eBook - ePub

The Apple and the Spectroscope (Routledge Revivals)

Being Lectures on Poetry Designed (in the main) for Science Students

T R Henn

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

The Apple and the Spectroscope (Routledge Revivals)

Being Lectures on Poetry Designed (in the main) for Science Students

T R Henn

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

First published in 1951, this book is based on a course of lectures on poetry and prose given at Cambridge University during the long vacations of 1946-1950. A request for lectures of this kind came originally from a group of science students and the response was such that a course of this nature ran yearly. The purpose was to provide students from disciplines other than the humanities with the opportunity to feed their interest in English poetry and literature.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que The Apple and the Spectroscope (Routledge Revivals) est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à The Apple and the Spectroscope (Routledge Revivals) par T R Henn en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Letteratura et Critica letteraria. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Chapter I

Some Considerations on the Methods of Poetry

MY object in these lectures is to offer some suggestions regarding the mechanisms and technique of poetry. I shall illustrate them by certain arbitrarily chosen examples, which (in view of the difficulty of bringing in books) I have had printed for you. We shall consider two or three of these poems at each lecture. I do not think you should take notes; at the end of the little booklet is a blank half-sheet for possible definitions, and you can if you like scribble rough notes in the margins of the poems themselves.

These poems are chosen to suggest to you, as far as possible, the application of poetry to life; that is, they each deal with one or more attitudes to life, which I shall try to analyse as we come to them. And for the moment I am taking Dr. Johnson’s phrase: “What should books teach but the art of living ?” as a kind of reference point. We shall try to see later what that phrase may mean to-day: and afterwards, perhaps, what Matthew Arnold meant by his phrase: “Poetry is a criticism of life.”

To start with, then, we can consider the components of a poem. These are, very roughly, Diction and Rhythm. Words are set in a certain pattern or organization. These patterns will have normally a recurrent quality: hence versus (returning) for verse, just as prosus (straight on) for prose. To denote this pattern we shall use the symbol P.

Rhythm is usually organised as metre, ‘sections of rhythm’ It comprises stress, tone, and pitch. It is, for our purposes, a quality which produces the impression of a proportion between the events, or groups of events of which a sound sequence is composed.1 Note the word ‘impression’; we tend to hear rhythm in any repeating sequence, such as the beat of wheels in a train, without necessarily demanding an exact mathematical relationship between its components.

We know comparatively little about the psycho-physiological effects of rhythm. Changes that occur in response to it may include a variation in the pulse-rate, and even a change in the chemical composition of the blood. For our purposes, however, we can regard it as having some or all of the following effects upon us:

(a) a stimulus to increased awareness and receptivity.

(b) the imposition of a pattern upon a complex fusion of thought and emotion.

(c) a kind of ‘charging’ of words with a greater potential of meaning or meanings.

Diction we can consider under two headings:

(a) the organization of words into this rhythmical pattern, P.

(b) the use of words for the purpose of imagery: that is the establishment of relationships between two objects or ideas, and the consequent suggestion of their related values.

This last is such an important aspect of poetry that we must consider it in some detail. We can deal with it first under two simple headings, Simile and Metaphor: the first a comparison introduced by like or as, the second a direct identification.

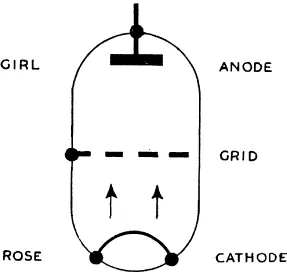

Now consider what occurs in our normal methods of using imagery. When Burns says “My love is like a red red rose,” the image is so hackneyed that we tend to forget what the first poet who made that comparison may have had in mind. The duplicated red merely means that the rose is intensely, or perhaps, ‘valuably’ red. If we look at the problem in terms of a valve, we have the girl and the rose represented by anode and cathode respectively. What in fact has happened is that certain particles of meaning have streamed across from the rose and attached themselves to the girl. Some of these are: colour, texture, perfection of a short-lived maturity, and the passionate colour

red—for blood, royalty, dignity. But it is apparent that there is also a kind of screen or suppressor in the intervening space, a screen that lets certain kinds of particles pass through, and stops others: and this screening function will depend on the context of the poem, and on the conventions of the poet and his age. When Herrick says

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may

he is exploiting one kind of significance only: the thought of the rosebud opening as virginity passes to womanhood. When George Herbert writes of it:

Sweet rose, whose hue angrie and brave

Bids the rash gazer wipe his eye :

Thy root is ever in its grave,

And thou must die.

—he is bringing together the two thoughts of admiration and death. When the Elizabethan poet speaks perpetually of the eating canker at the heart of the rose as a symbol of corrupted or corruptible womanhood, he is doing something different from, and much less complicated than, the thing that Blake is trying to express in the little poem on your sheet, The Sick Rose.

As a further example of the ‘conventional’ screening, consider the simple simile The man was as brave as a Hon. It is clear that we have allowed to pass over from lion to man certain conventional attributes of the heraldic lion: the king of beasts, courage, ferocity, and so forth. We have shut off by our screen the lion’s cowardliness, his mange, his parasites. The same sort of process goes on continually; but many of the images in common use we accept so superficially and rapidly that we scarcely think of their implications, of their history, or of the significance they had when the image was first struck out.

Now if we use another electrical figure for the working of a metaphor, that of a spark jumping a gap (and providing a sudden illumination), the width of the gap will vary with different images. Our man-lion comparison involved a smaller gap than the girl-rose. But the gap may be of any width: provided only that a spark can be forced across it. So when Edith Sitwell writes:

The light is braying like an ass

she is attempting to produce an impression of a stridency, or harshness, in the quality of the light. When Eliot writes:

I am aware of the damp souls of housemaids

Sprouting despondently at area gates

the same process is at work; the gap is wider, the voltage of the imagination required to bridge the gap is greater.

Now the electrical simile for this sparking across the gap can be taken a stage further. The ‘normal’ voltage of our imagination is always, to some extent, present; the gap is bridged with ease, provided it is narrow, or has been narrowed by convention or usage; but if it is wide, or unusual, a greater voltage must be produced, by some means or other, if the reader is to receive the image. That voltage may be thought of as generated in some or all of the following ways:

(a) By the excitement produced in, and by, the poem itself. (We have noted already the stimulus effect of rhythm.)

(b) By the poet’s usage: that is, by the manner in which he accustoms us to his way of thinking in relation to images.

(c) By the historical tradition in which he is working, and which we can understand by a study of his time.

We shall see later on examples of all these ways of bridging the spark gap, of making the images acceptable.

So far we have dealt with ‘simple’ images, simile or metaphor. We can carry them a stage further. In making comparisons of this kind, we are really attempting

(a) to synthesize certain aspects of two disparates to form a third, and/or

(b) to draw together the resources of different kinds of meaning to form a third kind of meaning, which is expressible in no other way.

We shall consider examples at a later stage.

For this is the final justification of all poetry: that it seeks to express a peculiar fusion of ideas and emotions which are normally on the edge of consciousness, or even beyond it. We have seen that its rhythmic structure produces an increased awareness, an excitement both emotional and intellectual By means of imagery it is expressing a particular kind of synthesis of meaning, perhaps best suggested in terms of a moving point, ‘T’, perceived in a three-dimensional field (one dimension being the emotional stimulus or ‘potential’ excited by the form), and related to two reference points, ‘O’ and ‘I’, which may be regarded (for the purposes of this illustration) as being stable. The third dimension would be represented by certain subjective values given to both object and image by the reader himself.

Now with this in mind, we can distinguish several kinds of imagery with which we shall be concerned. There is first what we may call traditional imagery; which we often accept carelessly, because we are so accustomed to it. Its roots may be in the Bible, or Homer, or Plato, or Shakespeare. There are instances by the hundred: the hart desiring the water brooks, the valley of the shadow of death,2 the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, the group of images that compare the spirit to a bird; and so on. Of them I would only suggest at this stage that all of them are well worth looking into, to see what lies beneath that easily-accepted surface.

Then there is the matter of personal imagery; the peculiar choice that a poet may exercise because of his own experience, his special reading, and the like. Whether that proves acceptable to us or not depends on how convincing he can make it, and how far we come to meet him. The scientific imagery that we shall see at work in Donne is part-personal, part-historical; but it requires from us an understanding of his background and hi...