![]()

Part I

Returns and Earnings

![]()

An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers

Ray Ball* and Philip Brown†

Accounting theorists have generally evaluated the usefulness of accounting practices by the extent of their agreement with a particular analytic model. The model may consist of only a few assertions or it may be a rigorously developed argument. In each case, the method of evaluation has been to compare existing practices with the more preferable practices implied by the model or with some standard which the model implies all practices should possess. The shortcoming of this method is that it ignores a significant source of knowledge of the world, namely, the extent to which the predictions of the model conform to observed behavior.

It is not enough to defend an analytical inquiry on the basis that its assumptions are empirically supportable, for how is one to know that a theory embraces all of the relevant supportable assumptions? And how does one explain the predictive powers of propositions which are based on unverifiable assumptions such as the maximization of utility functions? Further, how is one to resolve differences between propositions which arise from considering different aspects of the world?

The limitations of a completely analytical approach to usefulness are illustrated by the argument that income numbers cannot be defined substantively, that they lack “meaning” and are therefore of doubtful utility.1 The argument stems in part from the patchwork development of accounting practices to meet new situations as they arise. Accountants have had to deal with consolidations, leases, mergers, research and development, price-level changes, and taxation charges, to name just a few problem areas. Because accounting lacks an all-embracing theoretical framework, dissimilarities in practices have evolved. As a consequence, net income is an aggregate of components which are not homogeneous. It is thus alleged to be a “meaningless” figure, not unlike the difference between twenty-seven tables and eight chairs. Under this view, net income can be defined only as the result of the application of a set of procedures {X1, X2, … } to a set of events {Y1, Y2, … } with no other definitive substantive meaning at all. Canning observes:

What is set out as a measure of net income can never be supposed to be a fact in any sense at all except that it is the figure that results when the accountant has finished applying the procedures which he adopts.2

The value of analytical attempts to develop measurements capable of definitive interpretation is not at issue. What is at issue is the fact that an analytical model does not itself assess the significance of departures from its implied measurements. Hence it is dangerous to conclude, in the absence of further empirical testing, that a lack of substantive meaning implies a lack of utility.

An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers requires agreement as to what real-world outcome constitutes an appropriate test of usefulness. Because net income is a number of particular interest to investors, the outcome we use as a predictive criterion is the investment decision as it is reflected in security prices.3 Both the content and the timing of existing annual net income numbers will be evaluated since usefulness could be impaired by deficiencies in either.

An Empirical Test

Recent developments in capital theory provide justification for selecting the behavior of security prices as an operational test of usefulness. An impressive body of theory supports the proposition that capital markets are both efficient and unbiased in that if information is useful in forming capital asset prices, then the market will adjust asset prices to that information quickly and without leaving any opportunity for further abnormal gain.4 If, as the evidence indicates, security prices do in fact adjust rapidly to new information as it becomes available, then changes in security prices will refleet the flow of information to the market.5 An observed revision of stock prices associated with the release of the income report would thus provide evidence that the information reflected in income numbers is useful.

Our method of relating accounting income to stock prices builds on this theory and evidence by focusing on the information which is unique to a particular firm.6 Specifically, we construct two alternative models of what the market expects income to be and then investigate the market’s reactions when its expectations prove false.

Expected and Unexpected Income Changes

Historically, the incomes of firms have tended to move together. One study found that about half of the variability in the level of an average firm’s earnings per share (EPS) could be associated with economy-wide effects.7 In fight of this evidence, at least part of the change in a firm’s income from one year to the next is to be expected. If, in prior years, the income of a firm has been related to the incomes of other firms in a particular way, then knowledge of that past relation, together with a knowledge of the incomes of those other firms for the present year, yields a conditional expectation for the present income of the firm. Thus, apart from confirmation effects, the amount of new information conveyed by the present income number can be approximated by the difference between the actual change in income and its conditional expectation.

But not all of this difference is necessarily new information. Some changes in income result from financing and other policy decisions made by the firm. We assume that, to a first approximation, such changes are reflected in the average change in income through time.

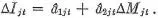

Since the impacts of these two components of change—economy-wide and policy effects—are felt simultaneously, the relationship must be estimated jointly. The statistical specification we adopt is first to estimate, by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), the coefficients (a1jt, a2jt) from the linear regression of the change in firm j’s income (∆Ij,t−τ) on the change in the average income of all firms (other than firm j) in the market (∆Mj,t−τ)8 using data up to the end of the previous year (τ = 1,2, … , t − 1) :

where the hats denote estimates. The expected income change for firm j in year t is then given by the regression prediction using the change in the average income for the market in year t:

The unexpected income change, or forecast error (ûjt), is the actual income change minus expected:

It is this forecast error which we assume to be the new information conveyed by the present income number

The Market’s Reaction

It has also been demonstrated that stock prices, and therefore rates of return from holding stocks, tend to move together. In one study,9 it was estimated that about 30 to 40 per cent of the variability in a stock’s monthly rate of return over the period March, 1944 through December, 1960 could be associated with market-wide effects. Market-wide variations in stock returns are triggered by the release of information which concerns all firms. Since we are evaluating the income report as it relates to the individual firm, its contents and timing should be assessed relative to changes in the rate of return on the firm’s stocks net of market-wide effects.

The impact of market-wide information on the monthly rate of return from investing one dollar in the stock of firm j may be estimated by its predicted value from the linear regression of the monthly price relatives of firm j’s common stock10 on a market index of returns:11

where PRjm is the monthly price relative for firm j and month m, L is the link relative of Fisher’s “Combination Investment Performance Index” [Fisher (1966)], and vjm is the stock return residual for firm j in month m. The value of [Lm − 1] is an estimate of the market’s monthly rate of return. The m-subscript in our sample assumes values for all months since January, 1946 for which data are available.

The residual from the OLS regression represented in equation (3) measures the extent to which the realized return differs from the expected return conditional upon the estimated regression parameters (b1j, b2j) and the market index [Lm − 1]. Thus, since the market has been found to adjust quickly and efficiently to new information, the residual must represent the impact of new information, about firm j alone, on the return from holding common stock in firm j.

Some Econometric Issues

One assumption of the OLS income regression model12 is that Mj and uj are uncorrelated. Correlation between them can take at least two forms, namely the inclusion of firm j in the market index of income (Mj), and the presence of industry effects. The first has been eliminated by construction (denoted by the j–subscript on M), but no adjustment has been made for the presence of industry effects. It has been estimated that industry effects probably account for only about 10 per cent of the variability in the level...