eBook - ePub

Strategies for Joint Venture Success (RLE International Business)

Peter Killing

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 4 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Strategies for Joint Venture Success (RLE International Business)

Peter Killing

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Although published thirty years ago this book accurately predicted that joint-ventures would become an increasingly prominent feature on the corporate landscape. This book, based on the experience of managers in both successful and unsuccessful joint ventures has been written expressly to help managers improve the performance of their joint ventures. It discusses the area of joint venture design and management including the management of ventures between corporations and government bodies.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Strategies for Joint Venture Success (RLE International Business) est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Strategies for Joint Venture Success (RLE International Business) par Peter Killing en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Negocios y empresa et Negocios internacionales. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1 THE JOINT VENTURE PARADOX

The paradox of joint ventures is simply stated. Although most managers heartily dislike joint ventures, they predict that they will be involved in more and more of them. Indeed, they have already been some startling bursts of activity, as in 1980 when China reportedly signed more than 300 joint venture agreements with foreign firms. Managers also expect that individual ventures are likely to be more important to their firms in the future than they have been in the past. Ventures like the joint engine and transmission plants of Volvo-Peugeot-Renault, and the 1980 Rolls-Royce venture with three Japanese firms to design and manufacture a jet engine for medium distance aircraft are endeavours that reach to the heart of these companies. Their success is critical to the firms involved, far more so than was typically the case with the traditional joint venture used to obtain a share of a growing market in the Third World or otherwise remote country. Peter Drucker has argued that joint ventures will become increasingly important and at the same time states that they are ‘the most difficult and demanding of all tools of diversification – and the least understood’.1 Few executives who have been closely involved with joint ventures would disagree.

The purpose of this book is to help European and North American managers to become more successful with joint ventures. It is based both on a review of existing studies and on a first-hand examination of 35 joint ventures located in North America and Western Europe and two in developing countries. In addition to making observations and conclusions based on interviews with joint venture general managers and executives in their parent companies, I have also written two sets of detailed case studies. Those in Chapter Three examine two joint ventures used to develop techniques for mining the seabed; and in Chapter Seven the failure of two German firms to use joint ventures successfully to exploit their technology in the US market is documented. One other source of information which I have drawn upon is the work of J.L. Schaan. Schaan is a doctoral student working under my direction who is currently completing a thesis which examines the techniques that local and foreign parent companies are using to control joint ventures in Mexico.2

In this chapter both sides of the joint venture paradox are examined. We begin with a look at the extent to which joint ventures are being used and the reasons why managers believe this usage rate is likely to increase. Later in the chapter the question of why joint ventures are difficult to manage is addressed – this being the reason why so many managers dislike joint ventures. The chapter ends with the question of whether or not some joint ventures are easier to manage than others.

Who is Using Joint Ventures?

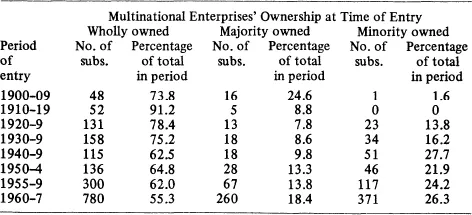

Although there is no complete listing of either joint ventures in existence or of those formed in any given year, it is apparent that many large companies are involved in at least one joint venture. The most recent survey of American firms was done by Alan Janger for the Conference Board and he reported that ‘most of the Fortune 500 companies and roughly 40% of industrial companies with more than $100 million sales are engaged in one or more international joint ventures. ’3 Janger’s findings are supported by data collected as part of Harvard University’s Multinational Enterprise Project, which indicated that as of 1967 only 33 of 187 major US multinational firms did not have at least one international joint venture.4 Between 1910 and 1967 there was a marked increase in the propensity of these 187 firms to use joint ventures, as the data in Table 1.1 indicate.

Table 1.1: Foreign Manufacturing Subsidiaries. Classified by Multinational Enterprises’ Ownership and Period of Entrya

Note: a. Excludes subsidiaries in Japan, Spain, Ceylon, India, Mexico, and Pakistan.

Source: J.M. Stopford and L. Wells, Managing the Multinational Enterprise, Table 10.1.

As an indicator of what the major firms of the world are doing, these American statistics most likely underestimate the extent to which joint ventures are being used. First, they exclude countries such as Japan in which joint ventures are demanded by the government. Secondly, American firms are generally considered to be less prone to form joint ventures than firms of other nationalities. One study observed, ‘Most of the American companies … generally resist joint ventures and go to great pains to avoid them … Those in European companies do not like joint ventures either … however they are markedly less fearful about dealing with “the natives” … and seem much more comfortable and able to roll with the punches … after they get in’.5 This observation is supported by the data in Table 1.2, which show that US firms use a lower percentage of joint ventures than firms from most other countries. This is particularly true in developing countries, where, for firms other than American and Swiss, joint ventures are the rule rather than the exception.6

To allow a closer look at the way in which joint ventures are being used in a specific industry, I have listed in Table 1.3 joint ventures formed in the automobile industry in a recent two-year period. This record has been compiled from quarterly listings provided by the journal Mergers and Acquisitions.7 As can be seen, 19 ventures were formed during the period, apparently for a wide variety of reasons. Quite a number included government agencies.

Why Use Joint Ventures?

There is not enough evidence available to determine whether or not the rate of joint venture formation is increasing. Janger reported that just over half of the 168 companies in his survey had formed new international joint ventures in the past five years. One third of the total group stated that their rate of international joint venture formation had increased in the past five years.8 Unfortunately, we do not know what was reported by the other two thirds. The Bureau of Economics of the US Federal Trade Commission does publish an annual listing of joint ventures formed involving American firms, but it is only based on what shows up in the press and other public sources Also, because the bureau has changed the definition of what it counts as a joint venture, an historical comparison is not possible. One other measure of joint venture formation is found in the listings provided by Mergers and Acquisitions,7 but as with the FTC listings, these are taken from public sources, are primarily American and probably ignore many of the small joint ventures which are formed each year. The number of joint venture formations involving American firms reported by this journal for selected years are shown in Table 1.4. These figures are not reliable enough to support detailed analysis, but generally they suggest that the number of new ventures formed annually by American firms has been constant since 1976, and that roughly one third of these are domestic ventures – formed in the US with US partners. The ventures from which my own sample is primarily taken are the 30–40 per cent of ventures which were formed in Western Europe (with local partners) or in North America with European partners.

Table 1.2: Percentage of Foreign Manufacturing Subsidiaries of Large Enterprises Based in Various Parent Countries which were Wholly Owned or Joint Ventures, 1 January 1971 (US data as of 1 January 1968)

Ownership Position: | ||||

National Base of Parent Enterprise | Wholly Owned Subsidiariesa | Majority Owned Joint Venturesb | Minority & 50–50 Joint Venturesc | Total Number of Subsidiaries Known |

In All Countries: | % | % | % | % |

United States | 63 | 15 | 22 | 3,720 |

United Kingdom | 61 | 19 | 20 | 2,236 |

Japan | 9 | 9 | 82 | 445 |

France | 24 | 29 | 47 | 333 |

Germany | 42 | 28 | 30 | 753 |

Italy | 42 | 24 | 35 | 106 |

Belgium & Luxembourg | 37 | 34 | 29 | 184 |

Netherlands | 61 | 18 | 20 | 401 |

Sweden | 64 | 17 | 19 | 155 |

Switzerland | 59 | 29 | 19 | 292 |

In Less Developed Countries:d | ||||

United States | 57 | 19 | 24 | 1,583 |

France | 11 | 37 | 52 | 157 |

Germany | 44 | 31 | 25 | 323 |

Italy | 33 | 25 | 45 | 67 |

Belgium & Luxembourg | 21 | 51 | 28 | 39 |

Netherlands | 33 | 28 | 39 | 82 |

Sweden | 39 | 32 | 29 | 44 |

Switzerland | 54 | 33 | 26 | 84 |

Notes: a Owned 95% or more by a foreign parent. b. Owned more than 50% but less than 95% by a...