eBook - ePub

Sonatas, Screams, and Silence

Music and Sound in the Films of Ingmar Bergman

Alexis Luko

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Sonatas, Screams, and Silence

Music and Sound in the Films of Ingmar Bergman

Alexis Luko

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Sonatas, Screams, and Silence: Music and Sound in the Films of Ingmar Bergman is the first musical examination of Bergman's style as an auteur filmmaker. It provides a comprehensive examination of all three aspects (music, sound effects, and voice) of Bergman's signature soundtrack-style. Through examinations of Bergman's biographical links to music, the role of music, sound effects, silence, and voice, and Bergman's working methods with sound technicians, mixers, and editors, this book argues that Bergman's soundtracks are as superbly developed as his psychological narratives and breathtaking cinematography. Interdisciplinary in nature, this book bridges the fields of music, sound, and film.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Sonatas, Screams, and Silence est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Sonatas, Screams, and Silence par Alexis Luko en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Media & Performing Arts et Music. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

PART I

A Musical Life

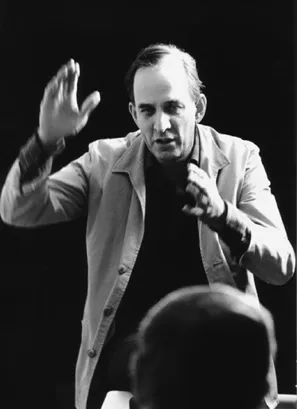

Figure 1.1 Ingmar Bergman, 1970. Photo: Bo-Erik Gyberg

Gyberg recalls Bergman reacting enthusiastically to this photo, insisting that it be published. Bergman asked Gyberg jokingly, “Where is the orchestra?” According to Gyberg, “The reason Bergman liked this picture so much was because of his profound interest in music. The photo made him appear as a conductor in front of an orchestra and he really enjoyed that” (private email correspondence between the author and Bo-Erik Gyberg, March 22, 2014).

1

AURAL CLOSE-UP

Music in Bergman’s Life

Prelude: A Musical Childhood

Music came into my life through the piano and has been indispensable ever since. More important than food and drink, it came to represent a source of solace and support.1

Ingmar Bergman, 2001

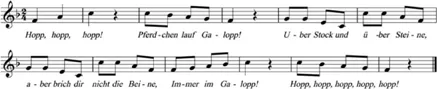

Music entered young Ingmar Bergman’s life thanks to a small fortepiano that stood in the family home. As a boy, he delighted in conducting experiments at the keyboard to study the resonance of individual notes. Upon realizing one day that he could play two tones simultaneously, he experienced the thrill of dissonance. And then, by sinking his elbows and outstretched hands into the keys and lowering his feet onto the pedals, he learned to sustain marvellous cluster chords over prolonged stretches of time, mesmerized by the blended sonorities as they lingered on and on before fading away. As Bergman described in an interview on Swedish Radio in January 2001, his first forays into music-making involved these types of naive improvisations. He admittedly “never made any melodies,” favoring instead what he described as his own idiosyncratic brand of atonal “Arvo Pärt-style” music.2 It was not long afterward that Ingmar’s mother Karin (née Åkerblom) found him a piano teacher who, he recalls, had a hairy upper lip, dentures and a wig, and smelled of Karlsson’s glue.3 A particular ditty that left a lasting impression on Bergman came by way of a children’s songbook containing the well-known German tune: “Hopp, hopp, hopp! Pferdchen lauf Galopp!” (“Jump, jump, jump! Gallop little horse!”)

Thanks to a routine enforced daily, practicing songs like this, it was not long before young Ingmar absolutely detested playing the piano. Indeed, as he explained, “the piano lessons were effectively killing my desire to experiment. They were infinitely sad … supervised, and dusty. But I learned the notes and I learned their position on the piano.”4 Still, he persevered for many years, continuing music lessons until around the age of twelve, advancing until he could play études by Carl Czerny, a composer he described as “the scourge” of all piano students.5 Bergman even tried his hand at music composition. In an interview on the Swedish Radio program Sommar, which aired on July 18, 2004, he reminisced about his childhood attempts at writing music: “I have a feeling that it was unplayable. But I thought it looked so cool and so wonderful.”6

Example 1.1 A Song from Bergman’s Childhood: “Hopp, Hopp, Hopp!”

It was abysmal boredom and a self-diagnosed “musical disability” that eventually killed his ambition to persist with his piano studies. Though he remained a great lover of music throughout his life, Bergman described an “embittered struggle” when it came to personal music-making of any variety. All too aware of his deficiencies, he was unable to take pleasure in playing the piano, singing, or even whistling. As he wrote in The Fifth Act:

My love for music is unrequited. I lack an ear or memory for melody. But it doesn’t much matter. The most important thing is not to be loved, but to love. If I had been talented and had not become what I have become, I would have in all probability been a music conductor. It is true that I’m completely deaf in my right ear since my military duty, when I was in charge of a so-called M-14 machine gun. But my left ear can still hear a cricket sing. My right ear is what they call legally blind, but I can see like a raven with the left one.7

Perhaps as a result of the hearing damage from his time in the military, Bergman developed more severe problems with his hearing later in life. He often complained of suffering from hyperacusis – a condition involving severe aural hypersensitivity, causing normal noises to sound painfully amplified. As a result, he was unable to withstand the noises of vacuums, and lawnmowers, and also complained about amplified airplane speaker announcements and untuned pianos.8

Bergman also blamed his musical shortcomings on a “total inability to remember or repeat sequences of notes.”9 He recalled his fruitless attempts at making music, working day after day with a tape recorder and score – a paralyzing experience that made him all too aware of his lack of skill. He would force himself to “spend an inordinate amount of time learning musical works … listening to every bar, every beat of the pulse, every single moment.”10 Though he complained of being utterly unable to sing or whistle a tune, in an interview with Vilgot Sjöman, Bergman admitted he knew instinctively that he was not altogether unmusical, and expressed a suspicion that there were probably deep underlying psychological issues hindering him from pursuing a musical career.11

Early Musical Likes and Dislikes

Bergman developed a special penchant for old keyboards (particularly organs, harpsichords, and square pianos) and percussion instruments, the sounds of which drove him into states of joyful euphoria.12 Proof of his passion for percussion is found in soundtracks accompanying the opening credits and intertitles of most of his films. He had other fond musical memories of the household maids (Siri, Alma, and Maj), described as “big warm good girls,” who would often sing folk songs and tell haunting tales about ghosts and murder. These are memories revisited in the fictional world of Fanny and Alexander (where the names Siri and Maj resurface, associated with Fanny and Alexander’s nannies) and similar types of grotesque stories are shared between Alexander and Justina, the maid at the Bishop’s residence.13

Bergman frequently retold a story about a man he referred to as his “uncle,” who would often dine in the family home and regale the Bergmans with after-dinner music:

I remember especially one time – it’s my first memory of music. He played a piece, a folksong from Dalarna. Yes, then something terrible happened. This is a tune in a minor key, which is not too uncommon among folksongs. But I began to cry … I had held myself together for a long time and I remember having a vision. At that time … a close friend to our family had passed away. And we went to see her – everyone, all the children, my brother, my sister, me, and my parents – all went to bid farewell to the dead. And the dead lady was already in her coffin, at home in the apartment. I was not afraid but the experience made an incredibly strong impression on me, and that was the main reason why I began to cry. The music painted a picture of my mother in a coffin and I was deeply in love with my mother so I could not endure the thought and broke down completely. Someone in the family helped me up to the nursery and sweet Uncle Einar, terribly humiliated, said, “So the boy did not like the music!” I remember hearing those words very clearly just as I went up the stairs to the nursery. But never have I denied how the music connects itself to time; this memory is so clearly etched in my mind and is so present with me today that I can relive it whenever I want.14

Born out of this experience, it is no wonder that Bergman’s least favorite instrument came to be the violin, which he claimed to find unbearable in the hands of any musician other than Isaac Stern.15 Functioning like a death knell, the violin triggered violent crying attacks and, associated with a mixture of painful memories and forebodings of his mother’s demise, it continued to haunt him throughout his life. It is, perhaps, for this reason that his film To Joy (examined in Chapter Four), which follows the career of a concert violinist, is marked by misery, death, and exceedingly poor violin playing.

Bergman’s adolescence was accompanied by the gritty Weimar cabaret sounds of Lotte Lenya and the Lewis Ruth Band. He was particularly fond of a Telefunken LP recording from 1931 conducted by Theo Mackeben, featuring numbers from Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera and The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.16 In a radio interview, Bergman describes his first contact with Weill’s music on vacation in 1934, during an extended visit with a host family in Germany:...