount of wetlands acreage that remains is only a fraction of the original stock, and is often close to, or below, critical threshold levels. Precise loss estimates on a national basis are not generally available. Several OECD countries did implement policy changes, beginning in the mid-1970s, designed to slow down wetland conversion but the impact of these policy changes has not been sufficiently monitored for a clear judgement to be made about their success. Nevertheless, there is a strong probability that wetland losses continue to be high in many OECD economies.

On a global scale, the extensive tropical wetland resources in developing economies are also undergoing changes, due to improved access to wetland zones; to the pressures of population growth; and to economic development generally. Extensive areas of tropical wetland are being lost, either as a direct result of conversion to intensive agriculture, aquaculture or industrial use, or through more gradual qualitative changes caused by hydrological perturbation, pollution and unsustainable levels of grazing and fishing activities.

Goodland and Ledec (1989) have remarked that, until two or three decades ago, a large proportion of the world’s wildlands (including wetlands) were protected by their remoteness, their vastness and their marginal usefulness for agriculture, or other economic activities. The last thirty years or so, however, have witnessed the rapid conversions of wetlands in all developing countries.

Mangrove swamps, for example, are rapidly disappearing throughout Asia and Africa, because of land reclamation, fishpond construction, mining and waste disposal. In the Philippines alone, some 300 000 ha (67 per cent) of the national mangrove stock has been lost over the period 1920-80. Other wetland types have suffered equally rapid losses. In Nigeria, the flood plains of the Hadejia River have been significantly reduced as a result of dam construction. Qualitative degradation is also a serious problem - the majority of coastal wetlands in Brazil have been degraded by pollution.

Each of the case studies examined in this book - USA, UK, France and Spain - contain considerable evidence to support the presumption that wetland losses are also occurring in developed nations.

The next important question to pose...