Background to the Action

This chapter outlines the history to, and achievements of, the COST Action ‘The Digital Literacy and Multimodal Practices of Young Children’ (DigiLitEY), an Action which led to the development of this Handbook as one of the key outputs of the network. COST Actions are funded by the EU Commission as a means of drawing together networks of researchers to work on topics of import (see https://www.cost.eu). The chapter provides an overview of the work undertaken by DigiLitEY members. First, however, the rationale for the Action is outlined.

Research has identified the ubiquitous nature of new technology in young lives and has explored related practices. Children aged from birth to eight have access to and use a wide variety of technologies (Rideout 2014; Chaudron et al. 2015; Marsh et al. 2015; Ofcom 2017). Over the past decade there has been a substantial increase in internet use by the under-eights, although this is not uniform across countries, and even if they do not use the internet, children may have well-established digital footprints, created by family members (Holloway, Green and Livingstone 2013). Many children access online sites or apps to play games, watch videos, visit virtual worlds and also they use sites and apps related to popular television programmes and popular literature (Burke and Marsh 2013; Ofcom 2017; Marsh et al. 2019; Rideout 2014). Children engage online with other users who are both known and unknown to them in their everyday lives (Burke and Marsh 2013; Chaudron et al. 2015), and in some families whose members are geographically dispersed, children, from the first months of life, communicate with family members using video communication apps/sites, such as Facetime and Skype (Kelly 2015; Marsh et al. 2015). Children develop a wide range of digital literacy skills as they engage in these daily practices (Marsh 2016; Marsh et al. 2019).

A second area of focus of research in the area has been children’s digital literacy skills development and the role of parents, kindergartens and schools in this process. Children are engaged in reading, writing and multimodal authoring/design across a range of screen-based media in homes and communities, although there are differences in families due to socio-economic status and family histories (Chaudron et al. 2015; Marsh et al. 2015; Nevski and Siibak 2016). In this use, children draw upon their interactions with digital texts and develop strategies to make sense of a variety of symbolic representations, including print, and vice versa (Flewitt 2011; Harrison and McTavish 2016). Well-designed tools can facilitate children’s learning, such as e-books, which can support children’s understanding of stories and story language (Smeets and Bus 2012; Kucirkova, Littleton and Cremin 2017). Children’s engagement with age-appropriate apps on tablets can extend their knowledge and skills in multimodal communication (Flewitt, Messer and Kucirkova 2015; Kucirkova and Littleton 2017). Family members support children’s interaction with technologies in a range of ways, scaffolding interaction with games, sites and apps and guiding acquisition of technical skills (Plowman, Stevenson, Stephen and McPake 2012). There has been less research on the impact of technologies on the media ecology of the family as a whole, and then how this impacts on the parenting of young children. Lahikainen, Mälkiä and Repo (2017), in a project that involved the collection of 665 hours of video data from 26 Finnish families, argue that family members may be “together individually”, in that family members may pursue individual activities using digital media while being physically co-present, and they suggest that the use of a “sticky media device”, such as a smartphone, can disrupt family social discourse, with young children not always being able to work out the nature of the communication taking place through such devices. A recent survey (Livingstone, Blum-Ross, Pavlick and Ólafsson 2018) of parents of children aged 0–17 in the UK suggests that digital media bring families together rather than separating them, and the authors argue that parents try hard to ensure their children can benefit from technologies and manage risks, but that they feel they do not have sufficient support for dealing with digital dilemmas.

Another focus for research in the field has been on the use of technologies in early childhood education. In kindergartens and schools, effective pedagogy and curricula for the development of children’s digital literacy skills in the early years are distinguished by an emphasis on play, collaboration, creativity and the co-construction of knowledge (Sandvik, Smørdal and Østerud 2012; Yelland and Gilbert 2014; Dezuanni, Dooley, Gattenhof and Knight 2015; Harwood et al. 2015; Lee 2015). Early years teachers need professional development in this area in order to support their pedagogical practice (Arrow and Finch 2013).

A fourth area of research in the field has been the social and cultural value of children’s digital literacy practices and the impact of the online/offline dynamic on this area. Young children’s play with new technologies is important for enabling them to rehearse the social practices of digital literacy in the wider world (Medina and Wohlwend 2014). Young children construct and perform online identities drawing on their offline resources, yet this does not always equip them for the environments and experiences they meet in online social networks (Burke and Marsh 2013). There is an increasing synergy between children’s online and offline digital literacy practices, with the growing proliferation of apps and toys that make use of this dynamic, such as those that embed augmented reality (AR) (Marsh and Yamada-Rice 2016).

Finally, a number of studies have identified the lack of attention to the digital literacy practices of young children in national policies. Although literacy is defined internationally as “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, compute and use printed and written materials associated with varying contexts” (UNESCO 2013), which does not privilege any specific mode, national curricula tend to continue to define early literacy in traditional terms, that is, focusing on alphabetic code (Flewitt 2011; Sefton-Green, Marsh, Erstad and Flewitt 2016).

At the beginning of this Action, in 2015, European work in this area was world-leading and internationally recognized, but was fragmented in nature. In addition, there was a need to develop multi-disciplinary approaches to these vital areas of research. New knowledge was required on a range of issues, including young children’s access to and use of smartphones and tablet computers in homes and community spaces across Europe, and the way in which families support children’s engagement in wider social networks through digital media environments. Further, while there had been a number of studies of digital literacies in early years settings, as outlined above, there was a need to identify key areas that deserved further attention, in particular the training needs of early years practitioners. Finally, given the rapidly changing nature of technologies, knowledge was required of the impact of emerging and future technological developments on practices across homes, community spaces (such as museums, libraries and civic spaces), kindergartens and schools. The aim of the Action was to draw together the current knowledge base of research in this area, and to identify the key gaps in the research that required collaborative, concerted action. The Action was joined by researchers from a range of disciplines, including: Communication and Media Studies, Education, Linguistics, Psychology and Sociology, which enabled an interdisciplinary perspective to be undertaken on these issues.

This work was undertaken in a context in which there was growing attention paid to the need for children to develop what have been characterized as ‘21st Century Skills’. There are various models of such skills (see van Laar, van Deursen, van Dijk and de Haan (2017) for a review), but they generally identify the following skills and dispositions as being key to meaning-making in the digital world: communication; cultural understanding; problem-solving; creativity; collaboration; and an ability to manage information. These skills are important if young children are to be prepared effectively for the employment and leisure opportunities of the future, which will be shaped, some argue, by the “fourth industrial revolution” (Schwab 2016). However, while the work on 21st-century skills has been useful in identifying the range of transferable skills required in a post-digital (Cramer 2015) future in which online and offline, digital and non-digital domains blend seamlessly, it does not provide a clear theoretical framework for a focus on digital literacy. Therefore, one of the first tasks undertaken by the Action was to develop a shared understanding of digital literacy, outlined in the following section.

Digital literacy

The phrase ‘digital literacy’ refers to the literacy practices of young children as they are undertaken across media. This is not unproblematic. Digital literacy has been adopted as a term used to refer to the digital competences children and adults may acquire through the use of digital technologies (van Laar et al. 2017). Thus, it has, in Barton’s (2007) framing become a metaphorical term, as is the case with other phrases in which literacy is used as a signifier for skills and competence, such as ‘computer literacy’, ‘information literacy’ and so on. In addition, European research and policy have a long-established engagement with work in the field of ‘media literacy’. How, then, can digital literacy be useful as a concept? The following discussion was outlined in an Action White Paper, which informed our work across the four years of operation of the consortium (Sefton-Green et al. 2016).

Digital literacy can be defined as a social practice that involves reading, writing and multimodal meaning-making through the use of a range of digital technologies. It describes literacy events and practices that involve digital technologies, but which might also involve non-digital practices. Thus digital literacy can cross online/offline and material/immaterial boundaries and, as a consequence, create complex communication trajectories across time and space (Burnett, Merchant, Pahl and Rowsell 2014). Using ‘reading’ and ‘writing’ in their broadest terms, digital literacy can involve accessing, using and analysing texts in addition to their production and dissemination.

Digital literacy does involve the acquisition of skills, including traditional skills related to alphabetic print, but also skills related to accessing and using digital technologies. In this category might also be included skills related to the processes involved in accessing, using and creating knowledge. In this sense, our understanding of digital literacy has synergies with those definitions that focus on competences. However, we must move beyond a focus on skills if we are to understand how children’s digital literacy develops in a more holistic sense. To do this, the Action drew on Bill Green’s (1988) 3D model of literacy.

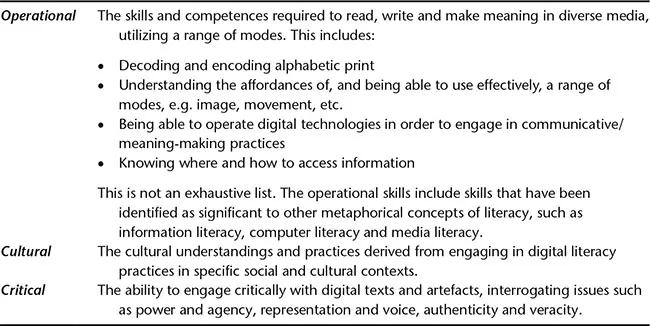

Green (1988) originally developed his 3D model of literacy in an era when the focus was still largely on traditional print practices although recently, he has argued that the model can be adapted to include an emphasis on communication in a digital age (Green and Beavis 2012). Green (1988) suggests that there are three elements involved in considering literacy as a social practice – the operational, cultural and critical. Operational elements include those skills needed to become a competent communicator, such as being able to decode and encode alphabetic print. Cultural competences include understanding literacy as a cultural practice and being able to read the cultural signs embodied in acts of meaning-making. The third element of the model, the critical, emphasizes the need for critical engagement with texts and artefacts of all kinds, the need to ask questions about power, about intended audience and about reception. If the 3D model is applied to digital literacy, then the three elements can be defined as set out in Table 1.1:

The three dimensions do not operate in a linear manner, but inter-relate. More recently, Colvert (2015) has adapted Green’s model to identify the way in which the processes involved in meaning-making can be inflected by all three dimensions. Drawing on Kress and van Leeuwen (2001) and Burn and Durran (2007), she identified the following as key elements in the meaning-making process: design; production; dissemination and reception.

Table 1.1 Green’s (1988) 3D model of literacy

These might be explained by focusing on the actions of rhetors. A rhetor is an individual who wishes to communicate a message. The message can take the form of a text or artefact. It is important to acknowledge that a text can be defined very broadly – the term does not simply refer to written texts (Kress 2010). In the design stage, the modes in which the message will be conveyed are decided upon. In the production stage, the producer, who might or might not be the same person as the rhetor/designer, creates the text/artefact using the mode and media decided upon in the design stage. The producer might or might not meet all of the original intentions of the rhetor/designer (Colvert 2015). The message is then disseminated through the chosen media, for example paper, the internet, a combination of both, and so on. At the reception stage, the audience engages with the text/artefact a...