![]()

Part One

The Development of Macrodynamics

The advisability of beginning the study of any field of economic analysis along historical lines is debatable. Certainly such a circuitous course is not justified if past studies are considered only as error-ridden accounts, which merely anticipate contemporary analysis. Yet, to see in the evolution of economic thought only a perpetual recommencement of the same debates and a perpetual reproduction of the same divisions suggests an excessively pessimistic view of the scientific status of economic analysis. Like any other discipline, economic science has progressed through alternating constructive development with discontinuous reorganisation of its visions of reality around new paradigms. Thus, current models may be studied as much from the contemporary (synchronistic) point of view of their structures as from the historical (diachronistic) perspective of their origins.

We will study the development of macrodynamics up to the so-called Keynesian Revolution. Three stages in this development can be distinguished. With the ‘great dynamics’ (W. J. Baumol, Economic Dynamics, Macmillan, 1959), there appeared the aggregative systems of interpretation of economic movement of Ricardo and Marx. The pre-Keynesian period witnessed a burgeoning cluster of works devoted to the study of growth and business cycles from a disequilibrium perspective. And lastly, it was through the Keynesian Revolution and the dual process of neoclassical synthesis and counter-revolution which followed it, that macrodynamic analysis reached what appeared, ten years ago, to be its definitive form.

![]()

1 Great Dynamic Theories of the Past

The earliest representations of the complete network of economic activity were constructed by Boisguilbert and later by the physiocrats, in terms of the circulation of wealth. Without ignoring the genuine dynamic aspects of their work, relating in the former case to the nature of crises, in the latter to the accumulation of capital, we will instead restrict ourselves to a presentation of the grand systems of interpretation of economic movement advanced by the English Classical economists, in particular Ricardo, and by Marx. Clearly, this account does not aim to give a complete historical picture of the work of these authors, such as might be found in a more specialised work.1

1 The Ricardian Dynamic Mechanism

David Ricardo, who wrote at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, was the principal representative of the English Classical school founded forty years previously with the publication of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. This book laid down quite clearly the two components which, these writers believed, constituted economic movement: growth, led by capital accumulation and culminating in a steady state, and short-term fluctuations which market mechanisms themselves would resolve, to the extent that they were allowed into play.

A The Growth Process and the Constraints on Growth

The English Classical economists witnessed the ‘take-off’ of the British economy in the first industrial revolution. They identified the accumulation of capital as the engine of growth, a process which seemed to them to have a limited life-time and to be destined to culminate in a stationary state.

In Smith’s view it was the division of labour2 which permitted the accumulation of wealth, but the division of labour also implied that in contrast to the traditional artisan, the industrial labourer could no longer live from the sale of his own produce. His wage had to be advanced to him from a subsistence fund, which along with the instruments and materials he required, constituted the capital stock.

Profit was at once both the source and the objective of the accumulation of capital – hence the emphasis placed on the distribution of income in Ricardo’s analysis. ‘It is as impossible for the farmer or manufacturer to live without profits, as it is for the worker to exist without a wage. The motivation to accumulate will diminish with every reduction in profits.’3

It is not possible to introduce Ricardian dynamic theory without first briefly outlining Ricardo’s position on the question of value. Beginning from an initial reaffirmation of the labour theory of value, in its strict form, he first assumes that the exchange value or natural price of reproducible goods is determined by the quantity of direct and indirect labour required for their production. But he then points out that a significant role is also played by the distribution of costs between wages and profits, which is linked to the mean gestation period of capital in the production process under consideration. Therefore, Ricardo only adopts labour-value as an approximation.

But, conscious of the unsatisfactory nature of this solution, Ricardo searched all his life for an invariant standard of value, which would not itself be affected by changes in the distribution of income, and so could provide an absolute reference point from which to measure the value of other goods.4

For want of a solution to this problem, Ricardo assumed in the first presentation of his analysis that there was only one basic commodity (that is to say, only one commodity used in the production of all others) which was at the same time the product of the agricultural sector and the sole means of subsistence of labour: corn. This good was thus employed as the unit of measurement for every variable. Income was distributed between landowners who received rent, wage workers and capitalists – that is, farmers and manufacturers who collected profits. The latter were considered a surplus, rents and wages being determined ‘up-stream’. Ricardo believed that the ‘natural wage’ which prevailed in the medium to long term, would stabilise at the subsistence level, determined by custom as well as by physiological considerations. The strategic component was the movement of property rent.

Property rent was said to result from the difference in fertility of different types of soil, and thus had a differential character. Like all classical writers, Ricardo accepted that decreasing returns prevailed in agriculture and constant returns prevailed in industry. So, strictly speaking the labour theory of value could not be applied to corn, because it implied constant returns. Ricardo applied it at the margin,assuming that the natural price of corn was the labour cost of the most costly output, obtained on the least fertile land. Thus, on all other lands, there was a divergence between the price of corn and its cost in terms of wages and profits, and this was rent.

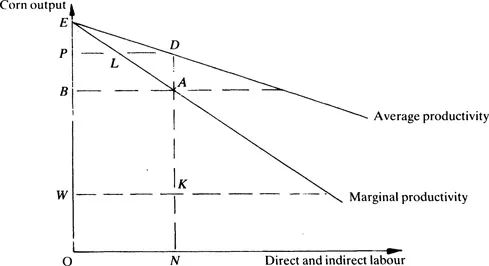

Now, in this model when output rises, less fertile lands are brought into cultivation and the labour-cost of corn rises. Hence, total output in terms of corn increases less than employment. Furthermore, an increasing proportion of total output is seized by rent. Kaldor’s classic diagram5 illustrates the dynamics of the determination of rent and distribution.

The respective axes represent direct and indirect labour (labour and capital in modern terminology), which are assumed to vary together (in fixed proportions), and output in the agricultural sector, assumed to be made up solely of corn. As a result of diminishing returns, the average productivity of labour (direct and indirect) decreases, so marginal productivity must be less than the average. The total level of output from a level of employment N is found either by multiplying ON by average productivity (giving the area of ONDP) or by integrating the marginal productivity function between O and N (giving the area of OEAN), which implies that the triangles EPL and LDA are congruent (given that the average marginal productivity schedules are assumed to be linear).

The remuneration, in wages and profits, for one unit of direct or indirect ‘labour’ in standard terms is just equal to its marginal productivity at N, that is the distance NA. If it were not, marginal land would not be exploited or it would not be truly marginal. The total cost of corn production in wages and profits measured in corn is thus determined by the area of the rectangle OBAN. So, by subtraction property rent is found to be equal to the area EBA. It is well worth noting that rent is here determined by the difference between the productivity of marginal land and that of the most fertile land, or in other words, by the slope of the marginal productivity function – that is, by purely technical factors.

How the cost of production OBAN is divided between wages and profits is quite simply determined. The fact that the real wage rate, in terms of corn, is predetermined implies a total value of wages equal to the area OWKN. Profits are simply a residual over and above this – WBAK. As wages are advanced over an average period assumed to be one year, the annual wage flow is also equal to the society’s wage fund. In the absence of fixed capital, the rate of profit is thus equal to the ratio of the areas WBAK/OWKN.

We may complete the dynamics of the model by noting the dual causality of the wage fund equation W = wN.

In the short term this equation determines the wage rate. Capital accumulation entails an increase in the market wage rate, which, on account of the Malthusian population principle, will lead to a population expansion which will bring the wage back to its natural, subsistence level. In the long term, the wage fund equation operates as a demand function for productive labour N = W/w. Accumulation of capital will then result in increased employment of direct and indirect labour. The margin between the average and marginal productivity of labour will grow, so rent will signify a proportionately increasing levy. With a constant real wage rate and falling marginal labour productivity, it is clear that the share of profits can only contract.

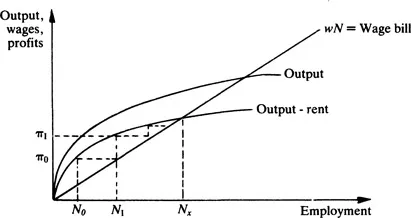

Another standard diagram, presented by Baumol,6 illustrates this evolutionary process. Total output is now measured on the y-axis. This output grows at a decreasing rate but consistently faster than the total cost of production (output minus rent or alternatively wages plus profits). Wages, expressed in corn, are proportional to employment and equal to wN. Hence, we obtain the graph in Figure 1.2.

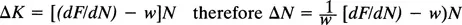

If F(N) is the total output of corn, N dF/dN is the total cost of production ((ON × NA) on Kaldor’s graph), so rent comes to N(F/N − dF/dN) and profit to (dF/dN − w) N. We assume that profit is entirely reinvested in the form of the wage fund.

and...