eBook - ePub

Language Comprehension As Structure Building

Morton Ann Gernsbacher

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Language Comprehension As Structure Building

Morton Ann Gernsbacher

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This book presents a new theoretical framework -- what Gernsbacher calls the Structure Building Framework -- for understanding language comprehension in particular, and cognitive processing in general. According to this framework, the goal in comprehending both linguistic and nonlinguistic materials is to build a coherent mental representation or "structure" of the information being comprehended. As such, the underlying processes and mechanisms of structure building are viewed as general, cognitive processes and mechanisms. The strength of the volume lies in its empirical detail: a thorough literature review and solid original data.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Language Comprehension As Structure Building est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Language Comprehension As Structure Building par Morton Ann Gernsbacher en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Persönliche Entwicklung et Schreib- & Präsentationsfähigkeiten. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1

INTRODUCTION

Language can be viewed as a specialized skill involving language-specific processes and language-specific mechanisms. Another position views language (both comprehension and production) as drawing on many general cognitive processes and mechanisms. According to this view, some of the same processes and mechanisms involved in producing and comprehending language are involved in nonlinguistic tasks.

This commonality might arise because, as Lieberman (1984) and others have suggested, language comprehension evolved from nonlinguistic cognitive skills. Or the commonality might arise simply because the mind is best understood by reference to a common architecture (e.g., a connectionist architecture).

In my research, I have adopted the view that many of the processes and mechanisms involved in language comprehension are general, cognitive processes and mechanisms. This book describes a few of those cognitive processes and mechanisms, using a simple framework as a guide. It is the Structure Building Framework.

The Structure Building Framework

According to the Structure Building framework, the goal of comprehension is to build a coherent mental representation or “structure” of the information being comprehended. Several component processes are involved. First, comprehenders lay foundations for their mental structures. Next, comprehenders develop their mental structures by mapping on information when that incoming information coheres with the previous information. However, if the incoming information is less coherent, comprehenders engage in another cognitive process: They shift to initiate a new substructure. So, most representations comprise several branching substructures.

The building blocks of these mental structures are memory cells. Memory cells are activated by incoming stimuli. Initial activation forms the foundation of mental structures. Once the foundation is laid, subsequent information is often mapped on to a developing structure because the more coherent the incoming information is with the previous information, the more likely it is to activate similar memory cells. In contrast, the less coherent the incoming information is, the less likely it is to activate similar memory cells. In this case, the incoming information might activate a different set of cells, and the activation of this other set of cells forms the foundation for a new substructure.

Once memory cells are activated, they transmit processing signals either to enhance (boost or increase) or to suppress (dampen or decrease) other cells’ activation. In other words, two mechanisms control the memory cells’ level of activation: Enhancement and Suppression. Memory cells are enhanced when the information they represent is necessary for further structure building. They are suppressed when the information they represent is no longer as necessary.

Overview of Book

This book describes the three subprocesses involved in structure building, namely

• THE PROCESS OF LAYING A FOUNDATION for mental structures;

• THE PROCESS OF MAPPING coherent information onto developing structures; and

• THE PROCESS OF SHIFTING to initiate new substructures.

This book also describes the two mechanisms that control these structure building processes, namely

• THE MECHANISM OF ENHANCEMENT, which increases activation, and

• THE MECHANISM OF SUPPRESSION, which dampens activation.

When discussing these processes and mechanisms, I begin by describing the empirical evidence to support them. Then, I describe comprehension phenomena that result from these processes and mechanisms.

Let me stress that I assume that these processes and mechanisms are general; that is, the same processes and mechanisms should underlie nonlinguistic phenomena.

This orientation suggests that some of the bases of individual differences in comprehension skill might not be language specific. I have empirically investigated this hypothesis, and toward the end of this book I describe that research. But first, I describe the processes and mechanisms involved in structure building, beginning with the process I call laying a foundation.

2

THE PROCESS OF LAYING A FOUNDATION

According to the Structure Building Framework, the goal of comprehension is to build coherent mental representations or structures. The first step in building mental structures and substructures is laying a foundation. Laying a foundation should consume additional mental effort. How could we observe this additional mental effort? One possibility is increased comprehension time, and, indeed, many converging phenomena demonstrate that comprehenders slow down when they are presumably laying foundations for their mental structures and substructures.

For instance, in some experiments, researchers measure how long it takes comprehenders to read each sentence of a passage. In these experiments, subjects typically sit before a computer monitor, and each sentence of the passage appears in the center of the monitor. Subjects press a button to signal when they have finished reading each sentence; the sentence then disappears, and another one appears. In this way, researchers can measure how long subjects need to read each sentence.

A consistent finding in these sentence-by-sentence experiments is that initial sentences take longer to read than subsequent sentences (Cirilo, 1981; Cirilo & Foss, 1980; Glanzer, Fischer, & Dorfman, 1984; Graesser, 1975; Haberlandt, 1980, 1984; Haberlandt, Berian, & Sandson, 1980; Haberlandt & Bingham, 1978; Haberlandt & Graesser, 1985; Olson, Duffy, & Mack, 1984).

In fact, initial sentences take longer to read than subsequent sentences, even when the initial sentences are not the topic sentences of the paragraphs (Greeno & Noreen 1974; Kieras, 1978, 1981). According to the Structure Building Framework, comprehenders slow down on the initial sentences of paragraphs, because they use those initial sentences to lay foundations for mental structures representing paragraphs.

In addition, comprehenders take longer to read the beginning sentence of each episode within a story than other sentences in that episode (Haberlandt, 1980, 1984; Haberlandt et al., 1980; Mandler & Goodman, 1982). For instance, Haberlandt (1984) defined an episode as a Beginning, a Reaction, a Goal, an Attempt, an Outcome, and an Ending. He constructed stories that each contained two episodes, plus a setting. An example story appears in Table 2.1.

TABLE 2.1

Example Two-Episode Story from Haberlandt (1984)

Setting | Mike and Dave Thompson lived in Florida. |

They lived across from an orange grove. | |

There was a river between their house and the grove. | |

Beginning | One Saturday they had nothing to do. |

Reaction | They were quite bored. |

Goal | They decided to get some oranges from the grove. |

Attempt | They took their canoe and paddled across the river. |

Outcome | They picked a crate full of oranges and put it in the canoe. |

Beginning | While they were paddling home the canoe began to sink. |

Reaction | Mike and Dave realized that they were in great trouble. |

Goal | They had to prevent the canoe from sinking further. |

Attempt | They threw the oranges out of the canoe. |

Outcome | Finally the canoe stopped sinking. |

Now all the oranges were gone. | |

End | Their adventure had failed after all. |

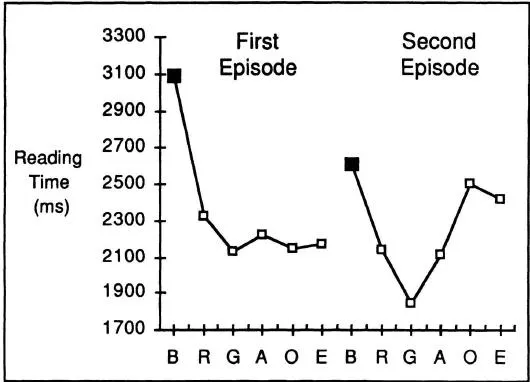

When reading these two-episode stories, comprehenders spend considerably more time reading the Beginning sentence of each episode than they spend reading any other sentence in each episode. Figure 2.1 illustrates this effect. As Figure 2.1 also illustrates, comprehenders spend considerably more time reading the Beginning sentence of a first episode than the Beginning sentence of a second episode. So, not only do comprehenders use the beginning sentence of each episode to lay a foundation for their representation of that episode, they use the first episode to lay a foundation for their representation of the entire story.

FIGURE 2.1

(From Haberlandt, 1984)

In some experiments, researchers measure how long it takes comprehenders to read each word of a sentence. In these experiments, each word appears in the center of a computer monitor, and subjects press a button to signal when they have finished reading each word. After each word disappears, another one appears. In this way, researchers can measure how long subjects need to read each word.

A consistent finding in these word-by-word experiments is that initial words take longer to read than later-occurring words (Aaronson & Scarborough, 1976; Aaronson & Ferres, 1983; Chang, 1980).1 In fact, the same words are read more slowly when they occur at the beginning of their sentences or phrases than when they occur later.

For example, the words the boat occur at the beginning of a clause in sentence (1) below.

(1) Because of its lasting construction as well as its motor’s power, the boat was of high quality.

But the same words (the boat) occur at the end of a clause in sentence (2) below.

(2) The newly designed outboard motor, whose large rotary blades power the boat, was of high quality.

Subjects read the words the boat more slowly when they occur at the beginning of a clause than when they occur at the end (Aaronson & Scarborough, 1976).

Similar phenomena occur during the comprehension of nonverbal materials, such as picture stories “told” without text. Researchers can set up a situation where subjects view each picture of a nonverbal story, one picture at a time. Although subjects can spend as much time as they want viewing each picture, subjects spend more time viewing the beginning picture of each story and the beginning picture of each episode within a story than they spend viewing later-occurring pictures (Gernsbacher, 1983).

To examine how comprehenders understand spoken language, some researchers play previously recorded sentences to subjects. The subjects’ primary task is to comprehend the sentences as well as they can. But often they have the additional task of monitoring for a specific “target” word or a specific “target” phoneme. When they hear that target word or phoneme, they press a button, and their reaction times are recorded.

A consistent finding in these monitoring studies is that reaction times are longer to identify target words or target phonemes when they occur in the beginning of the sentences or clauses than when they occur later (Cairns & Kamerman, 1975; Cutler & Foss, 1977; Foss, 1969, 1982; Hakes, 1971; Marslen-Wilson, Tyler, & Seidenberg, 1978; Shields, McHugh, & Martin, 1974).

For example, when listening for the target word bears, subjects identify it more slowly in sentence (3) than in sentence (4).

(3) Even though Ron hasn’t seen many, bears are apparently his favorite animal.

(4) Even though Ron hasn’t seen many bears, they are apparently his favorite animal.

This is becau...