![]()

Chapter 1

Historical Context

Human-computer interaction. In the beginning, there were humans. In the 1940s came computers. Then in the 1980s came interaction. Wait! What happened between 1940 and 1980? Were humans not interacting with computers then? Well, yes, but not just any human. Computers in those days were too precious, too complicated, to allow the average human to mess with them. Computers were carefully guarded. They lived a secluded life in large air-conditioned rooms with raised floors and locked doors in corporate or university research labs or government facilities. The rooms often had glass walls to show off the unique status of the behemoths within.

If you were of that breed of human who was permitted access, you were probably an engineer or a scientist—specifically, a computer scientist. And you knew what to do. Whether it was connecting relays with patch cords on an ENIAC (1940s), changing a magnetic memory drum on a UNIVAC (1950s), adjusting the JCL stack on a System/360 (1960s), or greping and awking around the unix command set on a PDP-11 (1970s), you were on home turf. Unix commands like grep, for global regular expression print, were obvious enough. Why consult the manual? You probably wrote it! As for unix’s vi editor, if some poor soul was stupid enough to start typing text while in command mode, well, he got what he deserved.1 Who gave him a login account, anyway? And what’s all this talk about make the state of the system visible to the user? What user? Sounds a bit like … well … socialism!

Interaction was not on the minds of the engineers and scientists who designed, built, configured, and programmed the early computers. But by the 1980s interaction was an issue. The new computers were not only powerful, they were useable—by anyone! With usability added, computers moved from their earlier secure confines onto people’s desks in workplaces and, more important, into people’s homes. One reason human–computer interaction (HCI) is so exciting is that the field’s emergence and progress are aligned with, and in good measure responsible for, this dramatic shift in computing practices.

This book is about research in human-computer interaction. As in all fields, research in HCI is the force underlying advances that migrate into products and processes that people use, whether for work or pleasure. While HCI itself is broad and includes a substantial applied component—most notably in design—the focus in this book is narrow. The focus is on research—the what, the why, and the how—with a few stories to tell along the way.

Many people associate research in HCI with developing a new or improved interaction or interface and testing it in a user study. The term “user study” sometimes refers to an informal evaluation of a user interface. But this book takes a more formal approach, where a user study is “an experiment with human participants.” HCI experiment are discussed throughout the book. The word empirical is added to this book’s title to give weight to the value of experimental research. The research espoused here is empirical because it is based on observation and experience and is carried out and reported on in a manner that allows results to be verified or refuted through the efforts of other researchers. In this way, each item of HCI research joins a large body of work that, taken as a whole, defines the field and sets the context for applying HCI knowledge in real products or processes.

1.1 Introduction

Although HCI emerged in the 1980s, it owes a lot to older disciplines. The most central of these is the field of human factors, or ergonomics. Indeed, the name of the preeminent annual conference in HCI—the Association for Computing Machinery Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (ACM SIGCHI)—uses that term. SIGCHI is the special interest group on computer-human interaction sponsored by the ACM.2

Human factors is both a science and a field of engineering. It is concerned with human capabilities, limitations, and performance, and with the design of systems that are efficient, safe, comfortable, and even enjoyable for the humans who use them. It is also an art in the sense of respecting and promoting creative ways for practitioners to apply their skills in designing systems. One need only change systems in that statement to computer systems to make the leap from human factors to HCI. HCI, then, is human factors, but narrowly focused on human interaction with computing technology of some sort.

That said, HCI itself does not feel “narrowly focused.” On the contrary, HCI is tremendously broad in scope. It draws upon interests and expertise in disciplines such as psychology (particularly cognitive psychology and experimental psychology), sociology, anthropology, cognitive science, computer science, and linguistics.

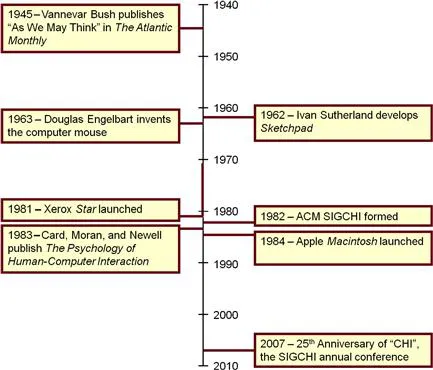

Figure 1.1 presents a timeline of a few notable events leading to the birth and emergence of HCI as a field of study, beginning in the 1940s.

Figure 1.1 Timeline of notable events in the history of human–computer interaction HCI.

1.2 Vannevar Bush’s “as we may think” (1945)

Vannevar Bush’s prophetic essay “As We May Think,” published in the Atlantic Monthly in July, 1945 (Bush, 1945), is required reading in many HCI courses even today. The article has garnered 4,000+ citations in scholarly publications.3 Attesting to the importance of Bush’s vision to HCI is the 1996 reprint of the entire essay in the ACM’s interactions magazine, complete with annotations, sketches, and biographical notes.

Bush (see Figure 1.2) was the U.S. government’s Director of the Office of Scientific Research and a scientific advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. During World War II, he was charged with leading some 6,000 American scientists in the application of science to warfare. But Bush was keenly aware of the possibilities that lay ahead in peacetime in applying science to more lofty and humane pursuits. His essay concerned the dissemination, storage, and access to scholarly knowledge. Bush wrote:

the summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships (p. 37).4

Figure 1.2 Vannevar Bush at work (circa 1940–1944).

Aside from the reference to antiquated square-rigged ships, what Bush says we can fully relate to today, especially his mention of the expanding human experience in relation to HCI. For most people, nothing short of Olympian talent is needed to keep abreast of the latest advances in the information age. Bush’s consequent maze is today’s information overload or lost in hyperspace. Bush’s momentarily important item sounds a bit like a blog posting or a tweet. Although blogs and tweets didn’t exist in 1945, Bush clearly anticipated them.

Bush proposed navigating the knowledge maze with a device he called memex. Among the features of memex is associative indexing, whereby points of interest can be connected and joined so that selecting one item immediately and automatically selects another: “When the user is building a trail, he names it, inserts the name in his code book, and taps it out on his keyboard” (Bush, 1945, p. 44). This sounds like a description of hyperlinks and bookmarks. Although today it is easy to equate memex with hypertext and the World Wide Web, Bush’s inspiration for this idea came from the contemporary telephone exchange, which he described as a “spider web of metal, sealed in a thin glass container” (viz. vacuum tubes) (p. 38). The maze of connections in a telephone exchange gave rise to Bush’s more general theme of a spider web of connections for the information in one’s mind, linking one’s experiences.

It is not surprising that some of Bush’s ideas, for instance, dry photography, today seem naïve. Yet the ideas are naïve only when juxtaposed with Bush’s brilliant foretelling of a world we are still struggling with and are still fine-tuning and perfecting.

1.3 Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad (1962)

Ivan Sutherland developed Sketchpad in the early 1960s as part of his PhD research in electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.). Sketchpad was a graphics system that supported the manipulation of geometric shapes and lines (objects) on a display using a light pen. To appreciate the inferior usability in the computers available to Sutherland at the time of his studies, consider these introductory comments in a paper he published in 1963:

Heretofore, most interaction between man and computers has been slowed by the need to reduce all communication to written statements that can be typed. In the past we have been writing letters to, rather than conferring with, our computers (Sutherland, 1963, 329).

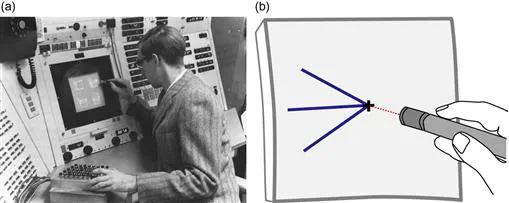

With Sketchpad, commands were not typed. Users did not “write letters to” the computer. Instead, objects were drawn, resized, grabbed and moved, extended, deleted—directly, using the light pen (see Figure 1.3). Object manipulations worked with constraints to maintain the geometric relationships and properties of objects.

Figure 1.3 (a) Demo of Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad. (b) A light pen dragging (“rubber banding”) lines, subject to constraints.

The use of a pointing device for input makes Sketchpad the first direct manipulation interface—a sign of things to come. The term “direct manipulation” was coined many years later by Ben Shneiderman at the University of Maryland to provide a psychological context for a suite of related features that naturally came together in this new genre of human–computer interface (Shneiderman, 1983). These features included visibility of objects, incremental action, rapid feedback, reversibility, exploration, syntactic correctness of all actions, and replacing language with action. While Sutherland’s Sketchpad was one of the earliest examples of a direct manipulation system, others soon followed, most notably the Dynabook concept system by Alan Kay of the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) (Kay and Goldberg, 1977). I will say more about Xerox PARC throughout this chapter.

Sutherland’s work was presented at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) conference in Detroit in 1963 and subsequently published in its proceedings (Sutherland, 1963). The article is available in the ACM Digital Library (http://portal.acm.org). Demo videos of Sketchpad are available on YouTube (www.youtube.com). Not surprisingly, a user study of Sketchpad was not conducted, since Sutherland was a student of electrical engineering. Had his work taken place in the field of industrial engineering (where human factors is studied), user testing would have been more likely.

1.4 Invention of the mouse (1963)

If there is one device that symbolizes the emergence of HCI, it is the computer mouse. Invented by Douglas En...