![]()

Part I

COLLAPSE

![]()

1

THE SUCCESSION OF EMPERORS

One of the main problems with the Roman empire was its incessant changes of emperor. The succession to the throne had never been effectively worked out, but now things were much worse, since the army often proceeded to kill the reigning emperor (see Figures 1 and 2) and appoint his successor, who was also killed not very long afterwards.1

Typical of this situation, in many ways, was the frightening emperor Maximinus I (235–238). Julius Verus Maximinus, Gaius, also known as Maximinus Thrax (‘the Thracian’), a Danubian of relatively humble stock, exploited the opportunities of the Severan army to gain numerous senior appointments. He became emperor by chance at Mainz (Moguntiacum, March 235) in the mutiny against … Severus Alexander.

An equestrian outside the ruling clique, he was unsure of his position. He attempted to conciliate the senate from afar, remaining on the frontier with his troops and attempting to act the successful warrior–emperor; he campaigned vigorously over the Rhine and Danube. However, his overtures were unwelcome, his absence from Rome politically unwise, and his wars expensive. The revolt of Gordian I recalled him to Italy, where he then faced Balbinus and Pupienus. The stubborn resistance of Aquileia caused Maximinus to lose his judgment, and the military initiative. His troops became disheartened with the lack of progress and finally murdered him and his son (spring 238).2

Here is more about Gordian I, who unsuccessfully revolted against Maximinus I.

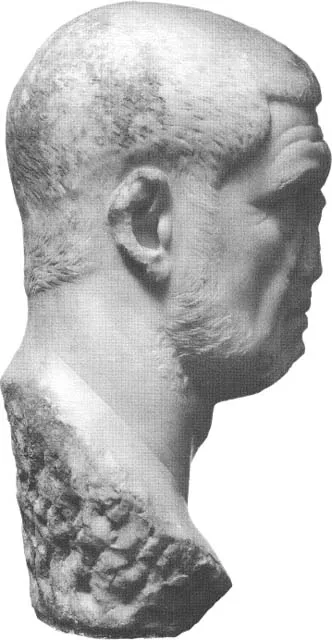

Figure 1 Bust of Maximinus I Thrax (235–8) (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Denmark).

Figure 2 Coin of Pupienus. (Photograph courtesy of Michael Grant)

Gordian I (Marcus Antonius Sempronius Romanus), Roman emperor AD 238. An elderly proconsul of Africa, he intervened in a plot against Maximinus I, only to find himself proclaimed emperor. He made his son, Gordian II, his colleague. The senate, also hostile to Maximinus, quickly acknowledged them.

However, the rebels were militarily weak, and when Capel[l]ianus, governor of Numidia, moved against them with his legionary army, Gordian II was killed and Gordian I committed suicide, after a reign of only a few weeks (early 238).3 The senate, compromised, continued the insurrection under Balbinus and Pupienus.

Balbinus (Decius Caelius Calvinus) and Pupienus (Marcus Clodius Maximus), members of a board of twenty consulares appointed by the senate for the defence of Italy against the emperor Maximinus, were after the deaths of Gordian I and II chosen joint emperors by the senate (AD 238). Both had had long senatorial careers. Constitutionally, on the model of the consulate, they had equal powers, each being pontifex maximus, but Balbinus was entrusted with the civil administration and Pupienus with the command of the army. To placate the people, the boy Gordian III was given the status of Caesar. At the news of Maximinus’s murder Pupienus proceeded to Aquileia and sent back the former’s legions to their provinces, and with his bodyguard returned to Rome to share a Triumph with Balbinus and Gordian.

For a few days the government worked smoothly, but the praetorians, who resented the senate’s action, mutinied. The two emperors were dragged from their palace and murdered after reigning for three months.4

Gordian III was their successor (see Figure 3), but he was very young, the conduct of affairs being for the most part in the hands of Timesitheus, whose subsequent death laid the empire wide open. But Gordian III, unlike almost every other emperor of the period, was not murdered but died (at Zaitha), perhaps of wounds. His rulership had been largely ineffective. Here is a more detailed account of his reign:

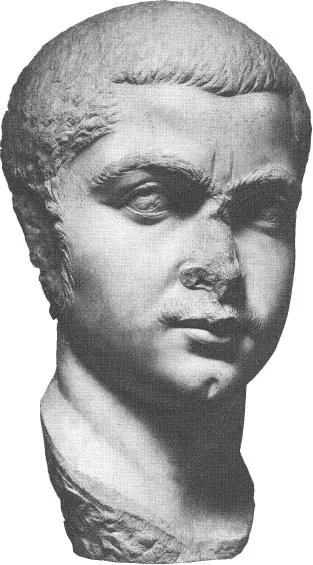

Figure 3 Bust of Gordian III (238–44) (Museo delle Terme, Rome. Archivi Alinari/Anderson).

Gordian III (Marcus Antonius Gordianus), grandson of Gordian I by a daughter, was forced on Balbinus and Pupienus as their Caesar and after their murder (mid-AD 238) saluted emperor by the praetorians at the age of 13.

The conduct of affairs was at first in the hands of his backers but, as fiscal and military difficulties increased, it passed to the praetorian prefect Gaius Furius Sabinius Aquila Timesitheus (241). Timesitheus prepared a major campaign against Persia which, beginning in 242, achieved substantial success before his death, by illness, in 243. Gordian replaced Timesitheus with one of the latter’s protégés, Marcus Julius Philippus, who continued the war. However, the Roman army suffered defeat near Ctesiphon [Kut], and shortly afterwards Gordian died (early 244). He was succeeded by Philippus.

Though the period of the Gordians shows some of the characteristics of the third-century ‘crisis’, it is best interpreted as a reversion to the Severan monarchy after the aberrance of Maximinus.5

Philip, his successor, was not a Roman or Italian. Here are some further particulars about him (see Figure 4).

Philip (Marcus Julius Philippus), Roman emperor AD 244–9. An Arabian from Shahba (SE of Damascus), he became praetorian prefect of Gordian III and, early in 244, succeeded him as emperor.

After making peace with Persia, he immediately went to Rome. His reign saw the thousandth anniversary of the city (247–8), and the beginning of the third century ‘crisis’ proper, characterised by invasion over the Danube and Roman civil war. Philippus repelled the Carpi (245–7), but left Pacatian’s rebellion … to Decius (248–9). Decius’ troops proclaimed him emperor in summer 249, and in the autumn he defeated and killed Philippus at Verona.6

Philip had ruled for five years, but his reign had been neither peaceful nor useful. No better was that of his successor Decius (see Figure 5), whose emperorship lasted for two years.

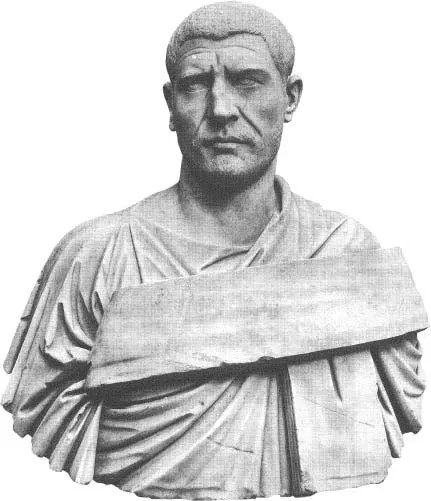

Figure 4 Bust of Philip (244–9) (Museo Vaticano, Rome. Archivi Alinari/Anderson).

Decius (Gaius Messius Quintus), emperor 249–251, born in Pannonia, but of an old senatorial family, had already achieved high office before being appointed by Philip to restore order on the Danube. His success, and Philip’s unpopularity, caused his troops to declare him emperor and compel them to overthrow his patron.

In 250 the Carpi invaded Dacia, the Goths, under Kniva, Moesia. Decius was defeated near Beroea [Verria]. The following year, in an attempt to intercept the Goths on their way home, he and his son Herennius [Etruscus] were defeated and killed at Abrittus [near Razgrad].

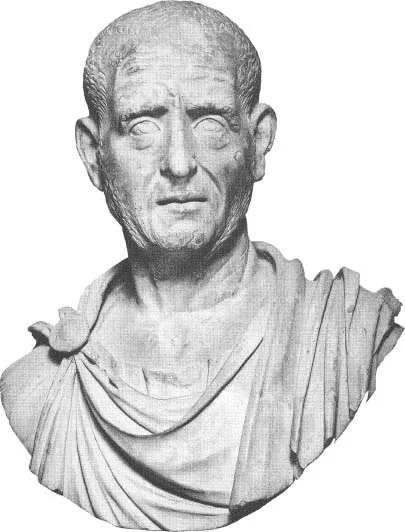

Figure 5 Bust of Decius (249–51) (Museo Capitolino, Rome. Archivi Alinari/Anderson).

Decius was a staunch upholder of the old Roman traditions. His assumption of the additional surname of Trajan promised an aggressive frontier policy, and his persecution of Christians resulted from his belief that the restoration of state cults was essential to the preservation of the empire … However, his approach was outdated, and his reign initiated the worst period of the third century ‘crisis’.7

Decius’s death at Abrittus, at the hand of the Goths, was a unique feature, as this was the one and only occasion when a Roman emperor was slain by an enemy. It marked a very low point in the history of the Roman empire. The successor of the slain emperor was Trebonianus Gallus (see Figure 6).

Trebonianus Gallus (Gaius Vibius) ruled AD 251–3. A successful senatorial governor of Moesia, he was acclaimed by the army immediately after Decius’ death.

He made an unfavourable peace with the Goths, then returned to Rome, where he adopted Decius’ young son [his second, Hostilianus]…. Perhaps distracted by the effects of a severe plague, he appeared to ignore renewed Persian aggression (including the capture of Antioch), and failed even to return to the Danube to avenge his predecessor (whose end he was suspected of having contrived). When the Danubian troops forced Aemilian’s usurpation in 253 (early summer), Gallus sent Valerian to gather reinforcements, but he was killed at Interamna Nahars [Terni] by his own men before these could arrive (late summer).8

Figure 6 Medallion of Trebonianus Gallus. (Photograph courtesy of Michael Grant).

The reign of Trebonianus Gallus was a period of unmitigated disaster, accentuated by plague and famine. One can now see the imperial rulership at its worst: in the hands of a soldier, who proved inadequate and unsuccessful. Of his short-lived successor Aemilian (see Figure 7), the following has been said:

Aemilian (Aemilius Aemilianus, Marcus), emperor AD 253. Against imperial policy, while governor of Moesia, he dealt harshly with the Goths, and was proclaimed emperor by the army.

He marched on Italy, overthrew Trebonianus Gallus, but was soon killed by his own troops, panicked by the approach of Valerian. The civil strife of 253 exposed Greece to Gothic invasion.9

Aemilian had only lasted a very short time. He was typical of the military men who now, without much success, aspired to rule the empire. His successor was Valerian (see Figure 8), who reigned much longer, but came to a disastrous end:

Valerian (Publius Licinius Valerianus), ruled AD 253–60. An elderly (in his 60s) noble senator of great experience, he was sent to Raetia to gather troops to help Trebonianus Gallus against Aemilius Aemilianus. On the death of Gallus, he was hailed as emperor by his men, and marched on Italy. Following the murder of Aemilianus, Valerian and his adult son Gallienus were universally recognised as Augusti. Both strove to serve the empire in circumstances that, as growing external pressures exacerbated internal economic, political and moral w...