eBook - ePub

Philosophy in 40 Ideas

Lessons for life

Alain de Botton, Alain Botton

This is a test

Partager le livre

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Philosophy in 40 Ideas

Lessons for life

Alain de Botton, Alain Botton

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

A thought-provoking introduction to philosophy through 40 key ideas. This book artfully draws together forty of the greatest and most useful ideas found in philosophy, taking us on a journey around key concepts from both Eastern and Western cultures.Exploring relevant issues like work, love, anxiety, self-knowledge, and happiness, this essential guide reminds us of the wit, humanity, and relevance of great philosophers including Nietzsche, Heidegger, Confucius, Lao Tzu, and Buddha.

- PHILOSOPHY FOR EVERYDAY LIFE

- 40 KEY CONCEPTS presented in short, poetic chapters.

- ANCIENT WISDOM, CONTEMPORARY APPLICATION explains how philosophy is still applicable today.

- FULLY ILLUSTRATED THROUGHOUT

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Philosophy in 40 Ideas est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Philosophy in 40 Ideas par Alain de Botton, Alain Botton en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Philosophy et History & Theory of Philosophy. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

PhilosophySous-sujet

History & Theory of Philosophy

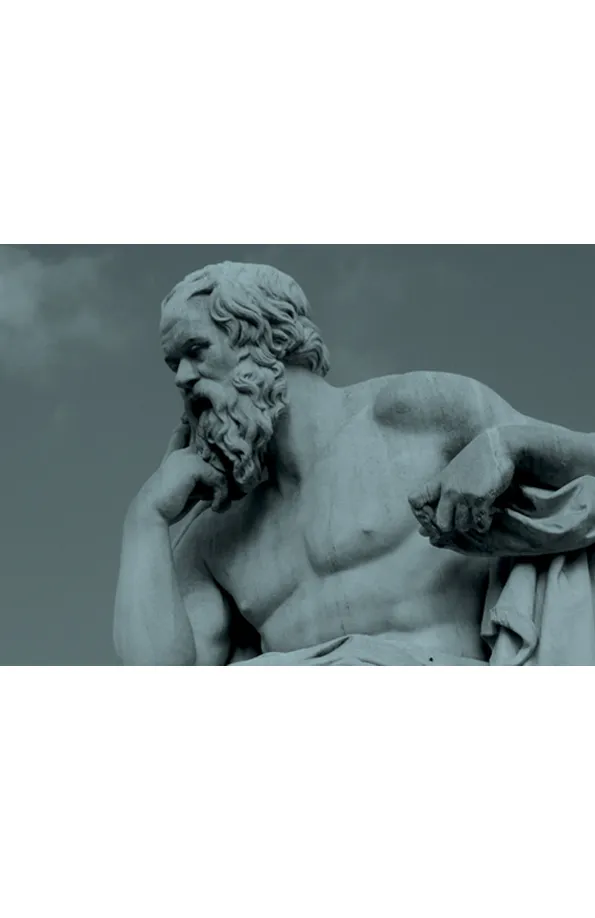

Know yourself

SOCRATES, the earliest and greatest of Western philosophers, summed up the purpose of philosophy in one simple phrase: ‘know yourself’. In giving this motto such importance in his thought, Socrates was alluding to a big problem with being human: we normally don’t know ourselves very well, although, fatefully, we might feel as if we do. The spotlight of consciousness usually only shines on a small part of what is really going on inside us. We are governed by forces we rarely pay attention to: envy, disavowed anger, buried hurt, ideas from childhood that have come to frame our outlook but that we hardly realise we possess. The consequences of this ignorance are typically disastrous. As an antidote, Socrates advocated the regular, careful examination of our minds. He recommended systematically asking ourselves, ideally in the company of a patient and thoughtful friend, questions like: what are my priorities? What do I really fear? What do I truly want? Investigating and interpreting our thoughts and feelings was, and remains, the essence of what it means to be a philosopher.

Philo-sophia

IN ANCIENT GREEK, philo means love, sophia wisdom. Quite literally, a philosopher is someone with an unusually powerful love of wisdom. The concept of wisdom can sound abstract and lofty, but it isn’t. We can and should all strive to be a little wiser. The wise are, first and foremost, realistic about how challenging many things can be. They are fully conscious of the complexities entailed in any project. They rarely expect anything to be wholly easy or to go entirely well. As a result, they are unusually alive to moments of calm and beauty – even extremely modest ones. The wise know that all human beings, themselves included, are never far from folly. Aware that at least half of life is irrational, they try – wherever possible – to budget for madness, and are slow to panic when it rears its head. The wise know how to laugh at the constant collisions between the noble way they would like things to be, and the demented way they often turn out.

Eudaimonia

THIS IS AN ANCIENT GREEK WORD, normally translated as ‘fulfilment’, particularly emphasised by the philosopher Aristotle. It deserves wider currency because it corrects the shortfalls in one of the most central terms in our contemporary idiom: happiness. The Ancient Greeks resolutely did not believe that the purpose of life was to be happy; they proposed that it was to be fulfilled. What distinguishes happiness from fulfilment is pain. It is eminently possible to be fulfilled and, at the same time, under pressure, suffering physically or mentally, overburdened and in a tetchy mood. Many of life’s most worthwhile projects will, at points, be quite at odds with contentment, but may be worth pursuing nevertheless. Henceforth, we shouldn’t try to be happy; we should accept the greater realism, ambition and patience that accompanies the quest for eudaimonia.

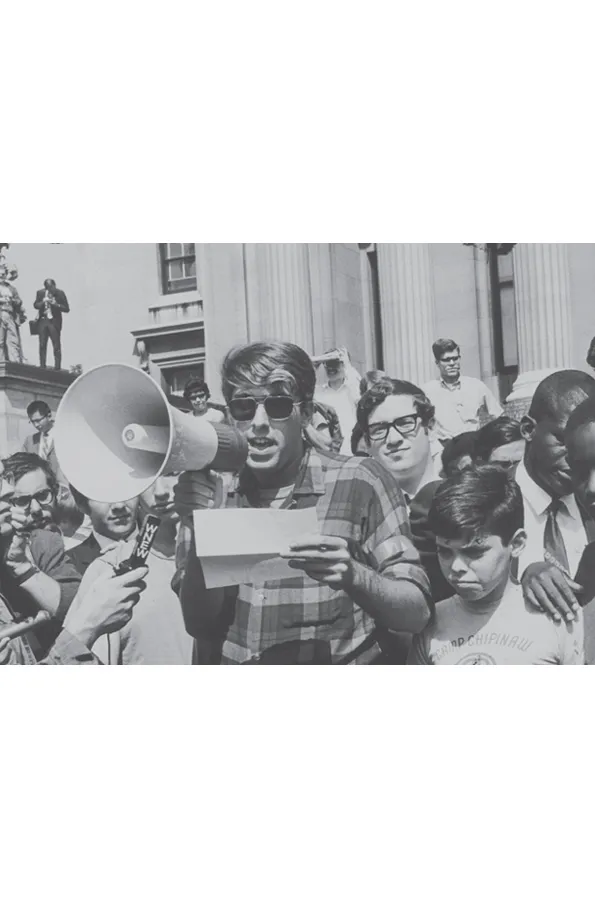

Democracy

DEMOCRACY IS A BEAUTIFUL IDEA: everyone’s vote is equal, whatever their income or education. It feels wicked to say anything against it. Yet democracy is obviously a touch unreasonable – and the Greek philosophers knew it. Plato said so most clearly in The Republic: it is impossible that every person’s view can be equally astute. A democratic vote is like the captain of a ship having to consult every passenger about the best course to chart through an approaching storm. For admirable reasons, we are committed to a political system that is problematic. According to Plato, the solution should be intense universal education to foster wisdom in everyone. We cannot allow everyone to vote until everyone has learnt to think. Till then, we need to laugh at the tragi-comic nature of our predicament. There will be a lot of erratic choices. The Ancient Greek philosophers – whom we mistakenly believe all loved democracy – had a clear-eyed view of the many problems that might crop up. After all, they invented the word ‘demagogue’ to describe a political leader who, in a democracy, sweeps into power by collecting votes through appeals to the lower passions rather than to higher reason.

Eros and philia

VERY EARLY ON, GREEK PHILOSOPHY TWIGGED that love is not really one thing but a cluster of very different emotions and attitudes that we should carefully distinguish between. Having an array of words for love can spare us the perils of a simple-minded sense that we are no longer ‘in love’ when we’ve merely moved onto a different, but still authentically real, phase of love. The Greeks anointed the powerful physical feelings we often experience at the start of a relationship with the word eros. But they knew that love is not necessarily over when this sexual intensity wanes, as it almost always does. It can evolve into another sort of love, which they beautifully captured with the word philia. This is normally translated as ‘friendship’, although the Greek word is far warmer, more loyal and more touching; one might be willing to die for philia. Aristotle recommended that we outgrow eros in youth, and then base our relationships – especially our marriages – on philia instead. The word adds an important nuance to our understanding of a viable union. It allows us to see that we may still love even when we are in a phase that our own blunter vocabulary fails to recognise.

‘What need is there to weep over parts of life? The whole of it calls for tears’

THE ROMAN PHILOSOPHER SENECA used to comfort his friends – and himself – with this darkly humorous remark. It gets to the heart of Stoicism, the school of philosophy that Seneca helped to found and that dominated the West for 200 years. We become weepy and furious, says Stoicism, not simply because our plans have failed, but because they have failed and we strongly expected them not to. Therefore, thought Seneca, the task of philosophy is to disappoint us gently before life has a chance to do so violently. The less we expect, the less we will suffer. Through the help of a consoling pessimism, we should strive to turn our rage and tears into that far less volatile compound: sadness. Seneca was not trying to depress us, just to spare us the kind of hope that, when it fails, inspires bitterness and intemperate shouting.

Peccatum originale

IN THE LATE 4TH CENTURY, as the immense Roman Empire was collapsing, the leading philosopher of the age, St Augustine, became interested in possible explanations for the tragic disorder of the human world. One central idea he developed was what he legendarily termed peccatum originale: original sin. Augustine proposed that human nature is inherently damaged and tainted because, in the Garden of Eden, the mother of all people, Eve, sinned against God by eating an apple from the Tree of Knowledge. Her guilt was then passed down to her descendants and now all earthly human endeavours are bound to fail because they are the work of a corrupt and faulty human spirit. This odd idea migh...