eBook - ePub

Free at Last?

Black America in the Twenty-first Century

Juan Battle, Michael Bennett, Anthony J. Lemelle

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Free at Last?

Black America in the Twenty-first Century

Juan Battle, Michael Bennett, Anthony J. Lemelle

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

As this volume indicates, the issues facing black America are diverse, and the tools needed to understand these phenomena cross disciplinary boundaries. In this anthology, the authors address a wide range of topics including race, gender, class, sexual orientation, globalism, migration, health, politics, culture, and urban issues-from a diversity of disciplinary perspectives.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Free at Last? est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Free at Last? par Juan Battle, Michael Bennett, Anthony J. Lemelle en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Social Sciences et Sociology. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1

The Black Middle-Class: Progress, Prospects, and Puzzles

Paul Attewell, David Lavin, Thurston Domina and Tania Levey

It is exactly a century since W.E.B. DuBois published his celebrated essay about the Talented Tenth, the most educated and affluent part of the black community of his time, people whom DuBois viewed as the leaders of the race. It is instructive to investigate what has happened to the Talented Tenth over the last century, and consider the challenges still facing the African American middle- and upper-classes at the beginning of the twenty-first century. We do so in this paper by analyzing recent statistical and demographic data on the African American population, drawn from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Surveys (CPS) for 1998-2002 and the U.S. Census for 2000.

One thing quickly becomes clear: the Talented Tenth has outgrown that label. As we detail below, at least a quarter of today’s African American families are middle-class in terms of income, occupation, or education; by some measures over half of African American households are middle-class. This is not the impression that one gets from the mass media or from many social scientists, whose portraits of black America still focus on the inner-city poor, as if they were the black mainstream, while treating the African American middle-class as a small elite. In reality, since the civil rights era, a large portion of black America has moved decisively upward, passing substantial numbers of whites along the way.

One way to observe this is in terms of household incomes. In 2001, the top 5 percent of black households in America had higher incomes than 85 percent of white households. Among the former are the black business executives, athletes, and media stars who dominate the headlines, but today’s black middle-class extends well beyond this elite. The top 20 percent of African American households have higher incomes than 62 percent of white households, and the top 40 percent of black households earn more than the bottom 41 percent of white households, making them middle-class in relative terms.

The growth of the black middle-class has coincided with shrinkage in the proportion of black families living in poverty: from 34 percent in 1967 to 21 percent in 2001. Clearly many black families have not moved upward and still live in poverty. Addressing their needs is crucial, but they no longer constitute the standard for African American households.

A similar trend upward appears when we look at educational credentials. When the Harvard-educated DuBois wrote his essay in 1903, there were about 9 million African Americans in the United States, but college-educated folk were so scarce that he was able to count all 2,300 black persons with college degrees. The total African American population has nearly quadrupled since then: in the 2000 census, about 35 million persons identified themselves solely as black or African American. Of those, nearly 2 million hold bachelors degrees, and almost a million more have graduate or professional degrees. That’s more than a thousand-fold increase in black degree holders in a century.

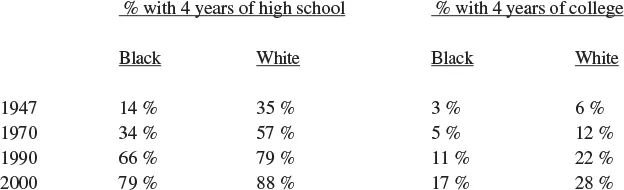

As Table 1.1 shows, most of this educational progress has taken place over the last thirty years. Although the African American growth in educational attainment has been faster than for whites, a troubling educational gap remains, an issue we’ll return to below.

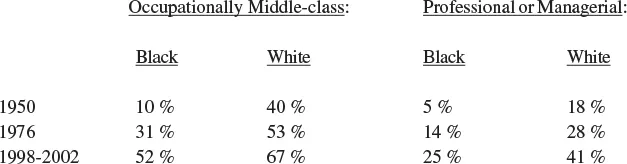

The occupational progress of African Americans has been equally striking, as Bart Landry (1987) noted. He categorized working people as middle-class if they or their spouse were employed in a white-collar or sales occupation, and he also added police and firefighters into the middle-class. One could object that classifying all white-collar workers as middle-class is too sweeping. Nevertheless, we follow Landry’s definition in updating his numbers to 1998-2002 in Table 1.2 below. In addition, we provide figures based on a more restrictive definition of Landry’s that counts only professional and managerial workers and their spouses. By either definition, the occupational progress made in a half-century is impressive.

Increased black educational attainment, occupational mobility, and movement up the income ladder—these are the major factors underlying the expansion of the black middle-class. However, immigration has also played a significant role: migrants from the Caribbean and Africa have joined the black middle-class in large numbers. The Current Population Surveys (CPS) identify individuals who are foreign-born, and those who are the offspring of such immigrants. We find that 8.7 percent of the current adult African American population was born overseas (known as “first generation” Americans) and that the U.S.-born offspring of immigrants (“the second generation”) constitute another 1.8 percent.

Table 1.1

Educational Growth and the Black Middle-Class

Educational Growth and the Black Middle-Class

Table 1.2

Occupational Growth of the Black Middle-Class

Occupational Growth of the Black Middle-Class

Immigrants and their offspring constitute a disproportionately large and successful segment of the black middle-class. Although the two immigrant generations together constitute about 10 percent of the total adult U.S. black population, they comprise 16 percent of all African Americans with bachelors degrees and 20 percent of those with masters and advanced degrees.

What holds back the further expansion and economic progress of the black middle-class?

In answering this question, we necessarily turn to difficulties that the African American middle-class faces. We limit our consideration to those economic and demographic features that can be addressed by Census and CPS data.

Unequal Pay

African Americans continue to earn less than white workers, even when one considers only year-round full-time workers with equal amounts of education, as the following table demonstrates:

If we broaden our focus to include part-time and part-year employees, the racial earnings gap widens: the average black male worker today earns 64 percent of his white counterpart’s annual earnings, or $19,227 less per year. Compared to white men, black working men on average have fewer years of education, and hold occupationally less prestigious jobs. On average, black men work about 200 fewer hours per year, are more likely to live in low-income states, and are also somewhat younger than white men. Black men also work in government more often than white males do; fewer are in the private sector or self-employed. Each of these factors tends to lower black earnings relative to whites.

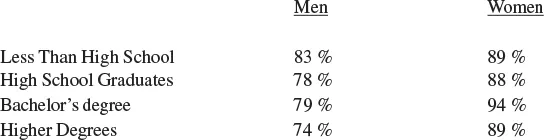

Table 1.3

Black Earnings as Percent of White Earnings, By Education.

Black Earnings as Percent of White Earnings, By Education.

When we remove all those differences using a statistical adjustment we discover what the average black male worker would earn if he was identical to the average white male employee in terms of education, hours worked, region, and so on. After making this adjustment, we find that a smaller but still substantial wage gap remains between black and white men. This adjusted gap in average male earnings is $10,0759 per year. On average, black men would earn 80 percent of what white males earn. Many scholars attribute this remaining gap to discrimination and prejudicial employer attitudes, though some suggest that the gap would narrow further if adjusted for differing skills and work experience of both groups.

In a recent review, McCall (2001) emphasized the loss/lack of manufacturing employment, a lack of union coverage, and the frequency of flexible or casual employment conditions as central to explaining the current black-white male wage gap. Grodsky and Pager (2001) stressed the over-concentration of black men in low-paying occupations, but also reported that the black-white wage gap in the private sector grows larger as one moves up the occupational or income hierarchy. In sum, the enduring wage gap between black and white men disadvantages black professional men, as well as black men in low-paid jobs, and retards the economic well-being of African American families.

The situation for black working women is not the same as for black men. The average working black woman earns $4,520 per year less in the U.S. than the average working white woman, or roughly 85 percent of the average white woman’s earnings, a smaller gap than for men. Again, there are measurable differences between the races in amount of education, hours worked, region, and occupation. When we make a statistical adjustment and ask what the average black woman would earn if she had identical years of education, hours worked etc., as the average white woman, we find that on average black women would earn more than equivalent white women, about $2,865 per year more.

Gaps in individual earnings are important for understanding racial inequality in the labor market, but, as we shall see, these earnings differences become overshadowed or overlaid by differences in household incomes between middle-class blacks and whites. Household income is affected by marriage/partner patterns and the number of earners in a household, as well as by education and wage levels. We turn next to a consideration of these interwoven factors, as they shape the fortunes of the black middle-class.

Marriageability and the Black Middle-Class

In his study of the black urban underclass, William Julius Wilson (1987) advanced the concept of marriageability to explain low rates of marriage among the black poor. Many young black males in the inner city are unemployed. Young black women, Wilson suggested, aren’t motivated to marry unemployed young black men since they cannot support a family. He concluded that this shortage of “marriageable” young men explains the lower rates of marriage found among poorer African Americans.

There are two conceptual elements underlying Wilson’s thesis. One is the idea that there is a social definition of a suitable marriage match. Wilson focused on employment, but we will also consider other possible criteria for marriageability, including education and earnings level. A second element underlying Wilson’s theory is the notion of a demographic imbalance leading to a numerical shortage of suitable members of one gender. Wilson (1987) showed that there were insufficient employed young men for the number of young single women. The result was an unbalanced marriage market leading to a depressed marriage rate. If there had been equal numbers of employed marriageable men and single women, men and women could have found suitable partners and the marriage rate would not be depressed.

Viewed in this way, Wilson’s theory is a special case of “assortative mating” a term geneticists use to denote “the preference or avoidance of certain people as mates for social or physical reasons.” Wilson’s theoretical innovation was to combine assortative mating with the notion of a numerical imbalance as an explanation of a market-wide failure to match prospective mates.

There is good empirical evidence for the relevance of marriageability criteria beyond employment. For example, researchers have documented a widespread preference for finding a partner with an educational level close to ones own, what demographers term educational homogamy (Smits et al., 1998; Qian, 1998; Raymo and Xue, 2000). As we shall see, a gender imbalance does exist among African Americans at higher levels of education: there aren’t nearly as many college-educated black men as college-educated black women. This could lead to a shortage of educationally-suitable male marriage partners and a depressed marriage rate, among the black middle-class relative to whites.

Earnings can also function as a factor in marriageability. One could imagine an earnings minimum, beneath which a male ceases to be marriageable. This would reduce the number of marriageable men, unbalancing the numbers of marriageable men and women, leaving some women unable to find a partner (cf.. Oppenheimer, 1994). This would predict very low marriage rates at low levels of male earnings, an idea close to Wilson’s unemployment thesis.

A quite different version of earnings marriageability argues, like Mare (1991) Lichter (1990), and Lindberg et al. (1997, p. 2) that:

“women need to find men with greater opportunities than their own. Therefore, women’s increased income or education would result in a smaller pool of potentially eligible partners, thus creating a barrier to their marrying...”

Their logic implies that very highly-educated women and women with very high earnings face the greatest difficulty in finding a marriage partner because there are relatively few potential husbands who earn more or have higher educational credentials than these highly-successful women.

Yet another version of imbalance allows that a new norm has emerged in recent decades that requires homogamy in earnings: both men and women want to find a partner who can earn as much or even more than themselves (Goldscheider and Waite, 1986). It follows that if an imbalance occurs between the number of men and women in a given earnings bracket, one gender or the other would face insufficient numbers of marriageable mates, and the marriage rate could suffer.

Not all scholars accept the imbalance/shortage logic. Lindberg et al. (1997) mention “an iconoclastic view” that high-earning women could afford to marry men who earn less, increasing their pool of mates and thus increasing the marriage rate for professional women (Licht...