![]()

Part One

![]()

TWO

Benefits, pensions, tax credits and direct taxes

John Hills, Paola De Agostini and Holly Sutherland

What is now often referred to as ‘welfare’ is the most contentious, but often least understood, part of social policy. At its broadest, ‘welfare’ could mean the whole welfare state — including the twothirds of public spending that goes on healthcare, education, housing and personal social services, as well as cash social security benefits, including pensions. At its narrowest – following US terminology, and often accompanied by similar stigmatisation – it could mean cash payments to working-age people who are not in work (about a twentieth of public spending). In between, it could refer to what are, for clarity, described here as ‘cash transfers’ – social security benefits (including state pensions) and tax credits. 1

A popular perception is that the 1997-2010 Labour government greatly increased spending on benefits and tax credits, particularly for those out of work, creating much of the deficit by the time it left office, and in some versions causing the financial and economic crisis itself. The coalition government coming to office in May 2010 set reducing the deficit as its highest priority, and argued that the ‘welfare budget’ should make a major contribution – albeit with state pensions largely protected. Some of the resultant cuts became among its most controversial policies.

This chapter examines what actually happened to cash transfers in the period since the crisis started, looking at policies in the final years of the Labour government2 from 2007/08 and under the coalition, levels of public spending, benefit levels and the distributional effects of policy change (including direct taxes) since 2010. These form part, alongside other developments, such as in the labour market (see Chapter Six), of what drove the changes in poverty and inequality discussed later in this book, in Chapter Eleven.

The situation on the eve of the crisis

Labour’s aims for poverty and inequality were selective. Child and pensioner poverty were key priorities, alongside wider objectives for life chances and social inclusion. Equality was discussed in terms of ‘equality of opportunity’, not of outcomes, with little emphasis on inequalities at the top.

Correspondingly, Labour’s spending increases concentrated on families with children and pensioners. Its emphasis for the working-age population was on education, training, ‘making work pay’ (including the first National Minimum Wage), and support into work. A major reform was to transform means-tested cash benefits for working families with children, first, from 1999 into a more generous Working Families’ Tax Credit, and then, from April 2003, into Child Tax Credit (going to families in and out of work in an integrated system) and Working Tax Credit (for the first time going to those without children). Both were designed to mimic Income Tax, being adjusted after the end of the year to reflect income changes over the year. An explicit aim was to reduce the stigma attached to claiming in-work benefits through the changes in name and administration, reinforcing the ‘making work pay’ message, but with the side-effect of often requiring unpopular clawbacks from tax credits paid the following year. For pensioners, the initial strategy was based on improving means-tested minimum incomes.

Spending on working-age cash transfers unrelated to having children fell in real terms between 1996/97 and 2007/08 (see Figure 2.2) and as a share of GDP. Despite more generous treatment of families with children and pensioners, overall spending on cash transfers was the same 10% share of national income in 2007/08 as in 1996/97 (see Figure 2.1 later in the chapter). This is far from the caricature that Labour greatly increased ‘welfare spending’ in advance of the crash, especially on ‘handouts’ to those who were out of work.

The results matched Labour’s priorities and spending. By 2007/08, child poverty had fallen by 4 percentage points since 1996/97 before allowing for housing costs (3 points after allowing for them). Given the difficulty of making progress against the ‘moving target’ of a relative poverty line over a decade with strongly rising overall living standards, this was an achievement, but was far short of Labour’s target of halving child poverty by 2010, let alone ‘eliminating’ it by 2020.3 Pensioner poverty had fallen faster – by 3 percentage points before housing costs (BHC) or 10 points (two-fifths) after them (AHC).4 On the other hand, relative poverty for working-age adults was unchanged, and indeed rose for those without children.

Taken as a whole, Labour’s tax and benefit policies had redistributed modestly (if compared to the system it inherited adjusted for income growth) from the top half of the income distribution to the bottom half,5 although Labour avoided the use of the word ‘redistribution’. This, and its other policies, kept income inequality across the bulk of the population (as measured by the ‘90:10 ratio’) roughly constant before housing costs between 1996/97 and 2007/08 (with a small rise after housing costs). But it was not enough to stop a significant rise in inequality across the whole population, allowing for rapidly rising incomes at the very top (as measured by the Gini coefficient); see Figure 11.3 in Chapter Eleven.

Policies since 2007

Labour under Gordon Brown

In many ways the most important policy for cash transfers followed after the crash, with Gordon Brown as Prime Minister from June 2007, was to continue to increase them with inflation (generally measured by the retail price index [RPI]). The coalition did the same initially. The macroeconomic – and political – arguments against cutting real transfers during a recession are outside the scope of this book. But this protection in bad times was consistent with working-age adult benefits not increasing during the preceding good times when real incomes for those in work rose. As wages – and with them net incomes for those in work – fell in real terms during the recession, this policy of protecting incomes at the bottom acted to reduce relative poverty and inequality.

Combined with increases in tax credits for children in 2008/09 and the effects of rising unemployment, real spending on cash transfers as a whole rose and, with GDP falling, the share of national income going on cash transfers rose faster, by 2 percentage points between 2007/08 and 2009/10 (see Figures 2.1 and 2.2 later). This is what would be expected from a system designed to stabilise incomes in hard times.

Labour’s major structural reforms for non-pensioners were already in place before Gordon Brown became Prime Minister, implemented while he was Chancellor. But its main pension reforms came following the recommendations of the independent Pensions Commission in 2005 (see Evandrou and Falkingham, 2009). Through the Pensions Acts of 2007 and 2008 Labour improved the future value of state pension rights, including widening rights to a full pension, improving its value for lower earners, and returning to linking pension values to earnings (planned from 2012), but with the State Pension Age due to rise from 65 after 2024. It also introduced ‘automatic enrolment’ of employees into employer pension schemes or a new low-cost National Employment Savings Trust (NEST), but with the right to opt out. The reforms were designed to halt the growth of means-testing in old age that would otherwise have occurred, giving clearer incentives to save for retirement and a lower-cost way of doing so.

A controversial change to Income Tax early in the period was the abolition from 2008/09 of Labour’s own reduced starting ‘10p band’ at the same time as the main rate was cut to 20%. The combination of the two left some low earners who were not entitled to (or did not receive) tax credits as losers, even after an emergency increase in the general level of tax allowances the following autumn. Just before it left office, Labour made revenue-raising changes to direct taxes. From April 2010 the tax-free Income Tax personal allowance was tapered away from those with incomes above £100,000, and a new top rate of 50% was applied to slices of income above £150,000 per year. Labour also announced that National Insurance Contribution (NIC) rates would rise from April 2011.

Coalition aims and goals

It is striking how coalition policy was dominated by the inclusion in the initial coalition agreement and subsequent Programme for government (HM Government, 2010) of two key – and expensive – Liberal Democrat aims, a £10,000 tax-free allowance for Income Tax, and the basic pension increasing with a ‘triple lock’ from 2011 (the higher of price inflation, earnings growth or 2.5%). At the same time, other benefits for pensioners would be protected, as promised by the Conservatives, such as Winter Fuel Payments, free bus passes and free TV licences for older people. The promise to raise the annual tax-free Income Tax personal allowance to £10,000 was a huge pledge at a time of fiscal crisis.6 As only a minority of the tax measures proposed to finance it were implemented, finding other savings to balance its cost became crucial.

The coalition maintained the goal of ‘ending child poverty in the UK by 2020’ (HM Government, 2010, p 19), but tax credits would be cut back for higher earners, and their administration reformed ‘to reduce fraud and overpayments’. Otherwise comparatively little was initially agreed on working-age benefits. However, after the election, Iain Duncan Smith was appointed as Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, bringing with him plans from the Centre for Social Justice, which he had established in 2004, to unify means-tested benefits and tax credits in what became the coalition’s centrepiece Universal Credit.7

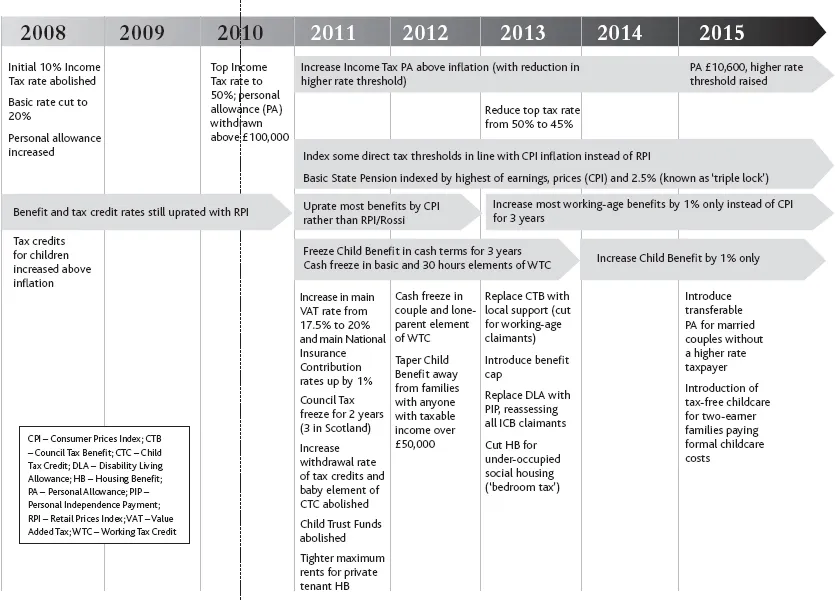

This longer-term reform would, however, come after a series of specific cuts and reforms to working-age benefits. These smaller reforms, alongside decisions on how to uprate benefits from year to year, dominated what happened to cash transfers and their distributional effects up to 2015/16. Box 2.1 gives a timeline of these reforms.

Coalition policies

The coalition’s policies towards cash transfers and income distribution can be grouped into five:

•personal tax changes, including the commitment to increasing the Income Tax personal allowance to £10,000

•decisions on how social security benefits should be adjusted from year to year, differing markedly between pensions and other benefits

•cuts and reforms to specific benefits

•continuing but adding to Labour’s pension reform programme

•merging six working-age benefits into Universal Credit.

Personal tax changes

The Income Tax allowance was increased in stages from £6,475 in 2010/11 to reach £10,600 by April 2015. Compared to adjustment in line with consumer price index (CPI) inflation, this was worth £700 per year for basic rate taxpayers, although adjustments to the higher rate threshold meant that the best-off taxpayers did not benefit from the increases (until the final year). At the same time, the extra ‘age allowance’ was phased out, so many pensioners gained little from these changes. From 2015/16 single-earner married couples are able to transfer £1,060 of an unused tax allowance to a spouse (worth £212 per year). NICs were increased in 2011/12, as planned by Labour. The coalition also retained the withdrawal of the personal allowance from those with incomes above £100,000, brought in some tighter limits on higher-rate pension contribution tax relief, and introduced changes that tapered away the value of Child Benefit from families containing an individual with annual taxable income of over £50,000. But from 2013/14, the 50% marginal rate on incomes above £150,000 inherited from Labour was cut to 45%.

Box 2.1: Benefits, pensions, tax credits and direct taxes policy timeline

Uprating benefits

As discussed above, a critical initial ‘non-decision’ of both Labour and the coalition was to continue uprating benefits in line with RPI inflation up to 2012/13. The effect was to shield some of the poorest initially from the effects of the 2008 financial crisis. What has happened since presents a marked contrast between pensions and other benefits. The basic pension (and the future amalgamated ‘single tier’ pension described below) is ‘triple-locked’. But for most working-age benefits, default indexation was switched to the CPI, rather than the RPI (or a related index). The CPI generally increases more slowly. And for three years from April 2013 working-age benefits were increased by only 1%, aiming to reduce their real value (although in the event, inflation was low in any case). The coalition agreed on a two-year cash freeze from April 2016. In the long term, benefit levels will be constrained by a new overall ‘welfare cap’, putting a cash limit on aggregate spending (excluding state pensions and Jobseeker’s Allowance). If the cost of or numbers receiving one benefit rise, spending will have to be cut elsewhere to keep within the cap.

Specific benefit and tax credit reforms

Specific benefit and tax credit reforms included:

•A cap of £26,000 a year on the total amount of benefits most working-age families could receive.

•Tighter limits on Housing Benefit for private tenants, and cuts for working-age social housing tenants deemed to have spare bedrooms (the so-called ‘bedroom tax’) (see Chapter Seven).

•Child Benefit was frozen in cash terms for three years from 2011/12, and then increased by 1% in 2014/15, representing a significant real terms cut. The ‘family element’ of Child Tax Credit was also frozen.

•Abolition of Labour’s Child Trust Funds from early 2011.

•Council Tax was frozen for most households, but Council Tax Benefit reforms meant many low-income households paying more or paying part of the tax for the first time.

•Reforms to tax credits (such as abolition of the extra ‘baby tax credit’ and a faster rate of withdrawal as income increased) made them less generous, although the ‘per child’ element was increased.

•Tighter conditions and tougher administration arrangements for disability and incapacity benefits. These were intended to reduce the overall spending, although this was not achieved, despite controversial effects as individual payments were cut or delayed (OBR, 2014, chart 4.5; Gaffney, 2015).

•Abolition of most of the Social Fund that gave emergency grants and loans to people with low incomes. Councils were given responsibility for organising local support, but with a lower budget.

•Stricter administration of many out-of-work benefits, including much greater...