![]()

Part I

Biochemical Changes in Raw Foods

Chapter 1 Cereals and Legumes

Chapter 2 Fruits and Vegetables

Chapter 3 Meat and Fish

Chapter 4 Milk

Chapter 5 Egg Components in Food Systems

![]()

Chapter 1

Cereals and Legumes

Kequan Zhou∗, Margaret Slavin†, Herman Lutterodt∗∗, Monica Whent∗∗, N.A. Michael Eskin‡ and Liangli Yu∗∗

∗Department of Nutrition and Food Science, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA

†Department of Nutrition and Food Studies, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia, USA

∗∗Department of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA

‡Department of Human Nutritional Science, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Chapter Outline

Part I: Cereals

I. Introduction

II. Cereal Grain Structure

III. Cereal Grain Composition

A. Amyloplasts

B. The Starch Granule

C. Biosynthesis of Starch

D. Sucrose Starch Conversion in Developing Grains

E. Starch Synthesis

F. Starch Synthesis: Amylopectin

G. Protein Bodies

H. Origin of Protein Bodies

I. Classification of Plant Proteins

J. Prolamins

K. Protein Synthesis

L. Lipids

IV. Germination of Cereals

A. Mobilization of Cereal Starches by α-Amylase

B. Biosynthesis of α-Amylase during Germination

C. α-Amylase Activity in Germinated Cereals

D. Effect of Germination on Flour Quality

E. Treatment of Sprouted Grain: Reduction of α-Amylase

F. Mobilization of Proteins during Germination

G. Lipid Mobilization during Germination

V. Storage of Grains

A. Respiration

1. Effect of Moisture Content

2. Effect of Temperature

B. Prolonged Storage of Grains and Flour

Part II: Legumes

I. Introduction

II. Legume Seed Structure

III. Legume Seed Composition

A. Proximate Composition

B. Protein

1. Nitrogen Fixation

2. Classification

3. Protein Structure and Properties

4. Protein Quality

C. Carbohydrates

1. Overview

2. Insoluble Carbohydrate

3. Soluble Carbohydrate

4. Conclusion

D. Lipids

E. Other Components of Interest

1. Enzyme Inhibitors

2. Lectins

3. Lipoxygenase

IV. Effects of Germination

A. Carbohydrates

B. Lipids

C. Proteins

D. Vitamins and Minerals

E. Anti-nutritional Factors

1. Trypsin Inhibitor Activity

2. Phytic Acid

F. Nutraceutical Components

G. Aesthetic Food Quality

V. Effects of Fermentation

VI. Storage

A. Respiration, Moisture, and Temperature

B. Seed Aging and Food Quality

C. Effect on Isoflavones

References

Part I: Cereals

I Introduction

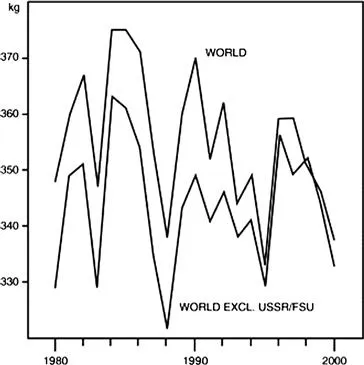

Cereals are members of the large monocotyledonous grass family, the Gramineae, which mainly consists of wheat, maize, barley, oats, rice, and sorghum (Anderson et al., 2000). Cereal-based foods have been a staple dietary source for the world’s population for centuries. Cereal grains contain the macronutrients (protein, fat, and carbohydrate) required by humans for growth and maintenance, contributing approximately 70% and 50% of the total calories and protein, respectively (Topping, 2007). Cereal grains also supply important minerals, vitamins, and other micronutrients essential for optimal health. They still provide 20% of magnesium and zinc, 30–40% of carbohydrate and iron, 20–30% of riboflavin and niacin, and over 40% of thiamine in the diet (Marston and Welsh, 1980). Global cereal production per capita fluctuated around 280 kg per year during the first half of the twentieth century, as seen in Figure 1.1 (Gilland, 2002). The world production of cereal is projected to be 3555 Mt, with per capita production of 378 kg (Gilland, 1998). Cereal-based food, especially whole grains, have shown the potential for health promotion, linking to reduced risk of several chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer (Truswell, 2002; Montonen et al., 2003; Slavin, 2000; Slavin et al., 1999). These beneficial effects are attributed to numerous phytochemicals contained in the grains. Therefore, this chapter will discuss those biochemical changes taking place during development, germination, and storage of cereal grains, with particular attention to wheat.

FIGURE 1.1 Cereal production per capita, 1980–2000.

(Sources: FAOSTAT; US Bureau of the Census; adapted from Gilland, 2002.)

II Cereal Grain Structure

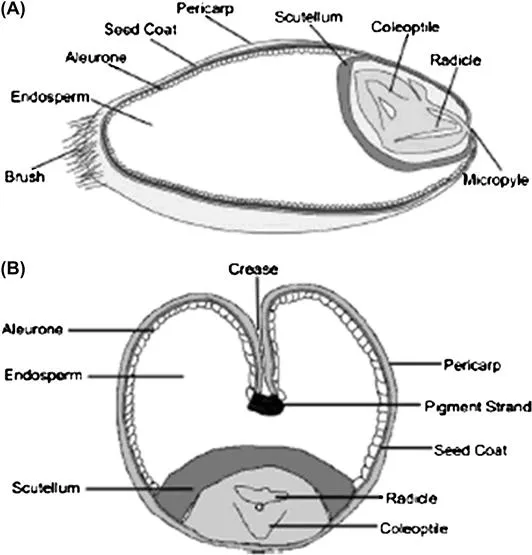

The different tissues constituting the cereal seed are generally described in terms of their embryogenic origin and structure (Evers et al., 1999). The cereal seed is composed of three main tissues: the embryo, the endosperm, and the aleurone layer surrounding the storage endosperm. This is illustrated for wheat in Figure 1.2, in which the endosperm comprises over 80% of the grain weight while the aleurone cells and the germ tissue containing the embryo embedded in the surrounding scutellum account for 15% and 3%, respectively. The peripheral tissues of the grain overlying the starchy endosperm are made up successively from the outer to the inner surface: the outer pericarp, the inner pericarp, seed coat, hyaline layer, and the aleurone layer (Barrona et al., 2007). The germ comprises the embryonic axis and the scutellum. The anatomical structure of all cereal grains is essentially similar with some minor differences. For instance, wheat and maize are surrounded by a fruit coat or pericarp and seed coat or testa, together referred to as a naked caryopsis. In the case of barley, oats, and rice, however, an additional husk is found surrounding the caryopsis or kernel of the grain.

FIGURE 1.2 Diagram of wheat grain showing major structures in (A) longitudinal and (B) transverse sections

(Rathjen et al., 2009 with permission).

III Cereal Grain Composition

Cereal grains are highly nutritious, and the major components of the grain are proteins (approximately 10–15%) and starch (approximately 60–70% of grain), with non-starch polysaccharides derived from the cell walls accounting for about 3–8% of the total (Saulniera et al., 2007). The composition of cereals varies and highly depends on grain variety, growing conditions, husbandry, and infection (Tester, 1995). The starchy endosperm constitutes the major portion of the cereal seed and provides the nutrients necessary for embryo development during germination. The nutrients are made available by the release of enzymes from the aleurone layer and embryo, which hydrolyze the endosperm reserves. These reserves are contained in discrete storage bodies identified as starch granules and protein bodies. These components have major effects on the use of cereal grain due to their physiochemical properties during milling and food processing. It is worth noting that the non-digestible carbohydrates in cereal grains have received increased attention as a significant source of dietary fiber, and are purported to have an impact on the nutritional quality and health-enhancing effects of cereal foods (Salmeron et al., 1997). In addition, polysaccharides in cereals are associated with many other substances, mostly with proteins, polyphenols, and phytate, which can modify mineral binding by dietary fiber (Vitali et al., 2008).

A Amyloplasts

Amyloplasts are plastids or organelles responsible for the storage of starch granules. The rate of starch synthesis in cereal grains is one of the factors affecting both grain size and yield (Kumar and Singh, 1980). In the mature endosperm of wheat, barley, and rye, starch is found as two distinct fractions based on the size of the granules. The primary or A-type starch granules range in size from 20 to 45 μm, while the secondary or B-type granules rarely exceed 10 μm in diameter (Evers, 1973). Examination of the particle size distribution in wheat endosperm starch by Evers and Lindley (1977) showed that those starch granules less than 10 μm in diameter accounted for approximately one-third of the total weight of starch. The presence of these two starch granule types in wheat kernels was confirmed in studies by Baruch et al. (1979). They found that the size of the starch was affected by seasonal changes in much the same way as grain yield and protein content. The starch granule occupies only a very small part of the total plastid during initial kernel development but accounts for close to 93% at maturity (Briarty et al., 1979). In the mature endosperm, A-type starch granules account for only 3% of the total number of granules although they represent ...