![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Defining the problem

Any examination of long-standing refugee populations in the developing world should begin with a definition of the nature and causes of protracted refugee situations.1 Such a definition has remained elusive in recent years and this may have frustrated efforts to formulate effective policy responses. A more detailed understanding of the global scope and growing importance of the problem is also important as a basis for understanding the commonalities and differences of various protracted refugee situations, both contemporary and historical. The objective of this chapter is to provide analytical tools with which to examine protracted refugee situations.

Towards a working definition

UNHCR defines protracted refugee situation as,

one in which refugees find themselves in a long-lasting and intractable state of limbo. Their lives may not be at risk, but their basic rights and essential economic, social and psychological needs remain unfulfilled after years in exile. A refugee in this situation is often unable to break free from enforced reliance on external assistance.2

In identifying the major protracted refugee situations in the world, UNHCR uses the ‘crude measure of refugee populations of 25,000 persons or more who have been in exile for five or more years in developing countries’.3

This definition reinforces the popular image of protracted refugee situations as involving static, unchanging and passive populations and groups of refugees that are ‘warehoused’ in identified camps. In view of UNHCR’s humanitarian mandate, and given the prevalence of encampment policies in the developing world, it should not be surprising that such situations have been the focus of UNHCR’s engagement in the issue of protracted refugee situations. The UNHCR definition does not, however, fully encompass the realities of such situations. Far from being passive, recent cases illustrate how refugee populations have been engaged in identifying their own solutions, either through political and military activities in their countries of origin or through seeking means for onward migration to the West. In addition, evidence from Africa and Asia demonstrates that while total population numbers in protracted refugee situations remain relatively stable over time, there are, in fact, often significant changes within the membership of that population. For example, while the total number of Burundian refugees in Tanzania was relatively stable in recent years, at just under 500,000, there have been significant numbers of both new arrivals and repatriations to Burundi in recent years.

A more effective definition of protracted refugee situations would include not only the humanitarian elements proposed by UNHCR, but also a wider understanding of the political and strategic aspects of long-term refugee problems. Secondly, a definition should reflect the fact that protracted refugee situations also include chronic, unresolved and recurring refugee problems, not only static refugee populations. Thirdly, an effective definition must recognise that countries of origin, host countries and the international donor community are all implicated in long-term refugee situations.

Protracted refugee situations involve large refugee populations that are long standing, chronic or recurring. These populations are not static, often increasing and decreasing over time, and undergoing changes in composition. They are typically, but not necessarily, concentrated in a specific geographical area, but may include camp-based and urban refugee populations.4 The nature of a chronic refugee situation will be influenced both by conditions in the refugees’ country of origin and the responses and conditions in the host country. Refugees of one nationality in different host countries will result in different protracted refugee situations. For example, the circumstances of long-term Sudanese refugees in Uganda are different from those of Sudanese refugees in any of the other seven African host countries. In this way, one country may produce several protracted refugee situations.

Given the varied political causes and consequences of protracted refugee situations, it is difficult to lay down precise parameters of what size refugee population and how many years in exile constitute such a situation. Politically, the identification of a protracted refugee problem is, to a certain extent, the result of perception. If a refugee population is seen to have been in existence for a significant period of time without the prospect of resolution, then it may be termed a protracted refugee situation.

Trends in protracted refugee situations

Long-term refugee scenarios are a growing challenge. Not only are their consequences being more keenly felt by host states and regions of origin, but their total number has increased dramatically in the past decade. More significantly, protracted refugee problems now account for the vast majority of the global refugee population, demonstrating the importance, scale and global significance of the issue.

In the early 1990s, a number of long-standing refugee populations that had been displaced as a result of proxy wars in the developing world went home. In Southern Africa, huge numbers of Mozambicans, Namibians and others repatriated. In mainland southeast Asia, the Cambodians in exile in Thailand returned home and Vietnamese and Laotians were also repatriated. With the conclusion of conflicts in Central America, the vast majority of displaced Nicaraguans, Guatemalans and Salvadorans returned to their home countries. According to UNHCR, in 1993, in the midst of the resolution of these conflicts, there were 27 protracted refugee situations, with a total population of 7.9 million refugees.

While these Cold War conflicts were being resolved, and as refugee populations were being repatriated, new intra-state conflicts emerged and resulted in massive new refugee flows during the 1990s. Conflict and state collapse in Somalia, the African Great Lakes, Liberia and Sierra Leone generated millions of refugees. Millions more refugees were displaced as a consequence of ethnic and civil conflict in Iraq, the Balkans, the Caucasus and Central Asia. The global refugee population mushroomed in the early 1990s, and there was a pressing need to respond to the challenges of simultaneous mass influxes in many regions.

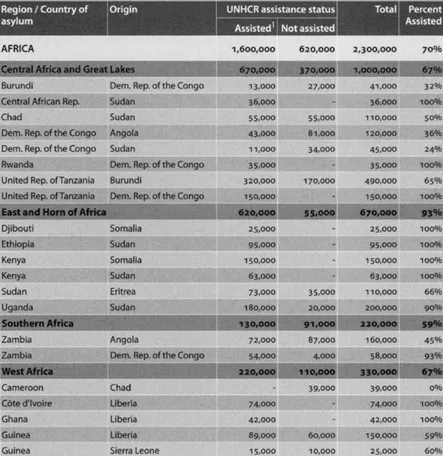

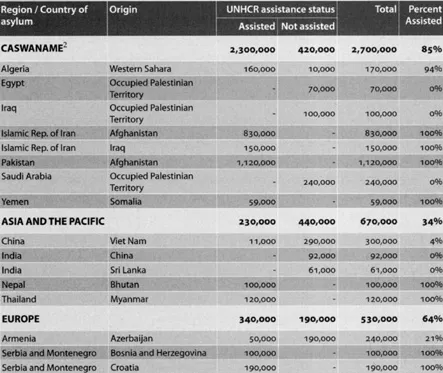

Ten years later, many of these conflicts and refugee situations remain unresolved. As a result, the number of long-term refugee populations is greater now than at the end of the Cold War. In 2003, there were 38 cases of refugee populations greater than 25,000 being in exile for five or more years, with a total protracted refugee population of 6.2m (see Table 1.1). While there are fewer long-staying refugees today, the number of chronic situations has greatly increased. In addition, refugees are spending longer periods of time in exile. It is estimated that ‘the average of major refugee situations, protracted or not, has increased from nine years in 1993 to 17 years at the end of 2003’.5 With a global refugee population of over 16.3m at the end of 1993, 48% of the world’s refugees had been in exile for five or more years. At the end of 2003, the global refugee population stood at 9.6m, and over 64% of this number were in protracted refugee situations, usually in the most volatile regions.

It is also important to note that the percentage of the world’s refugees in extended exile would increase significantly if the definition included groups of refugees smaller than 25,000. For example, such a definition would exclude the thousands of Liberian refugees in Ghana and Sierra Leone; Somalis in Djibouti, Eritrea and Tanzania; Burundians in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); and Burmese in Malaysia, to list but a few. It would also be a larger figure if the calculation included elements of refugee population for whom a solution has been found for the majority of refugees. For example, the vast majority of some 200,000 Rohingya refugees from Myanmar who fled to Bangladesh in the early 1990s later repatriated. There remains, however, a group of some 20,000 Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh who continue to resist return. Such ‘residual caseloads’ constitute a considerable percentage of protracted refugee situations, but typically fall below the threshold of 25,000. However, as the case of the Rohingyas in Bangladesh, Rwandans in Uganda or Ghanaians in Togo clearly illustrate, these residual groups are among the most difficult to resolve. While the crude measure of 25,000 refugees in exile for five years should not be used as a basis for excluding other groups, it does provide a useful point of departure.

East and West Africa, South and Southeast Asia, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Middle East are all plagued with chronic refugee problems where refugees remain uprooted, unprotected and with no immediate prospect of a solution to their plight. Sub-Saharan Africa hosts the largest number of protracted refugee situations in one region: 22, involving a total of 2.3m refugees. The most important host countries on the continent are Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia and Guinea. In contrast, the geographical area encompassing Central Asia, South West Asia, North Africa and the Middle East hosts eight major long-term populations, accounting for 2.7m refugees. The overwhelming majority are the Afghans in Pakistan and Iran, who total nearly 2m at the end of 2003. In Asia, there exist five protracted situations: a total of 670,000 refugees in China, Thailand, India and Nepal. In Europe, there were three major protracted populations, totalling 530,000 refugees, primarily in the Balkans and Armenia.

Causes of protracted refugee situations

As this overview illustrates, protracted refugee populations originate from the very states whose instability lies at the heart of chronic regional insecurity. The bulk of refugees in these regions – Somalis, Sudanese, Burundians, Liberians, Iraqis, Afghans and Burmese – come from countries where conflict and persecution have persisted for years. It is essential to recognise that protracted refugee situations have political causes, and therefore require more than humanitarian solutions. As argued by UNHCR,

protracted refugee situations stem from political impasses. They are not inevitable, but are rather the result of political action and inaction, both in the country of origin (the persecution and violence that led to flight) and in the country of asylum. They endure because of ongoing problems in the country of origin, and stagnate and become protracted as a result of responses to refugee inflows, typically involving restrictions on refugee movement and employment possibilities, and confinement to camps.7

Protracted refugee problems are caused largely by both a lack of engagement by a range of peace and security actors in the conflict or human-rights violations in the country of origin, and a lack of donor government involvement with the host country. Failure to address the situation in the country of origin means that the refugee cannot return home. Failure to engage with the host country reinforces the perception of refugees as a burden and a security concern, which leads to encampment and a lack of local solutions. As a result of these failures, humanitarian agencies, such as UNHCR, are left to compensate for the inaction or failures of the major powers and the peace and security organs of the UN system.

To give one example, the extended presence of Somali refugees in East Africa and the Horn is the direct result of the consequences of failed intervention by the US and the UN in Somalia in the early 1990s and the inability or unwillingness of the major donor countries to engage in the task of rebuilding a failed state. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees have been exiled within the region for over a decade, with humanitarian agencies like UNHCR and the World Food Programme (WFP) responsible for their care and maintenance as a result of increasingly restrictive host state policy.

In a similar way, failures on the part of the UN Security Council and regional organisations, such as the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Association of Southeast Asian States (ASEAN) and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), to consolidate peace can lead to resurgence of conflict and displacement, leading to a recurrence of protracted refugee situations. For example, the return of Liberians from neighbouring West African states in the aftermath of the 1997 elections in Liberia was not sustainable. A renewal of conflict in late 1999 and early 2000 led not only to a suspension of repatriation of Liberian refugees from Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire and other states in the region, but led to a massive new refugee exodus. Following the departure into exile of Charles Taylor in 2003, there has been a renewed emphasis on return for the hundreds of thousands of Liberian refugees in the region, and large-scale facilitated repatriation began in late 2004. It does not, however, appear as though the lessons of the late 1990s have been learned. Donor support for demobilisation and reintegration of Liberian combatants has been limited, and there is rising concern over the possibility of a renewal of conflict, especially among former combatants who are again being recruited into rival factions.

The primary causes of protracted refugee situations are to be found in the failure of major powers, including the US and the EU, to engage in countries of origin and the failure to consolidate peace agreements. These examples also demonstrate how humanitarian programmes have to be underpinned by sustained political and security measures if they are to result in lasting solutions for refugees. Assistance to long-term refugee populations through humanitarian agencies is no substitute for sustained political and strategic action. More generally, the international donor community cannot expect the humanitarian agencies to respond to, let alone resolve, long-term refugee problems without the sustained engagement of the peace and security and development agencies, including the UN Security Council, the UN Development Programme, the World Bank and related international, regional and national agencies.

Declining donor engagement in programmes to support long-standing refugee populations in host countries has also contributed to the rise in long-term refugee populations.8 A marked decrease in financial contributions to assistance and protection programmes for chronic refugee groups has had not only security implications, as refugees and local populations compete for scarce resources, but has also reinforced host state perceptions of refugees as a burden. Host states now argue that the presence of refugees results in additional burdens on the environment, local services, infrastructure and the local economy, and that the international donor community is less willing to share this burden. As a result, host countries are less willing to engage in local solutions to protracted refugee situations, and more likely to contain refugees in isolated camps until a solution may be found outside the host country.

This trend first emerged in the mid-1990s, when UNHCR had budget shortfalls of tens of millions of dollars. These shortfalls were most acutely felt in Africa, where contributions to both development assistance and humanitarian programmes fell throughout the decade. There was also an apparent bias in the allocation of UNHCR’s funding towards refugees in Europe over refugees in Africa. In 1999, it was reported that UNHCR spent about 11 cents per refugee per day in Africa, compared to an average of $1.23 per refugee per day in the Balkans.9 In 2000 and 2001, most UNHCR programmes in Africa were forced to cut their budgets by 10–20%. Successive cut-backs to UNHCR’s programme in Tanzania provide but one example. In 2001, the UNHCR was forced to reduce its budget in Tanzania by some 20%, resulting in the scaling-back of a number of activities.10 In 2002, the UNHCR had to cut $2m from its total budget of $28m. Again, in 2003, UNHCR rep...