Chapter 1

Emptiness and Christianity

When one uses the words beauty of holiness, one can call this kind of expressing the holy: “beauty of emptiness.” This emptiness is not an emptiness by privation, but it is an emptiness by inspiration. It’s not an emptiness where we feel empty, but it is an emptiness where we feel that the empty space is filled with the presence of that which cannot be expressed in any finite form.1

Emptiness within Christianity

The Church of the Light (1989), like the Chapel of Notre Dame-de-Haut (1954), positions the altar at the lowest point of the chapel, which symbolizes, in the words of Reverand Noboru Karukome of the church, “Jesus Christ who came down to the lowest of all.” 2 While this treatment is symptomatic of the post-war disenchantment of humanity based on the tragic end of unconstrained technology, it gives rise to the formation of the sense of oneness between the congregation and the altar. Spatial emptiness of the church further strengthens this oneness, an emptiness emerging from its monolithic construction and the astounding stripping of images, icons, and figures from the body of the church. If one puts aside for a moment the crux of the empty cross, which integrates the iconic referential value with the corporeal phenomenal thickness of light, the church appears certainly restrained, or even anti-figurative.

The stress on empty space in the Church of the Light, a church belonging to the United Church of Christ in Japan, which was founded in 1942,3 may be explained by the minimalistic and ascetic tradition of Christianity—including Protestantism. The idea of reductive spatial emptiness in the history of Christianity can be traced back to ancient Judaism. The self-definition of God in a tautological phrase of “I AM WHO I AM” as well as His command not to make “a carved image or any likeness of anything in heaven above or on earth beneath or in the waters under the earth,”4 for fear of falling to idolatry, demanded emptiness in the space of worship.5

The ideal of emptiness, though never articulated as such, underlay the iconoclastic discourse of the eighth-century Byzantine Empire. The iconoclasts’ arguments depended upon the authority of the Old Testament commandment against making images in reverence of God for fear of replacing the invisible God with idolatrous images of gentile gods and goddesses. This iconoclastic argument was further supported by New Testament passages, such as “No one has ever seen God.” 6 Paul the Apostle’s lamentation on the exchange of the invisible and immortal God “for images that looked like mortal human beings, birds, four-footed animals, and reptiles,” a replacement of the Creator with created things, further supported this iconoclastic perspective.7 According to this standpoint, God—the invisible, incorporeal, uncircumscribable Supreme Being—should not be depicted in any tangible material form. The iconoclasts believed such depiction not only distorts and humanizes the divine features of the Supreme Being, but also leads one astray through the seductive, and even erotic, beauty of the image.8

Representation of Jesus Christ, the Son of the Supreme Being, became a critical issue between iconoclasts and iconophiles. The iconoclasts saw the doctrine of incarnation as insubstantial evidence for the creation of images. Any image that depicted Jesus with a physiognomic resemblance to human beings was seen to invite a heretical definition of Jesus as strictly human, not divine. The image, they believed, misconstrued the hypostatic unity of Jesus between the human and the divine. For iconoclasts, the humanity of Jesus was absorbed by, or sublimated into, his divinity once his glorified resurrection was accomplished. Of course, this position was criticized by the opponents of iconoclasm as failing to see the mystery of the incarnation, and as falling into the Nestorian heresy of disjoining the consubstantial state of Christ into the human and the divine.9

Entering into the period of the Reformation, iconoclasm was an attitude generally shared by the Protestant faith, although it would be simplistic to present Protestantism as fundamentally opposed to representational art.10 Reformists including Martin Luther (1483–1546) and Jean Calvin (1509–1564) implicitly supported iconoclastic measures by regarding the issue of images as being subaltern to one’s faith in God. Still, they did not reject the didactic and propagandistic role of images for Protestantism especially during the early moments of the revolution. The famous argument by Luther—calling for the destruction of images merely corroborated superstitious and puerile beliefs in the power of images and indicated a shallowness of faith—rendered marginal the spiritual significance of images compared with the primacy of the Word.11 Luther differentiated his position from Protestant iconoclasts such as Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt (1486–1541) by promulgating the principle of liberty granted to man through the grace of God, which set the adoption of images to be a matter of choice through free will. Even then, however, he did not condemn those who destroyed idolatrous paintings and statues “in an orderly fashion” and “by duly constituted authority,” suggesting less his own form of iconoclasm than a disdain for the violence led by mob psychology.12 In contrast, Karlstadt, Luther’s professorial colleague at the university in Wittenberg and a zealous rival on the issue of Protestant iconoclasm, disapproved of the Orthodox position that what is venerated is not the depicted image itself, but the prototype it represents.13 Partly fearful of his own susceptibility to the idolatrous power of images, he maintained “the total abolition of statuary and figurative paintings in the churches.” 14 Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) also opposed the potentially fetishistic idolatry by cataloguing the manifold cultic acts evident in public devotion, acts that suggested a belief in images themselves as having the power of forgiving sins and of leading the devotees to salvation.15

Erwin Panofsky’s (1892–1968) insights into the relationship between Protestant faith and art during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe are notable for observing the influence of the Protestant iconoclastic tendency on the concept of spatial emptiness. Based on a territorial common ground “more or less coextensive with that of the Germanic tongue,” and hyperborean spiritual common ground, Panofsky cautiously elucidated the intrinsic affinities between Protestant faith and Protestant art: first, “individualism in artistic, intellectual and spiritual matters,” which balances “regimentation in the political sphere”; and, second, “quietism or introspectiveness based on the insurmountable feeling that the soul is not at home in the body.” 16 These two conditions promoted individual interpretations of the Bible and the creations of prints for personal veneration, rather than paintings and sculptures in their grandiose richness and frames. In addition, this quietism or introspectiveness gave rise to what Panofsky called the “eloquence of silence” found in the late works of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) (Figure 1.1), “particularly when the stories told in the Old Testament are rendered.” 17 This quality of silence and tranquility emerged from the subdued monochromatic background combined with suppressed acts of the depicted figures. According to Panofsky, one’s perception of these kinds of works leads to personal absorption, rather than ecstasy in unison with the transcendental power emanating from images of Jesus Christ and the saints. The fundamental alteration of the relationship between God and the human being that is evident in the transition from the public realm of icon worship to the private realm of sereneness contributes, if not directly, to the idea of sacred emptiness. This transition is, at the very least, conducive to the emergence of the church in “eloquence of silence,” purged of paintings, sculptures, and other potentially clamorous objects, while confirming the primacy of the Word to be sonorous in the silence. It was this thrust towards silence that drove Protestant iconoclasts to demolish stained glass windows, paintings, and sculptures from Catholic churches, while creating what Paul Tillich (1886–1965), a prominent Protestant theologian, lamented as “ugly emptiness” and “simple emptiness, often painfully noticeable.”18

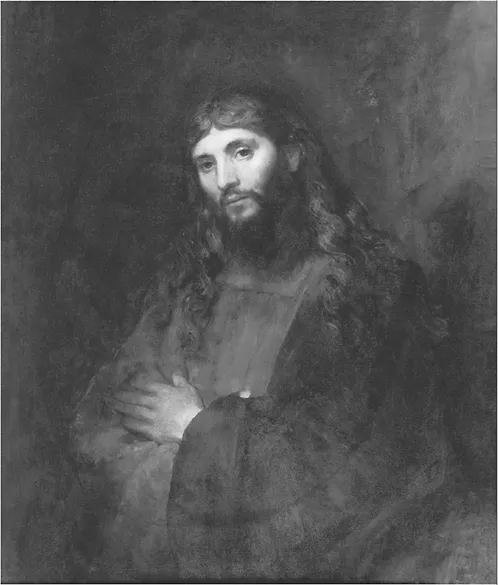

1.1 Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606–1669, Christ with Arms Folded, ca.1657–1661

Oil on canvas, 43 × 35½ inches, 1937, The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, photograph by Joseph Levy

In twentieth century, emptiness was given two theological interpretations by Tillich. First, the spatial emptiness of Christian architecture reflects the atheistic condition of the century. Tillich further claimed the universal communicability of the emptiness as the honest expression of the shared experience during the century, being a period of atheism stained by world wars, fascist and imperial regimes, and the genocide of millions. He considered the removal of images and sculptures from the church to be symbolic of a God who disappeared from human sight. The subsequent effect of emptiness, as Tillich maintained, represented the infinite distance between the withdrawn God and the man left almost severed from His grace. Emptiness viewed on this theological horizon carried with it the universal efficacy of the collective and painful experience of the twentieth century. For Tillich, who saw honesty as a condition for a new spiritual renaissance, emptiness is filled with the atheism of the absent God, and a desire for his return to “disappoint those atheists who believe that he has confirmed their atheism by his withdrawal.” 19 Emptiness in this case is imbued with anticipation, a hopeful “ ‘waiting’ for the return of the hidden God who has withdrawn and for whom we must wait again.” 20

Secondly, for Tillich, emptiness is a sacred word of God. The molding of emptiness is not a side effect of Protestantism, in Tillich’s words, a “religion of the ear and not of the eye” or the “predominance of the Word over the sacrament,”21 but a unique utterance of God, not recited by the lips of priests, but molded by the hands of architects. Emptiness which seems to result from the drastic removal of figural qualities is not simply an architectural by-product of the Protestant ideal, but as a matter of fact one of the very essences of Protestant theology. He wrote:

The first is the emphasis placed by many Protestants upon the infinite distance between the divine and the human, between God and the world, a distance bridged only by the divine Word. From this follows the ideal of “sacred emptiness,” symbolizing this distance. The Jewish tradition, especially its prophetic line, represents this attitude, which was followed in Islam and partly in Protestantism. The sacred void can be a powerful symbol of the presence of the transcendent God. But this effect is possible only if the architecture shapes the empty space in such a way that the numinous character of the building is manifest. An empty room filled only with benches and a desk for the preacher is like a classroom for religious instruction, far removed from the spiritual function which a church building must have.22

Accordingly, the focus at the moment of creating sacred emptiness is not so much on removing signs, icons, symbols, images, and figures, as on molding an empty space from the very beginning. Just as the Word of the Bible leads worshippers to the divine world of God, so does the empty space. If the empty space fails to be “numinous,” it would then be one o...