eBook - ePub

Routledge Revivals: Chinese Art (1935)

Leigh Ashton, Leigh Ashton

This is a test

- 111 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Routledge Revivals: Chinese Art (1935)

Leigh Ashton, Leigh Ashton

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

First published in 1935, this book was intended to provide westerners with a more definite and comprehensive understanding of Chinese Art and its achievements. Newly available opportunities to study authentic examples, such as the Royal Academy exhibition that provided the impetus for this volume, allowed for greater opportunities to conduct in-depth examination than had previously been possible. Following an introduction giving an overview of Chinese art and its history in the west, six chapters cover painting and calligraphy, sculpture and lacquer, 'the potter's art', bronzes and cloisonné enamel, jades, and textiles — supplemented by a chronology of Chinese epochs, a selected bibliography and 25 images.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Routledge Revivals: Chinese Art (1935) est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Routledge Revivals: Chinese Art (1935) par Leigh Ashton, Leigh Ashton en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Kunst et Kunsttechniken. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

The Potter's Art

by

R. L. HOBSON

R. L. HOBSON

THE ceramic greatness of China begins comparatively late in a history that goes back beyond the days of Homer. It is true that a people which settled in the regions now called Kansu, Honan and Manchuria left behind them a painted pottery of remarkably advanced technique, thin and fine-grained in body, well shaped with the aid of the slow wheel, if indeed the fast wheel was not actually used, and strongly baked. But this pottery, strikingly handsome as some of it is, plays little or no part in the evolution of the Chinese ceramic art. Its red- and black-painted ornament is akin to that of the more Western wares found at Tripolye, Anau, Susa, Ur and even in the Indus Valley, suggesting that a race which spread over these wide regions actually sent out a branch across Asia into prehistoric China. But whether the people of the painted pottery withdrew, were destroyed or were absorbed, their art, at its best in the earliest stages, degenerated and disappeared without having any lasting influence.

The primitive pottery, which is more truly Chinese, is a coarse grey ware whose only ornament at first was the impression of matting or a few roughly incised patterns. This is found side by side with the painted ware, but it is far more widely distributed and its evolution can be traced from the second millennium B.C. down to Han times (206 B.C.-A.D. 220). In the Yin and Chou periods it borrowed the ornament of the contemporary bronzes, and in certain important centres, where suitable clay was found, it became a fine white pottery of definitely artistic pretensions.

But the most important stage in Chinese ceramic development was reached with the introduction of glaze. Glaze, the glassy coating which makes pottery watertight and fits it for a hundred household uses, gave it at once an important place in domestic economy, and from this stage the evolution of pottery into a thing of beauty was assured.

It would be interesting to know exactly when the Chinese first made use of glaze and whether they evolved the idea themselves or borrowed it from Western Asia. All we know so far for certain is that it was in use in the Han Dynasty, which ruled from 206 B.C. to A.D. 220, a period when contact with Western Asia was firmly established. Archaeologists to-day are busy searching for evidence of glaze in China in the Chou Dynasty (1122-249 B.C.), but proof of this is still far from complete, though there is at least one known specimen with glaze over ornament of Chou bronze type which renders the supposition probable.

The typical Han glaze is a lead silicate such as is found on contemporary Roman pottery. It has a natural, warm yellowish tint which over the typical red pottery of the time produces a brown colour. But it was usually coloured with a copper oxide which transforms it into leaf-green; and many of the Han glazes to-day have an adventitious beauty, due to long burial which has dissolved the soft lead glaze into layers of gold or silver iridescence.

Another glaze, and one of unquestioned Chinese origin, can be traced at least as far back as the end of the Han period. It is derived from wood ashes and only forms on pottery fired at a relatively high temperature, over which it spreads a strong brown skin. We have here, in fact, a brown-glazed stoneware which may perhaps be regarded as the first tentative stage in the evolution of porcelain.

It was not, however, for many centuries that glazed pottery became the rule in China. In our collections of early wares up to the end of the T'ang Dynasty (A.D. 618-906) glazed and unglazed pottery stand side by side.

Our acquaintance with the early pottery, ranging from the Chou to the end of the T'ang Dynasty, extensive as it is, is confined to excavated objects; and these are not so much the pottery of everyday use as special wares made for funeral purposes. The prevalent idea that the spirit of the dead followed the pursuits which had engaged him in life, led first to the sacrifice of human beings and domestic animals at the tomb, and later, when humaner counsels prevailed, to the burial of models made of straw, wood, clay and occasionally metal. And so the excavated tombs have yielded a host of pottery figures of men, women, animals, birds and superhuman creatures, besides models of houses, furniture, farm buildings, implements and utensils of all kinds. These give us a glimpse of the life and habits of the ancient Chinese, of their costumes and equipment, and they are of much antiquarian interest. Nor are they lacking in artistic merit, for many of the figures are modelled with skill and force, and even the banalities of farm buildings—the granary, the well and the sheep pen—are transformed into ornamental objects by a clever conventionalization.

But it is only occasionally, ana in the tombs of the great and wealthy, that pottery of high finish and real artistic merit has been found, and from this we can guess at the superior quality of the wares which must have furnished and adorned the houses of the well-to-do.

The pottery with lead glaze and the hard ware with wood-ash glaze continued in use throughout the period from Han to T'ang, and with it have been found quantities of unglazed ware which is usually tricked out with coloured pigments—white, black, blue and green. These pigments are not fixed by firing and are liable to rub off if handled. Such wares, unsuited for daily use, were obviously designed for funeral purposes. Nor have they anything in common with the ancient painted pottery of the Honan and Kansu type, though the fact that both are painted might suggest some relationship. Occasionally the painted designs include human figures, animal life and even rough landscape, linking them with the earliest Chinese painting on silk; but as a rule they consist of bands of formal ornament, often derived from the decoration of bronze vessels.

Frequently too the pottery shapes at this time are based on bronze models, if indeed the pots are not actually cheap replicas of bronze.

Many of the tomb figures of this intermediate period, particularly those in a blackish clay relieved by lively pigmentation, are modelled with a vivacity and humour not surpassed in the more sophisticated creations of the Tang Dynasty. These black ware figurines are commonly attributed to the Northern Wei Dynasty (A.D. 386-535).

The wares of the T'ang Dynasty (A.D. 618-906) in their variety of technique and decoration show that the potter's art had made notable progress. The funeral pottery was still as a rule made of a soft, low-fired material, usually white or pinkish white; and it was generally covered with a transparent glaze which was either colourless or of a pale straw tint. On the more elaborate specimens the glaze is variegated by dabs of colouring oxides producing blue, green, and amber yellow patches, streaks and mottling (Pl. X). The modelling of figures, especially that of horses and camels, is often remarkable for lifelike vigour and dramatic action; and the forms of vases, jars, ewers and other vessels display a fuller development of the ceramic sense. Graceful shapes flow from the potter's wheel to be enriched with well-balanced ornament, incised or in stamped relief or touched with polychrome glazes. The brush too is used for tracing designs in black pigment or in coloured clay "slips".1 And even in the T'ang funeral wares we realize that the greatness of the Chinese potter was already established.

Somewhere in the four centuries between Han and T'ang was evolved that wonderful discovery which has made the whole world China's debtor. There is no record of the invention of porcelain and there was probably no inventor. It doubtless came from the tentative use of certain clays with which certain districts in China are richly endowed. The essential elements of porcelain are china clay (kaolin) and china stone (petuntse), a decomposed felspar. Analysis of some of the wood-ash glazed wares made quite near the Han period shows the presence of kaolin; but it is a far cry from these reddish stone-wares to the white translucent material which we call porcelain.2 It is true that our definition of porcelain is far stricter than that of the Chinese equivalent tz'ǔ. Neither whiteness of body nor translu

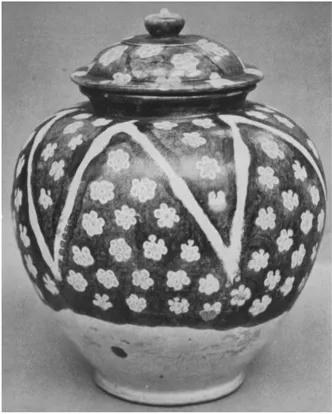

PLATE X

COVERED JAR: EARTHENWARE: CHEVRON DESIGNS IN COLOUR

COVERED JAR: EARTHENWARE: CHEVRON DESIGNS IN COLOUR

T'ANG DYNASTY (A.D. 618-906)

H. 10·15 in.

British Museum, London

(Eumorfopouhs Collection)

cency are essential in the latter, the one indispensable condition being that the ware be hard and compact enough to give a musical note on percussion. Many of the Sung wares for instance which are classed as tz'ǔ have grey or even brown body material, and would rank in our classification as stoneware or something between it and porcelain proper. This circumstance makes it useless to try and trace the origin of porcelain by reference to literature. But tz'ǔ certainly includes white porcelain in its meanings and we have at any rate an allusion to white tz'ǔ (pai tz'ǔ) in sixth-century annals, which may fairly be assumed to connote white porcelain. By the ninth century white porcelain was already an article of commerce; and many fragments of it, as well as of green celadon porcelain, have been dug up at Samarra, on the Tigris, beneath palace buildings which were only used for about fifty years during that century.

Even among the T'ang tomb wares there are many which are hard enough to qualify for the title tz'ǔ. Whether they were made merely by firing the soft white ware to an unusually high temperature or whether they have a special composition, they have bodies which a knife will not scratch and they are of a white or light buff colour. We may assume that the finer domestic T'ang ware, as distinct from the funeral goods, was generally of this harder and more practical material. At any rate Samarra has given us, in addition to white porcelain, fragments of a hard buff ware covered with typical T'ang mottled glaze, and the Samarra wares may be taken as samples of the ordinary Chinese domestic wares of the period. On these hard, porcellanous bodies we find other types of glaze, which are more refractory and evidently contain a felspathic element. Their colours include white, black, a watery green of celadon type, true celadon, and a chocolate brown which is occasionally, and probably by accident, variegated with splashes of milky grey and blue.

These technical developments lead on to the great period of monochrome porcelains, the Sung Dynasty; but the high-fired T'ang wares, as we know them, are not artistically equal to the best of the soft-glazed pottery. Some of this, such as the dishes with elegant "mirror" patterns strongly incised and filled in with washes of blue, green, and amber, are really beautiful; and there is a covered potiche (ex Eumorfopoulos collection) in the Exhibition which shows this type of ware at its best. It is one of the loveliest pieces of pottery in existence.

But it is clear that T'ang pottery, revealed through the imperfect medium of the funeral wares, leaves much to our imagination. We can only guess at its splendid possibilities. The T'ang was a classic period for poetry, painting and sculpture, and we may be sure that the minor arts did not lag far behind. The grand pottery figures of Lohan, of which the noblest can be seen in the British Museum, and the lovely Eumorfopoulos potiche both suggest that ceramic art in the T'ang Dynasty rose to a greatness of which we have so far only been vouchsafed a glimpse.

The five short dynasties which crowded the interval between T'ang and Sung (A.D. 906-960) are noted in ceramic annals for two kinds of ware. One is the almost mythical Ch'ai ware reputed to have been "blue as the sky after rain, thin as paper and resonant as a musical stone"; the other is the pi-sê (secret colour) ware of Yüeh Chou. The Ch'ai was made for a few years only and for the exclusive use of the Emperor Shih Tsung who reigned from A.D. 954 to 959. Though specimens in various collections from time to time have been hopefully labelled Ch'ai, they all differ widely in their nature and none can so far be considered convincing.

The pi-sê ware on the other hand has been identified. The factory site has been located at Yü-yao Hsien, near Shao-hsing Fu (formerly Yüeh Chou) in northern Chekiang; and the fragments unearthed there belong to the green-glazed, or celadon, family, though the green has a decided tinge of grey or olive. From A.D. 907 to 976 the pi-sê ware was reserved for the private use of the princes of Wu and Yüeh; but it was made before this, in the T'ang Dynasty, and it continued during the Sung.

THE SUNG PERIOD

With the Sung Dynasty (A.D. 960-1279) we enter on one of the great periods of Chinese art, which was nurtured by imperial patronage and favoured by long periods of peace and prosperity. The ceramics of the period are fortunately known to us by something better than funeral wares, for enough of the finer Sung specimens have been preserved above ground to allow us to appreciate their true worth. Ceramic historians, too, have given us descriptions—too brief, it is true, and not free from tiresome ambiguities—of the most noted Sung factories and their productions; and efforts are being made to-day to locate the pottery sites and search for sherds and "wasters" which should make the identification of the wares a certainty. Some of these excavations have already been fruitful, and it is hoped that the Chinese, realizing at length that the spade is mightier than the pen, will persevere in this important form of research.

Historians are agreed that of the numerous Sung wares six are of outstanding merit: the Ju yao1 made at Ju Chou in Honan and in a special kiln set up within the palace precincts at K'ai-feng Fu; Kuan2 yao, made first at K'ai-fêng Fu and after 1127 at the southern capital, Hangchow; Ko yao, reputed to have been made in the Lung-ch'üan district of Chekiang; Lung-ch'üan yao, the typical green-glazed, celadon, porcelain of that district; Ting yao, a white porcelain made at Ting Chou in Chihli; and Chün yao, made at Chün Chou, the modern Yü-hsien, in Honan.

To these may be added the Chien yao made at Chienning Fu in Fukien, the Tz'ǔ Chou wares made near Shuntê Fu in the southern corner of Chihli, and a few others.

The Imperial Ju yao was made by selected potters transferred from Ju Chou to the palace precincts at K'ai-fêng Fu, for a few years only before 1127 when the Sung court was driven south by the invading Tartars. It has long eluded identification, in spite of the fact that it has been described in detail by C...