eBook - ePub

Women and Children First (Routledge Revivals)

International Maternal and Infant Welfare, 1870-1945

Valerie Fildes, Lara Marks, Hilary Marland, Valerie Fildes, Lara Marks, Hilary Marland

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Women and Children First (Routledge Revivals)

International Maternal and Infant Welfare, 1870-1945

Valerie Fildes, Lara Marks, Hilary Marland, Valerie Fildes, Lara Marks, Hilary Marland

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

First published in 1992, this book explores the efforts to counteract the high maternal and infant death rates present between the end of the nineteenth century and the Second World War. It looks at the problem in five different continents and shows the varying approaches used by the governments, institutions and individuals in those countries. Contributors display how policy and practice have been shaped by the structure of maternity services, nationalism, the conflict of colonization and cultural factors. In doing so, they illustrate how welfare policy and funding were moulded throughout the world in the times considered.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Women and Children First (Routledge Revivals) est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Women and Children First (Routledge Revivals) par Valerie Fildes, Lara Marks, Hilary Marland, Valerie Fildes, Lara Marks, Hilary Marland en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Historia et Historia del siglo XIX. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1

Some international features of maternal mortality, 1880–1950

Maternal mortality was the great exception in what has been called the great mortality decline. From the end of the nineteenth century until the mid-1930s, when death rates in general and infant mortality in particular were steadily declining, maternal mortality scarcely altered. In England and Wales the maternal mortality rate (henceforth MMR) was 44.4 in 1867, 44.1 in 1898 and 44.2 in 1934.1 When babies were born in Britain in or before the mid-1930s, the risk of their mothers dying in childbirth, regardless of social class, was essentially as high as it would have been had they been born in a mansion, a middle-class house or a working-class tenement when Queen Victoria was still a young woman.2 Maternal mortality had remained on a high plateau for the best part of a century until, in the mid-1930s, it started to decline steeply and continuously. By 1980 the MMR was only one fiftieth of the rate in 1934. This is an extraordinary demographic story which raises many questions.

First, why did maternal mortality fail to decline until the mid-1930s? Second, what factors led to the sudden and profound fall just before the Second World War? (I will postpone the answer to this question until the end of this chapter.) Third, was the trend I have described confined to Britain or was it seen in other countries? Fourth, during the period of high maternal mortality, was the average MMR much the same in all western countries or were there wide differences?

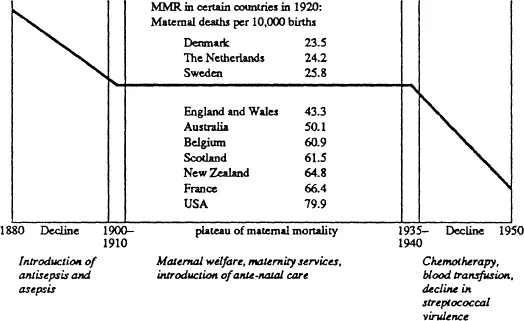

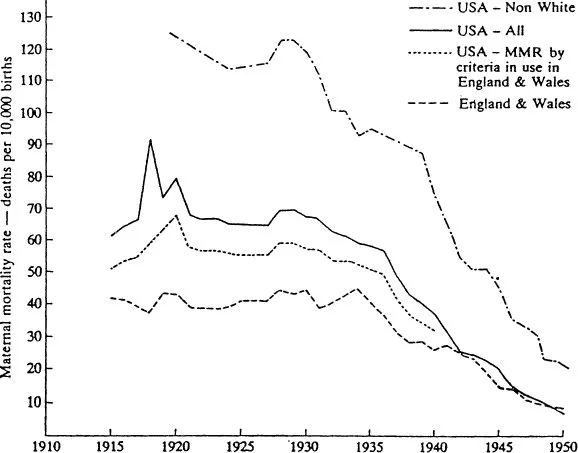

Let us take the last two questions first. Figure 1.1 is a schematic representation of the trend in maternal mortality in western countries from 1880 to 1950 which also shows the MMR in 1920 in various countries. One can see that between 1900 and the mid-1930s the safest countries to have a baby were, by a very large margin, the Netherlands and Scandinavia; the most dangerous was the USA followed by France, New Zealand and Scotland. England and Wales came in the middle. The risk of dying in childbirth for American mothers in the 1920s was about three times as high as the risk for Dutch or Danish mothers, and for non-white mothers in the USA it was at least five times as high.

Figure 1.1 Schematic representation of the pattern of maternal mortality seen in most developed countries, 1880–1950, together with the maternal mortality rates of certain countries in 1920

Source: R.M. Woodbury, Maternal Mortality. The Risk of Death in Childbirth and from all the Deseases caused by Pregnancy and confinement (Washington, DC, 1926), supplemented by published vital statistics of various countries.

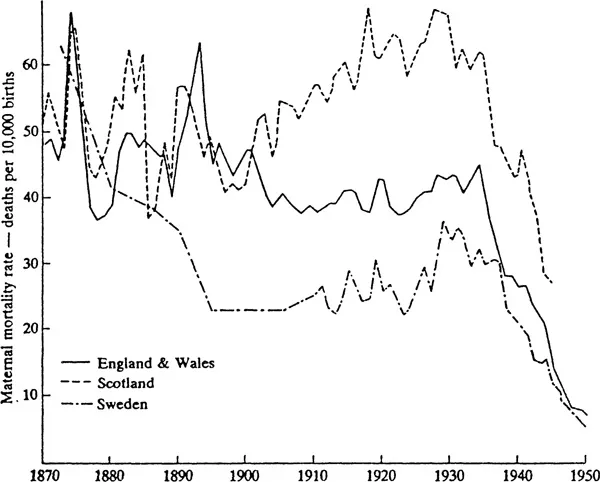

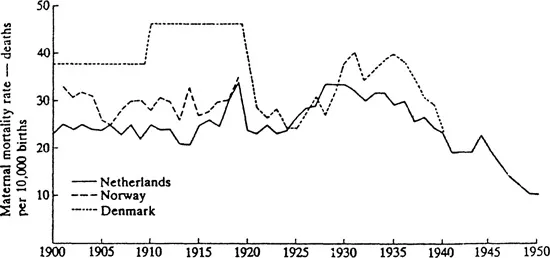

Figures 1.2 to 1.5 show the trend in the annual rates of maternal mortality in various countries. While they show that broadly speaking the plateau of maternal mortality and the post-1935 decline were common throughout the western world, they also show that the plateau was not completely flat. Between 1880 and 1910 there was a decline in maternal mortality which was steep in some countries such as Scandinavia and the Netherlands (and also as it happens Massachusetts) but slight in others such as England and Wales. From 1910 to 1935, however, this was reversed, and we find a rising trend in maternal mortality, the gradient being gentle in England and Wales, but quite steep in Scotland, Sweden and Denmark.3

Figure 1.2 Maternal mortality, 1870–1950, England and Wales, Scotland and Sweden

Sources: See Table 1.1.

Figure 1.3 Maternal mortality, 1900–1950, the Netherlands, Norway, and Denmark

Sources: See Table 1.1.

Note: Denmark, 1900–9 (towns only), 1910–19 (whole country); annual statistics available from 1922 (whole country).

Figure 1.4 Maternal mortality, 1915–1950, USA and England and Wales

Sources: See Table 1.1.

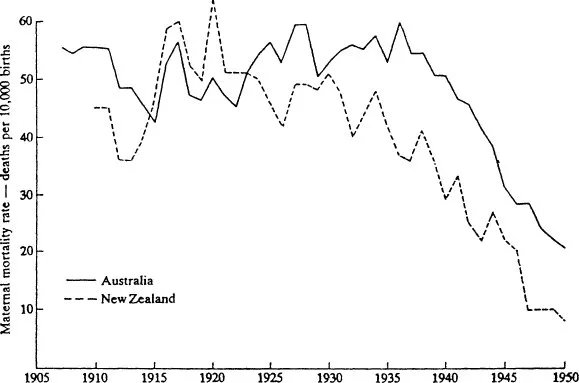

Figure 1.5 Maternal mortality, 1905–1950, Australia and New Zealand

Sources: See Table 1.1.

We can now return to the first question: why did maternal mortality remain on a high plateau until the mid-1930s? Were the reasons primarily clinical, or were they social and economic, or a combination of both? If anyone or anything was to blame for the sustained high level of mortality was it the health of mothers and their living conditions, the indolence or indifference of government, or was it the standard and availability of obstetric care provided by midwives (trained and untrained), general practitioners, specialist obstetricians and maternity hospitals? And if we find (as we will) that it was a combination of many factors, how much weight do we give to each in different countries at different periods? Before we attempt to answer these questions we must appreciate the impact of maternal mortality on the public, the medical profession and health authorities.

Maternal mortality as a major problem

The decline in maternal mortality between 1880 and 1910, which was associated with the introduction of antisepsis and asepsis into midwifery, was accompanied by a transformation of hospital mortality. Before 1880 maternal mortality in lying-in hospitals all over the world had been horrific, sometimes reaching levels of 400 per 10,000 births or about ten times the rate in home deliveries. The cause of the terrible mortality before the 1880s was puerperal fever and there was even talk of closing down all lying-in hospitals. By 1910, however, hospital mortality had often fallen so steeply that the MMR was usually lower than it was for home deliveries, even though hospitals had an excess of complicated cases and emergency admissions.

Thus, at the Rotunda Hospital in Dublin, 2,060 women were delivered in 1907–8 and only three died from sepsis. At the York Road Lying-in Hospital in London over a period of 16 years in the early part of this century, 8,373 deliveries were carried out without a single death from infection. In Basle, Professor 0. von Herff reported in 1907 that 6,000 deliveries had taken place without a single death from sepsis.4 In Australia the Sydney Women’s Hospital reported ten years’ work in 1904 with 4,000 cases and not a single death from puerperal sepsis, and the Australian Committee on Maternal Mortality stated boldly in 1917 that

Puerperal septicaemia is probably the gravest reproach which any civilised nation can by its own negligence offer to itself. It can be prevented by a degree of care which is not excessive or meticulous, requiring only ordinary intelligence and some careful training. It has been abolished in hospitals and it should cease to exist in the community. It should be as rare as sepsis after a surgical operation’.5

This transformation of maternity hospital mortality was so encouraging that people concerned with maternal care in the first decade of this century were confident maternal mortality would soon be conquered. It was only a question of bringing home deliveries into line with hospitals. One can appreciate their horror when, year after year, they saw what they never expected to see: a relentless rise in maternal deaths. To make matters worse, it was soon recognized that a large proportion of maternal deaths was preventable but not prevented. Hundreds, if not thousands of women were dying unnecessarily, leaving devastated families: husbands without wives, babies and young children without mothers and a continuous stream of miserable recruits for the orphanages. Maternal mortality was a scandal.

So it was that during the second and third decades of this century action was demanded. Maternal mortality committees and associations were established, some medical and some lay, and numerous investigations of maternal care were carried out. Governments passed Acts and funds were obtained from states or charities to establish clinics, increase the number of maternity beds, and provide additional medical personnel.6 No one doubted the need for reform, and few doubted reforms would be successful. But different policies were adopted. Britain supported a broad portfolio of policies with better obstetric education heading the list. The Midwives Act of 1902 was followed by other Acts to regulate midwives and make trained care more widely available, notably the Midwives Act of 1936. The Royal College of Obstetricians was founded in 1929 and stimulated an increase in the number of consultant obstetricians whose job it would be to deal with complicated cases, to teach and to advise. But the backbone of British obstetrics remained for the time being the midwife and general practitioner delivering patients in their homes.7

In the USA it was believed that maternal mortality would only be defeated when hospital delivery by specialist obstetricians was the rule and delivery by the midwife and general practitioner obstetrician was abolished. After the First World War obstetricians and government were united in moving towards that goal as rapidly as possible. The Netherlands took the opposite view. The great bulk of deliveries took place at home attended by highly trained midwives, backed up by hospital care for complicated cases. New Zealand moved more rapidly towards hospital delivery than even the United States, but it believed in the midwife and retained her for hospital deliveries.8 Everyone talked about obstetrics as a branch of preventive medicine and expressed their faith in antenatal (prenatal) clinics and health education. Yet, by the harsh evidence of the statistics, none of these measures was effective. This brings us back to the puzzle of the plateau and thus to the immediate causes of maternal mortality.

The causes of maternal mortality: sepsis and abortion

From the mid-nineteenth c...