![]()

1

Lord of the Worlds

‘it is time we realized there is only “one world” even in history. If there is to be an “Islamic world,” this can be only in the future’

– Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam1

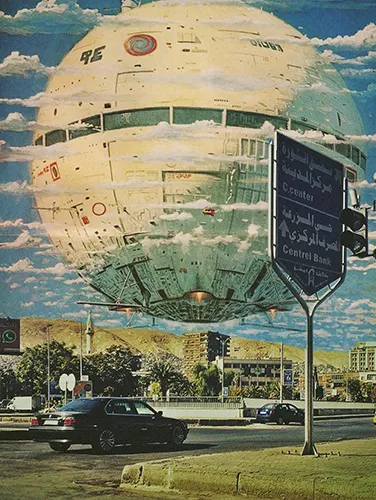

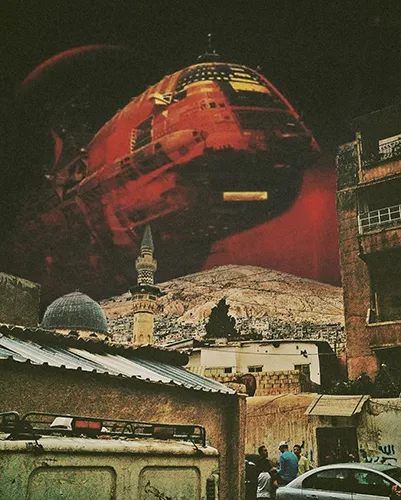

During the war that had begun in 2011, various forces fought over Syria. In the surrealist art of Ayham Jabr, one of them was Martian. Unlike the woman whom he loved, Jabr did not flee his country as a refugee. Instead, the young graphic designer stayed in Damascus. With little more than a laptop, an internet connection and a pirated copy of Adobe Photoshop, he created digital collages and distributed them via social media. One of his series made in 2016 was entitled Damascus under Siege (Figures 1 and 2). Combining scanned photographs and images found on the web, the collages show Martian spaceships hovering over his home city. ‘They say they came for peace’, Jabr commented. ‘But who is really coming for peace? What they really brought is total annihilation.’ The artist remained defiant. Those who were trying to destroy Syria would not succeed. ‘After all the wars’ in the past, his country had ‘stood up again’.2

With his surrealism, Ayham Jabr was unusual among the artists who lived through the Syrian Civil War. Although he continued to work in the capital, he did not produce simple propaganda for the government. President Bashar al-Assad and his family hardly appeared. Nor was Jabr among the many artists who engaged in acts of creative resistance against the regime.3 His work was mainly critical of foreign interventions. ‘The terror the West is sending us is worse than hell itself’, complained Jabr. His response was largely pacifist. The actual attacks on Damascus, and the ones of his imagination, were ‘about greed, the illusion of power and striving for eternal reputation’. In the end, the violence did not produce any winners. ‘Everyone has lost relatives’, Jabr lamented. ‘That is what is so hideous about the war: destruction and sorrow will cover all of us.’4

Figure 1 Damascus under Siege-7 (2016). Courtesy of Ayham Jabr.

Figure 2 Damascus under Siege-3 (2016). Courtesy of Ayham Jabr.

While Ayham Jabr was unusual among visual artists, he was not the only creator of science fiction in wartime Syria. Various amateurs created videos and memes inspired by Japanese anime series like UFO Robot Grendizer with their simple plots of good versus evil. Even if they were critical of the government, social media activists thus reused Arabic-dubbed material that had been broadcast by state television stations since the 1980s.5 The Ministry of Culture itself also published an entire magazine entitled Science Fiction. The editor-in-chief was the scientist, broadcaster and writer Taleb Omran. He was supported by an advisory board consisting of authors from Egypt, France, Kuwait, Lebanon and Morocco. The periodical included stories, reviews and literary studies. Other parts of the magazine were dedicated to science, both mainstream and fringe. An issue from 2013, for instance, featured articles on black holes, pollution and ‘visitors from space in historical documents’.6 The Arabic text of the various issues was interspersed with colourful images from popular global productions, such as StarCraft, Star Trek and Star Wars. Probably reproduced without permission, these images added appeal to the stories in a cost-effective way.

Science Fiction was one of the outcomes of the Lucian the Syrian Symposium, which had been held with sponsorship by the Ministry of Culture in Damascus in 2007. It was named after Lucian of Samosata, who wrote A True Story about a trip to the Moon in the second century. After discussing the history and philosophy of science fiction, the participants passed several recommendations. Besides the establishment of the magazine, they asked for support for the translation of literature into and from Arabic. Another suggestion was the teaching of their genre in secondary schools and at universities. The top recommendation, however, was the creation of an Association of Arab Science Fiction Writers, which was realized two years later.7

Although sponsored by a national institution, the Lucian the Syrian Symposium had an impact beyond the country’s borders. Prominent authors, including Nehad Sherif from Egypt and Taibah Al-Ibrahim from Kuwait, were among the speakers. ‘Overall the event was impressive’, reported Kawthar Ayed, then a graduate student in Aix-en-Provence and Sousse. ‘I have in the past attended SF events in Tunisia, France, Spain and so forth, but nowhere with such a reception, nor such broadmindedness.’ Riad Agha, the minister of culture gave the opening speech, defending science fiction as a worthy genre and acknowledging his personal interest. Newspapers covered the symposium, and talks were recorded for a weekly television programme presented by Taleb Omran.8

The state’s support for science fiction was remarkable for surviving long into the Syrian Civil War. By the time of its outbreak in March 2011, thirty-three issues of Science Fiction had appeared. Subsequently, the magazine’s frequency was reduced from monthly to quarterly. Still, by January 2019, sixty-eight issues plus accompanying books had been produced. In addition, Omran established a new monthly called Scientific Literature in 2013. This periodical was issued by Damascus University and used a similar style and layout. Authors from elsewhere in the Arab world continued to advise the Syrian editor-in-chief. Amid shortages of all kinds, sixty-three issues of the magazine had appeared by November 2018. In the meantime, Omran had founded yet another literary journal called Circles of Creativity, which included Arabic science fiction as well. The Syrian Arab News Agency regularly publicized new issues of all three periodicals alongside updates from the front line.

Islam and science fiction

Taleb Omran had thus convinced his government to invest scarce resources in a highly speculative endeavour. ‘Why science fiction?’ asked Riad Agha in his opening article of the first issue of Science Fiction. This form of literature was the ‘legitimate son of the age of science in which we live’. Science fiction was also ‘a smart education tool that gives children a more comprehensive view and understanding of science, its achievements and its offerings’. Agha then quoted the American writer Isaac Asimov, whose name he Arabized as ‘Isḥāq ʿAẓīmūf’. Out of 100 children reading science fiction, at least one would later become a scientist, Asimov had predicted.9 In a subsequent opening article to the second issue of Science Fiction, Agha again stressed the importance of the genre. This form of fiction is ‘the literature of the future’.10

In emphasizing the educational value of the genre, Riad Agha meant its fictional as much as its scientific aspects. ‘Man is an imaginative being’, the official stressed. ‘The more he excels in imagining, the more he excels in innovation and invention.’ ‘Imagination is the evocation of images’ before they are fully understood. Children create images, in which they ‘drive a spacecraft’ or ‘meet intelligent beings from other planets’.11 Agha further mentioned dreams of defeating old age and sickness, landing on ‘distant planets’ and meeting with ‘the beings of other worlds’. Such creatures could be portrayed as ‘aggressive’ and ‘authoritarian’, striving for control and influence. Alternatively, they may be ‘peaceful’ and ‘seeking friendship, love, and cooperation’.12

Many observers of Arab politics would have been surprised by the minister’s commitment to nurturing the imagination. In 2009, the British journalist Brian Whitaker published a book titled What’s Really Wrong with the Middle East. He wrote, ‘Education in the Arab countries is where the paternalism of the traditional family structure, the authoritarianism of the state and the dogmatism of religion all meet, discouraging critical thought and analysis, stifling creativity and instilling submissiveness.’13 Whitaker based his criticism on the United Nations’ Arab Human Development Report 2003. This document had claimed that ‘curricula taught in Arab countries seem to encourage submission, obedience, subordination and compliance, rather than free critical thinking’.14 It is puzzling then that an authoritarian regime would support science fiction as a very liberated genre, especially as it was struggling to control its population.

Did the Syrian state sponsor science fiction as a kind of ‘commissioned’ or ‘licensed criticism’?15 In other words, did speculative art serve as a safety valve for grievances or at least as a breathing space amid repression? The titles of some of Omran’s novels, such as The Search for Other Worlds, might suggest escapism.16 The magazine Science Fiction also offered some criticism of Arab politics, while avoiding mentions of the Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. The first issue included an article by the Syrian writer Zuhair Ghanem under the title ‘The Fiction of Arabic Science Fiction Literature’. ‘We have science fiction writers, but don’t say that we have a science fiction literature’, he cautioned. This genre in the Arab world was still in its infancy, he claimed, ‘because of the dire conditions, backwardness, illiteracy, and the absence of mental structures and scientific research’. He further ex...