eBook - ePub

The Design of Lighting

Peter Tregenza, David Loe

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

The Design of Lighting

Peter Tregenza, David Loe

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This fully updated edition of the successful book The Design of Lighting, provides the lighting knowledge needed by the architect in practice, the interior designer and students of both disciplines.

The new edition offers a clear structure, carefully selected material and linking of lighting with other subjects, in order to provide the reader with a comprehensive and specifically architectural approach to lighting. Features of this new edition include:

-

- technical knowledge of lighting in the context of architectural design;

-

- an emphasis on imagination in architectural light and presentation of the tools necessary in practice for creative design;

-

- additional chapters on the behaviour of light and on the context of design;

-

- a strong emphasis on sustainable design and energy saving, with data and examples;

-

- analyses of actual lighting schemes and references to current standards and design guides;

-

- an up-to-date review of lamp and lighting technology, with recommendations on the choice of equipment;

-

- a revision of the calculation section, with examples and step-by-step instructions, based on recent student feedback about the book.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que The Design of Lighting est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à The Design of Lighting par Peter Tregenza, David Loe en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Architektur et Architektur Allgemein. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Part One

Foundations

1 Observing light

2 Describing light

3 Describing colour

4 Light and vision

5 Lamps and luminaires

6 Sun and sky

7 Models and calculations

8 Measuring light

PART ONE is an outline of the physical ideas underlying lighting design. It begins with a chapter called Observing light which gives some examples of the way that light behaves. Its first purpose is to set down systematically facts you need to know about the behaviour of light at the scale of buildings and towns. Its second purpose is to encourage you, wherever you go, to look at the lighting around you – analyse it, identify the primary sources, observe how people react to the place – and to note your own subjective response to the place.

Seven short chapters follow, each introducing an individual topic. They begin with a vocabulary of specialist words and then describe the units in which light and colour can be measured and specified, the human need for light and how the human eye responds, how light is produced electrically and how natural light behaves, and the nature of calculations in lighting and how light is measured.

1.1

1

Observing light

Composers of music know the sounds that voices and instruments make. They know their physical characteristics, their ranges, how easy or difficult it is to sing or play particular notes; and they understand something of the effect that music can have on people. Similar things could be said of those who work in theatre or who paint, or who write poetry, or practice any other art. Part of the process of learning to be creative is to build up vocabularies of sounds or words or images, whatever the medium is. These become the language with which the artist communicates. The lighting designer’s language is brightness and colour in three-dimensional space; our medium is the physical building. But to share knowledge, to teach and to learn, we use a second language: the written and spoken word. This is the language we use to build up a theoretical framework that supports our designing. And like other artists we give some words a special meaning: examples are ‘brightness’, ‘lightness’, ‘colour’ and ‘space’. They are like ‘melody’, ‘harmony’ and ‘rhythm’ in music.

Such words, though, are meaningless to someone who has not experienced what they describe: the ultimate foundation of creative lighting design is a knowledge of real lamps, real windows and real materials. After that comes the need for words that describe what we observe, then abstract concepts.

This first chapter is, therefore, a guide to observing the visual world. The aim is not to compile a mental library of images, though that might be useful. It is to answer the question ‘What are the rules that govern the behaviour of light?’

Look at the intricate pattern of brightness of the evening sky in the photograph, 1.1, of the Arno in Florence. The patterns of clouds, the range of colours, the continuing change and the sheer scale of the display reveal an amazing complexity. But the distribution of brightness in a room also can be complex. Even a single lamp in a windowless room produces a subtle variation of brightness across the room surfaces – the walls, ceiling and floor. With many lamps the pattern of brightness is elaborate; if there is daylight in the room, the pattern is not only more varied spatially but continually changing.

What happens in the evening sky or in a daylit room is the outcome of a small number of physical principles. For practical purposes these principles can be expressed as simple rules about the interaction of light and materials. Such rules are the foundation of a lighting designer’s knowledge. Knowing them makes it possible to predict how a lighting scheme will work, what it will look like, how much energy it will use. The most important of the rules are systematically set out in the following pages. Use them as a structure to your observations.

1.2

Sunbeams made apparent by falling rain. Direct light from the sun passes through gaps between clouds. Some of it is scattered towards the viewer by raindrops, indicating the location and direction of the beams. Kings Canyon, Central Australia.

Sunbeams made apparent by falling rain. Direct light from the sun passes through gaps between clouds. Some of it is scattered towards the viewer by raindrops, indicating the location and direction of the beams. Kings Canyon, Central Australia.

1 | THE FLOW OF LIGHT |

1.1 | A beam of light is invisible |

Before smoking in cinemas was banned there was a visible beam of light from the projection room window to the screen. But it was not the beam itself that could be seen; it was particles of smoke illuminated by the beam which reflected some of the light towards the viewer. In a modern, air-conditioned cinema the beam cannot be seen. When driving a car at night, the beam from a headlight is only visible if the air is misty. On a clear night all that can be seen are the surfaces on which the light falls.

1.2 | Scattering reduces the intensity of a beam and creates a field of diffuse light |

In a large smoky cinema the screen is less bright than it would be in a smoke-free room because some of the beam’s energy has been absorbed and scattered by soot particles.

In the earth’s atmosphere light is scattered out of the sun’s beam. The scattering is not uniform. Gas molecules scatter the blue part of the spectrum much more than the red. Water droplets reflect and refract light at angles that depend on their size. Sometimes we see this as a rainbow. Carbon particles and other pollutants reflect and absorb. The solar beam is less intense at the earth’s surface than in space: the light scattered from it creates the diffuse sky.

1.3 | Illuminance depends on distance and the size of the source1 |

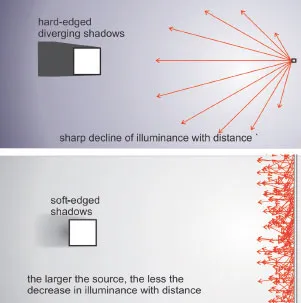

If a light source is very small, the illuminance that it gives on a surface facing it decreases greatly with distance. If the source is large, the diminution of illuminance with distance is far less.

Taking this to the limit:

If the source could be a mere point in three-dimensional space, the illuminance from it would be inversely proportional to d2, where d is the distance from source to surface. This is the inverse square law. A clear filament lamp hanging in a room is a good approximation to a point source.

If the source could be infinitely large, the illuminance it would produce would be the same whatever the distance. An overcast sky is a good approximation to an infinite plane of light.

1.3

1.4 | The crispness of shadows depends on the size of the light source |

A very small source gives hard-edged shadows that diverge. The divergence decreases with distance from the source. A large source forms soft-edged shadows.

1.4

1.5 | The luminance2 of a source depends on its size |

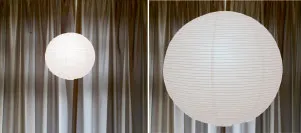

A small source is brighter than a large source with the same light output. 1.5 shows a lamp first enclosed in a small paper lantern then in a lantern of twice the diameter. The larger lantern is less bright because the same amount of light is spread over four times the surface area.

1.5

1.6

Rows of lights indicating routes. Florence, italy.

Rows of lights indicating routes. Florence, italy.

1.6 | Beacons or projectors? |

A source of light may itself be the focus of vision: a stained glass window, a candle on the dining table, a beacon buoy marking hazardous rocks at sea. Or the opposite may be true: the source may be hidden or effectively unnoticeable, entirely secondary to the light that it throws onto the surfaces around it. This is often the case when floodlighting the façade of a building or illuminating a picture on display.

When sources of light are very small in comparison with their distance from the observer, a row of them is percei...