eBook - ePub

Risk and Acceptability

Mary Douglas

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Risk and Acceptability

Mary Douglas

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

First published in 1985, Mary Douglas intended Risk and Acceptability as a review of the existing literature on the state of risk theory. Unsatisfied with the current studies of risk, which she found to be flawed by individualistic and psychologistic biases, she instead uses the book to argue risk analysis from an anthropological perspective. Douglas raises questions about rational choice, the provision of public good and the autonomy of the individual.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Risk and Acceptability est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Risk and Acceptability par Mary Douglas en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Ciencias sociales et Antropología. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Chapter 1 Moral Issues in Risk Acceptability

Summary: This chapter indicates the risk issues that involve social justice and considers the neglect of that part of the topic of risk acceptability.

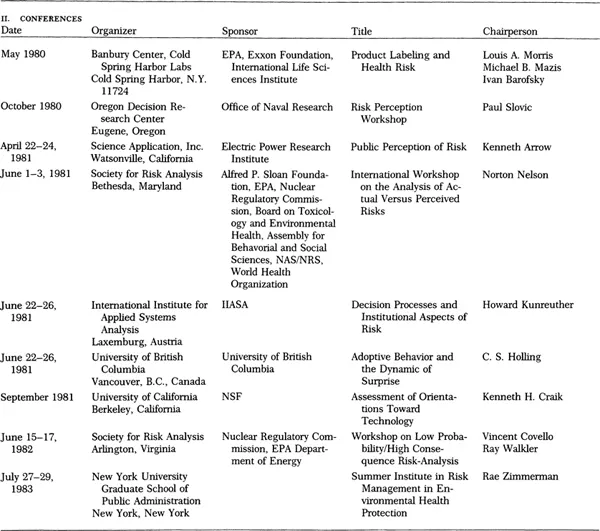

In every generation one or another branch of the social sciences is put on the witness stand to be interrogated about drastic problems—famine or economic recession, the causes of war or crime. For the last decade and more, such urgent questions have been about the risks of new technology. The fears and conscience of Western industrial nations have been roused by nuclear radiation, chemical wastes, asbestos and lead poisoning. In response, an important new subdiscipline of the social sciences has emerged which specifically addresses questions asked by industry and government about the public perception of risk. (See Table 1 on page 7.)

Table 1 Growth of Research in Risk Perception

I. RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS | ||

Date | Institution | Chairperson |

1969 | NSF Technology Assessment and Risk Analysis Group, 1800 G Street N.W. | Joshua Menkes |

Washington, DC 20550 | ||

Early 1970s | International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis Risk Group | Howard Kunreuther |

2361 Laxemburg, Austria | ||

1976 | Decision Research | Robert Kates |

1201 Oak Street | Roger Kasperson | |

Eugene, OR 97401 | ||

1978–79 | Institute for Risk Analysis | William Rowe |

American University | ||

Washington, DC 20016 | ||

1979 | National Research Council | |

2101 Constitution Avenue N.W. | ||

Washington, DC 20418 | ||

1979 | Center for Philosophy and Public Policy | Douglas MacLean |

University of Maryland | ||

College Park, Maryland 20742 | ||

1980 | Hudson Institute | Max Singer |

1500 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 810 | ||

Arlington, VA 22209 | ||

1980 | Society for Risk Analysis | Robert B. Cumming |

Oak Ridge National Laboratory | ||

Oak Ridge, TN 37830 | ||

1981 | Institute of Resource Ecology | C. S. Holling |

University of British Columbia | ||

Vancouver, B.C., Canada | ||

Technology Assessment Section | Harry Otway | |

System Analysis Division | ||

Joint Research Center | ||

Commission of the European Communities | ||

1–21020 Ispra (Varese), Italy | ||

Center for Technology and Policy Studies | P. J. M. Stallen | |

P.O. Box 541, 7300 AM | ||

Apeldoorn, Holland | ||

The public reception of any policy for risks will depend on standardized public ideas about justice. It is often held that perception of risk is directed by issues of fairness. The more that institutions depend upon personal commitment rather than upon coercion, the more explicitly they are monitored for fairness. The threshold of risk acceptability in the workplace is lowered when the workers consider themselves exploited. Awareness of medical risks is heightened if the medical profession is suspected of malpractice. Whether the sharper sensitivity to risks causes individuals to be more prudent in avoiding them is another matter.

Rawl’s concept of justice as fairness (1971), which lies at the basis of his moral philosophy, allows for cultural and social variation in concepts of fairness. But these variations would influence perception of risk. Furthermore, the variation in values corresponds to variation in possible kinds of organization. Selsnick (1969) found that fairness means one thing to unskilled manual workers (fairness as equal treatment for all) and another to clerical, professional, and management cadres (fairness as fair recognition of individual ability). Fairness as equality would seem appropriate in a highly ascriptive system with no opportunities for personal advancement and some expectations from collective bargaining; fairness as rewards for merit would be appealing to persons faced with opportunities for promotion. This is important if the claim is true that “the best predictor of opposition to nuclear energy is the belief that American society is unjust” (Rothman and Lichter 1982).

In some professional analyses the existing allocation of risks is taken to imply an accepted norm of distributive justice sustaining the moral fabric of society. Those who are in the more favored sectors of the community as regards the incidence of morbidity and mortality rates may be tempted not to think too deeply about its inequities. However, others would judge a society inequitable that regularly exposes a large percentage of its population to much higher risks than the fortunate top 10 percent.

The Poor Risk More

A cursory look at the labor and health statistics for the United States shows that, below a certain level, income is a good predictor of relative exposure to risks of most kinds. The percentage of persons who are unable through chronic ill health to carry on their major activity declines as income rises. In 1976–77 income had a greater impact than race upon a person’s Limitation of activity, but the death rates for disadvantaged minorities in 1977 were higher than for whites at all age levels until age 80 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1980a:2). Blue-collar workers reported a rate of 40.6 persons injured per 100 currently employed. An average of 21 percent of blue-collar workers were injured at work, and 19.89 percent of farm workers, compared with 5.1 percent of white-collar workers. At incomes less than $10,000, the picture worsens (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1980b).

Effects are cumulative. Excessive exposure to lead poisoning is particularly a danger for young children in poor families (largely due to household paint applied before the 1940s and to automobile emissions and made worse by iron deficiency and undernutrition) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1983). Likewise the effects of tobacco smoking will be greatly exacerbated for persons whose occupations expose their lungs to irritants, which means persons who work among factory fumes and dust.

Since the present distribution of risks reflects only the present distribution of power and status, fundamental political questions are raised by the justice issue. It is well said that the technical problems of risk analysis “pale before the political difficulties raised by the basic assumption that current risk–benefit tradeoffs are satisfactory” (Fischhoff et al. 1980:137). When a greater damage to a larger population can be avoided by relocating a dangerous industry to a sparsely settled area, fundamental ethical issues are raised. It is true that in a desert with a thin scattering of Indian tribes, fewer people will suffer damage. But why ever should the Indians of the American Southwest, already burdened by economic and health disadvantages, agree to be sacrificed to the greatest happiness principle? Should the price of a life be uniform for all lives? Should compensation be related to earning power? Should a young person’s life be counted more than an old person’s because its expected span of earning has been cut off short? The earning power principle comes into flagrant contradiction with equality. Intuitively, giving more risks to those who carry more smacks of elementary injustice. The employer’s liability toward his work force includes responsibility to prevent accidents, to provide full information about occupational risks, and to ensure appropriate compensation for victims. How should his liabilities be traded off against his costs? Should it be left to his conscience? Should the decisions be regulated from above? The answers are about political, economic, and moral pressures that influence the public feeling of what is tolerable.

The question of acceptability of risk involves freedom as well as justice. Consider the workers’ choice: If they are offered danger money for risky work, are they to be the sole judges of what risks they should take or should they be regulated? The freedom of the individual in liberal democracy is at issue. And when it comes to danger money, it is not clear that the riskier jobs really are the most highly compensated (Graham and Shakow 1981). The basis of compensation rates is generally related to normal expectation of rewards, but what about expectations of injury? It seems that in the United States nonwhites have higher expectations of being injured at work than whites. Figures based on medical attendance show a lower rate of reported injury for nonwhites but a greater proportion of physical damage. This means that they do not trouble to turn up at the clinic for minor injuries but use it if severely incapacitated (U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare 1979). If a community which once heroically accepted the dangers of coal mining is now suffering the misery of unemployment, who is to tell them not to have a liquid natural gas site in their neighborhood, if they perceive it as a source of incomes and pensions? Or if a community, using its regularly instituted procedures of vote-casting, rejects or hesitates to accept a nuclear plant in its midst, what is the ethical status of an offer to buy off the opposition? What kind of community amenities can be provided that will compensate for the risks? In the time span of the bargains, will the promised benefits last longer than the risks? Has a community any inherent right to commit its future generations to heavy risks? The ethical theory on which disputants draw is in disarray.

Rights of Future Generations

Golding (1972) pours scorn on attempts to secure the ethical claims of Martians, Venusians, strange peoples on this earth, and unborn generations: “If someone finds it difficult to think of having an obligation to his unborn child, he should find it difficult to think of having an obligation towards the community of humans (humanoids?) fifty generations hence.” Schwartz argues that long-range welfare policies to give benefit to future generations cannot be justified by appeal to welfare of remote unidentifiable individuals: Ethically objectionable acts must have victims (Schwartz 1979. The counterargument is made by Routley (1979) on behalf of future people. (See also Barry and Sikora 1978.)

A wider failure to think systematically about distributive justice is inherent in the most prestigious part of the conceptual apparatus of Western social thought. A sigh of relief seems to have been heard from economists when they realized that a fully subjectivized utility theory gave them an analytic tool that could not deal with absolutes or objective rights and wrongs. Dealing only with individuals’ ranked preferences, the economists’ subject matter was withdrawn from the political arena. The tool of comparison seemed to achieve the value-neutrality of an exact science. It took some time to accept the cost of not being able to say anything about distributive justice, but when Lionel Robbins had announced this clearly the whole topic is said to have been quietly dropped. “The attack of Robbins (1932) and others on interpersonal comparability does not distinguish between some comparability and total comparability of units, and the consequence has been the virtual elimination of distributional questions from the formal literature on welfare economics …” (Sen 1970:99–100). Without an intellectually respectable way of discussing justice, there is no way of discussing the acceptability of risk, as most policy issues concerning risk raise grave problems of justice.

Writers on risk acceptability tend to content themselves with a perfunctory tribute to moral issues or with inventories of ethical problems.

Salute to Moral Principles

Fischhoff et al. (1980) are emphatic that values affect acceptability: the “search for an ‘objective method’ for solving problems of acceptable risk is doomed to failure and may blind the searchers to the value-laden assumptions they are making … not only does each approach fail to give a definitive answer, but it is predisposed to representing particular interests and recommending particular solutions. Hence, choice of a method is a political decision with a distinct message about who should rule and what should matter. … The controlling factor in many acceptable-risk decisions is how the problem is defined. “They recommend making explicit the limitations of methods of analysis, facilitating consideration of risk problems within existing democr...