eBook - ePub

Manga's Cultural Crossroads

Jaqueline Berndt, Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Jaqueline Berndt, Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer

This is a test

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Manga's Cultural Crossroads

Jaqueline Berndt, Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Jaqueline Berndt, Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Focusing on the art and literary form of manga, this volume examines the intercultural exchanges that have shaped manga during the twentieth century and how manga's culturalization is related to its globalization. Through contributions from leading scholars in the fields of comics and Japanese culture, it describes "manga culture" in two ways: as a fundamentally hybrid culture comprised of both subcultures and transcultures, and as an aesthetic culture which has eluded modernist notions of art, originality, and authorship. The latter is demonstrated in a special focus on the best-selling manga franchise, NARUTO.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Manga's Cultural Crossroads est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Manga's Cultural Crossroads par Jaqueline Berndt, Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Jaqueline Berndt, Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Literatura et Crítica literaria de cómics y novelas gráficas. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Manga

1 The View from North America

Manga as Late-Twentieth-Century Japonisme?

Frederik L. Schodt

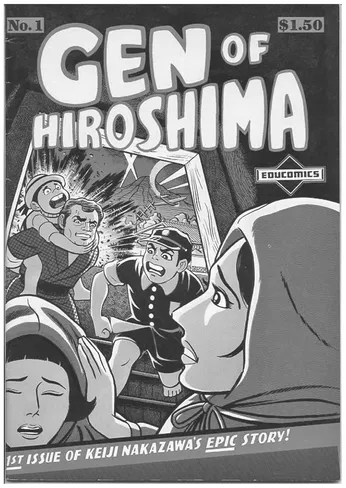

By my count, it has been more than thirty years since Japanese manga were first translated and published in North America. At first, they seemed rather like sushi did around that time, something so alien to the American palette they would never catch on. In 1980, a tiny San Francisco publisher named Educomics, run by Leonard Rifas, boldly ventured to issue part of Nakazawa Keiji’s long atom-bomb saga, Barefoot Gen, in American comic-book format ( Figure 1.1) . Rifas retitled it Gen of Hiroshima, broke the long (more than two thousand pages) story comics into short, forty-eight-page sections; flopped the pages images so they could be read left to right; and hand lettered the text in the style preferred by American readers. It was a commercial failure, ending after two issues. In 1982, Rifas published another, similar but shorter, work of Nakazawa’s called I Saw It, even colorizing it to further appeal to American tastes. While receiving good reviews, this, too, was a commercial failure. Nonetheless, these experiments set the stage for successes in 1987, when bigger publishers in San Francisco and Chicago issued more entertainment-oriented works such as Area 88, and Lone Wolf and Cub, also formatted in American comic-book style.

The change in the status of Japanese manga since 1980, not only in North America but also around the world, is quite breathtaking. Manga are now published in dozens of languages and have a global fan base of tens of millions of readers outside of Japan. What was once regarded by most people in Japan as something essentially unexportable has become an export commodity, especially when piggybacked on the global popularity of Japan’s more immediate and easily accessible entertainment medium—anime, manga’s younger sister. Most remarkably, in North America now, Japanese manga are usually read by English speakers in Japanese format. In other words, while translated, they are issued in Japanese page and panel order, read from right to left, in monochrome, with sound effects often still in Japanese, and usually issued in Japanese tankōbon, or book, style.

The elevated status of manga around the world in part reflects the unusual status of manga within Japan. In 1996, at the peak of the industry, the domestic market for manga was nearly saturated, and exports were one of the few areas where dramatic growth was possible. Manga represented

Figure 1.1 Cover of Gen of Hiroshima, illustrated by Peter Poplaski, Issue No. 1, 1980.

nearly 40% of all published magazines and books, and they were read by nearly all segments of society, with the possible exception of senior citizens. Even in 2009, sales of manga paperbacks alone still represented nearly 230 billion yen, or around US$2.7 billion.1 And nothing better represented the exalted position of manga and anime than the political campaign running up to national elections. That year, the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party still held on to its majority in parliament. The then-prime minister Aso Tar ō was a self-avowed otaku, or hard-core manga fan. With his encouragement, the government had begun to take an especially active role in supporting the anime and manga industries at home and in promoting manga and anime overseas, as part of a “Cool Japan” movement. Manga awards were established in the Foreign Ministry, cute young women called kawaii taishi (“ambassadors of cute”) were dispatched around the world as emissaries wearing anime-esque fashions, and there were plans to build a giant manga and anime museum in Tokyo. Moreover, in its campaign, the Liberal Democratic Party widely publicized a list of its top five campaign promises, and there—along with vows to oppose terrorism, protect the environment, and defeat the recession—was a vow to promote popular culture such as anime, games, and manga domestically and overseas. This emphasis on cartoons by a major political party was probably without parallel in modern politics. Unfortunately, for both the prime minister and his party, they lost.

Through no fault of the government, the manga market in Japan has also subsequently struggled. It is still gargantuan, but sales are down, especially for magazines. Japan is currently experiencing the double whammy of an unprecedented population decline and a rapidly aging society, due to a declining birthrate and longer life expectancy. This means that young people, the primary consumers of both manga and anime, are shrinking in both absolute and relative number as the population ages. There is also competition for their attention from Internet and manga cafes, from discounted secondhand stores, and from other forms of entertainment such as video games and especially the Internet. And Japanese publishers, slow to adapt to the Internet age and shielded to some extent from overseas trends, have been reluctant to embrace digital publications and thus take the steps necessary to ensure their own survival. As a result, today they face challenges not only from the normal digital piracy that has plagued publishers of manga and music and movies overseas, but also from a uniquely Japanese do-it-yourself phenomenon called jisui or “home cooking”. Manga series can run up to a hundred paperback volumes, and in crowded dwellings, owners of large collections often break up their books, scan the pages, and discard the originals, keeping only the digitized images to save space (and sometimes releasing these files onto the web, thus engaging in “piracy”). To the consternation of both publishers and artists, there are more and more businesses now also offering jisui as a service to customers.

Still, the problems manga have faced in Japan are nothing compared to what they have faced in North America, where I live. According to ICv2.com (which tracks pop culture and comics industry trends in North America), manga sales in the United States and Canada decreased 43% between 2007 (when they hit an estimated peak $210 million) and 2010 (when they plummeted to $120 million).2 Also, since 2007, there have been huge layoffs and reductions in manga lines at major publishers—Tokyopop went out of business, Bandai Entertainment and Del Rey stopped publishing manga, and Viz Media cut 40% of its staff. Sales of anime DVDs had already been in a steep slide for several years, but during the same period, the amount of anime being broadcast on television dropped precipitously. If the media around the world seemed somewhat confused by all this, it was no wonder. The implosion came just when manga and anime had seemed to be exploding in popularity and conquering the world. But after the manga and anime markets had been growing exponentially for years, that they would eventually hit a wall should have surprised no one, for with every boom there is usually a bust.

The reasons for the slowdown in the manga market in North America overlap only slightly with the reasons for the slowdown in Japan. In Japan, publishers lament that few artists have been able to come up with blockbuster hits, such as Kishimoto Masashi’s globally popular “Naruto”, Kubo Tite’s “Bleach”, or Oda Eiichirō’s “One Piece”, which have dominated sales in Japan for nearly a decade (“One Piece” alone is said to have sold more than 250 million paperback volumes in total, and in the last few years to have helped propped up the entire manga business). 3 This lack of new domestic hits obviously affects overseas markets, which are dependent on product from Japan. But far greater contributors to the sales slump in North America are the recession and the overall shift to digital content. Bookstores in the United States have declined rapidly in number, as more and more people purchase books through Internet stores such as Amazon or simply download e-books onto their electronic devices. And the effect on manga has been particularly huge and much greater than that on ordinary books or American comic books. When the giant bookstore chain Borders went out of business in 2011, it suddenly became hard for young people in many cities to even find manga, at least in a physical format, for at one point Borders had 642 stores and was said to have controlled 40% of all manga sales.4

Even more damaging to sales of manga in the United States has been rampant Internet piracy. The Internet and the World Wide Web are agnostic technologies that transmit any information that can be digitized, and they can be a force for both good and evil, at the same time. In the United States, Europe, and China, where the World Wide Web is more heavily used by highly computer-savvy manga and anime fans, the same technologies that have helped create “Cool Japan” are thus also helping to undermine it, by facilitating not only a diffusion of questionable material but also digital piracy. Partly because Japanese publishers have been so slow to adapt to the transition to a digital world, an entire generation of manga fans has become used to “scanlation”, wherein amateurs scan and translate manga on their own and then upload their work to file-sharing websites, where it can be enjoyed by others for free. From the scanlators’ perspective, they are performing an important service, helping to popularize works often unavailable in English, unknown, or too expensive, and works that often take too long for local publishers to license and issue in English. And there is truth in their argument, but it has also created a culture of expectation that manga should be free. Japanese publishers have recently attempted to cooperate and embrace the digital world, at least as it exists outside of Japan. But as ventures such as www.jcomics.com (which targets the North American market) have illustrated, they have not been extremely successful.

There are other, more subtle reasons for the manga slump in North America. I may be in a minority, but I believe there is also confusion among the public about what manga really are. In Japan, manga and anime are generic terms for what Americans loosely call comics (or cartoons) and animation, respectively. In North America, however, both manga and anime have until recently referred to comics and animation that are specifically from Japan. Yet what are Japanese comics and animation? True fans can extol the merits of both for hours and discuss how they prefer the Japanese-style story lines and characters over American-style works. They can also explain how they like the Japanese visual style. But to many North Americans, manga and anime are still defined only by a visual style—by big eyes, big bosoms, very young-looking female characters, and a cute quality not native to America. And this visual style is easily imitated, with the result that in neighborhood comics shops there are, in addition to shelves of translated Japanese manga, now sections of translated Chinese manhua and Korean manhwa, both of which are referred to by most people simply as manga. Making matters even more complicated, there are also now what are called OEL manga, or “original English-language” manga, created by English native speakers in a Japanese style. Anime has not yet become so confusingly diversified, but with the efforts that both China and Korea are currently putting into their own domestic industries, it soon will be.

The zeal of hard-core American otaku fans, who prize authenticity in manga format, has also led to a strange phenomenon. Because most Japanese manga are now published in English in Japanese format, with page and panel order in a right-to-left sequence, and onomatopoeia left in Japanese, they have in a sense become an awkward hybrid format. In Japan, the text on manga pages is read right-to-left, vertically; panels and images are also read right-to-left. Yet the Americanized versions of this are neither truly Japanese nor truly American, for they have text that is read left-to-right, horizontally, and images that are read right-to-left. In the minds of some readers, this presumably creates a certain cognitive dissonance. For mainstream readers whose only exposure is to American comic books or comic strips, having to learn to read translated manga “backwards”, or right-to-left, rather than left-to-right, must be off-putting, to say the least.

As manga and anime have become more mainstream, it should not be surprising that they also have faced more criticism in North America. In the early days, criticism was often leveled at fans, who were regarded as a tad weird, or immature, but there was scant scrutiny, at least on a serious level, given to what was actually being read or viewed. Today, both manga and anime are far more visible in society, and even if someone does not like manga or anime, that individual usually at l...