Chapter 1

The gastrointestinal tract

A brief introduction to healthy digestion

Christopher F.D. Li Wai Suen and Peter De Cruz

Learning points

- Introduction to the GI tract, including its biological, chemical, and physical methods to digest (break down), move, and absorb nutrients

- A brief introduction to the GI microbiota and immune system, and their association with disease states

Background

The GI system is made up of several organs that work together to carry out its many functions. Main functions of the GI system include:

- Digestion and absorption of food and nutrients

- Regulation of the fluid and electrolyte balance in the body

- Excretion of waste products

The GI system also plays an important role in immune defence. It has multiple mechanisms in place to defend the body against potentially harmful bacteria and viruses that we ingest, and which may cause illness.

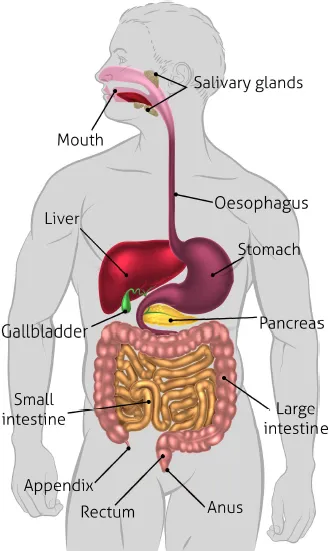

Basic structure and function of the GI system

The GI tract is ‘designed’ in a way that enables its structure to carry out its functions effectively. In its basic structure, the GI tract consists of a long muscular tube that runs from the mouth to the anus and is connected or closely related to other organs such as the pancreas, liver, and spleen (Figure 1.1 and Handout 1.1 provide an overview of the GI system and its functions). The tubular structure of the GI tract carries ingested food from the mouth and, at different points along its tract, food is broken down by the process of digestion. Food is digested (broken down) into small molecules that can then be absorbed so that they can be used by the body for metabolic functions, including the production of energy, cell repair, and growth. Whatever is not absorbed by the GI tract is excreted as waste in the stool.

Figure 1.1 Human gastrointestinal tract

The wall of the GI tract is made up of several layers. Starting from the inside of the GI tract (lumen) and moving out, the layers include:

- The mucosa, that is in direct contact with the content of the lumen.

- The submucosa, a supporting structure that contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves (including the submucosal plexus of Meissner).

- A muscular layer, consisting of an inner circular muscle layer that is surrounded by a longitudinal muscle layer (i.e., one layer of muscle that goes around the tube, surrounded by another layer that runs along the length of the tube). Between these two muscle layers lies the myenteric plexus of Auerbach, a complex of nerves that supplies the muscle layer, and is made up of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves.

- Of note, the stomach also has an additional middle layer of muscle.

- An external wrapping called the ‘serosa’.

To propel food along its length, the GI tract relies on peristalsis, a wave-like contraction created by the coordinated contraction and relaxation of muscles within the wall of the tube. Although the GI tract is essentially tubular in structure, it has several modifications along its length so that it can carry out its functions more effectively. While the oesophagus (‘food pipe’) is a long tube in the shape of a hose, the stomach is saccular in shape, acting as a short-term storage repository where it mixes and churns food with gastric juices.

Sphincters also occur at various points in the GI tract. These circular muscles act as gateways that regulate the passage of food products. By contracting, they stop the flow of content whereas by relaxing, they allow the passage of contents. The pyloric sphincter (or pylorus), for example, is at the exit end of the stomach and regulates passage of food into the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine connected to the stomach).

Blood supply and innervation: general principles

The aorta is the largest artery in the body and runs from the chest to the abdomen; it carries blood to various parts of the body. The aorta gives off branches that supply the GI tract with oxygen-rich blood so that it can carry out its functions. The GI tract can be divided into three territories, which from top to bottom, are supplied by the coeliac artery, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery. Most of the blood from the GI tract drains into the portal vein, which carries nutrients that have been absorbed from the GI tract into the liver where they are processed or redistributed to other organs. From the liver, blood returns to the heart via hepatic veins.

In addition to its blood supply, the GI tract has significant innervation (nerve connections) that enables it to carry out its tasks optimally. The GI tract has its own nervous system termed the ‘enteric nervous system’ (ENS), found within the wall of the GI tract. The ENS is a complex and fascinating system. With more than 500 million neurons (nerve cells), the ENS is often referred to as the ‘second brain’ of the body because of its similarities with the structure and function of the brain [1, 2]. The ENS relies on more than 20 different neurotransmitters to relay information across its complex network. In fact, 95% of the body’s serotonin is found in the ENS and GI tract, reflecting the significance of neural connections [3].

The ENS is responsible for various physiological processes in the GI tract. It controls the motility of the GI tract, regulates the blood flow and movement of fluid across its wall, controls hormone and enzyme secretion from the stomach and pancreas, and regulates the response of the immune system in the GI tract [4].

While the ENS can operate independently, it is also under the influence of the central nervous system (CNS; i.e., brain and spinal cord) via connections from the autonomic nervous system (ANS), comprising the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems [1]. The latter two are akin to the ‘yin and yang’ of the nervous system and can up- or down-regulate the activity of the ENS. In stressful or ‘fight or flight’ situations, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) becomes more active. The end-result is decreased peristalsis in the bowel and blood being diverted away from the GI tract, while at the same time heart rate and blood pressure increase. In contrast, parasympathetic system (PNS) activation enables humans to ‘rest and digest’. See Chapter 5 for a detailed overview of the ENS and the impact of stress on the GI tract.

The communication between the ENS and the CNS is bi-directional, and the pathways involved are referred to as the ‘brain-gut axis’ (BGA; see Chapter 5 for an overview). In other words, in addition to the influence of the brain on digestion and GI function as already mentioned, the ENS also ‘talks’ to the brain. Nerves of the ANS, for example, convey sensation to the brain, when the bowel is distended.

Nutrients

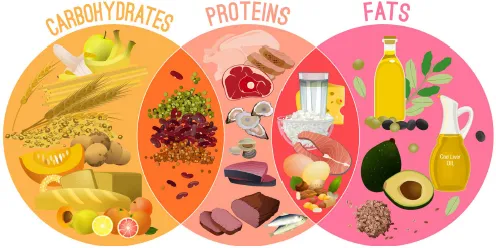

Based on the amount needed by the body, nutrients are classified into two main categories: macronutrients and micronutrients. Macronutrients are needed in large quantities by the body and include carbohydrates, protein, and fat (Figure 1.2). Micronutrients, on the other hand, are only needed in small quantities, and include vitamins and minerals. Most of the carbohydrates, proteins, and fat that we consume are in complex chained forms that cannot be directly absorbed by the GI tract. These need to be digested or broken down into smaller molecules that can then be absorbed.

Figure 1.2 Macronutrients and their common food sources

Digestion: journey along the GI tract

Digestion is the process by which the body breaks down food so that it can be absorbed and used by the body. Digestion itself is made up of two components: mechanical and chemical (or biochemical) digestion. In the former, physical forces, such as chewing and mixing, break down big food pieces into smaller pieces. These smaller pieces have a higher surface area and enable enzymes to work more effectively, hence facilitating chemical digestion.

Digestion of carbohydrates (‘sugars’ such as glucose, starches, fructose, and lactose), proteins (made up of individual blocks called ‘amino acids’), and fat (made up of fatty acids and glycerol) occurs by specific enzymes in complex physiological processes. A brief overview of the digestive process is provided later in the chapter.

The time taken for digestion varies significantly from person to person. It is affected by numerous factors, including gender, and the type and amount of food ingested, as well as the presence of other conditions such as diabetes or disorders of the nervous system. As such, transit times of food in specific areas of the GI tract quoted in this chapter should only be considered as rough estimates.

Mouth (oral cavity) and tongue

Digestion starts in the mouth (Figure 1.3). There, teeth break down large pieces of ingested food into smaller pieces. Various types of teeth are adapted to ...