![]()

1 | A radical history of development studies: Individuals, institutions and ideologies

UMA KOTHARI

Why a radical history of development studies?

This book provides radical, historically informed readings of the emergence, trajectories and interpretations of international development. It presents a critical genealogy of development studies through exploring changes in discourses about development and examining the contested evolution and role of development institutions by focusing upon the recollections of those who teach, research and practise development. These accounts challenge the dominant, modernist narrative that posits a singular, unilinear trajectory and present alternative versions of ideas and institutions, and the people that embody them. The book shows how the work of individuals and institutions engaged in contemporary development studies cannot be properly understood without adequate historical contextualization. Accordingly, the chapters presented in this volume will attempt to understand why and how international development, generally, and development studies, specifically, have evolved.

This is a radical chronicle because it includes plural conceptions of development history and adopts a critical perspective towards, and engagement with, orthodoxies of development theory and practice. Each chapter, moreover, is radical in at least one of two other senses – first, by highlighting those concealed, critical discourses that have been written out of conventional stories of development or marginalized in mainstream accounts of ideas that have influenced contemporary understandings of development thought; second, in that their critique of ideas and practices of development is founded upon, and emerged out of, thinking from the ‘left’. In this book these radical interpretations are represented by, for example, Marxist, post-colonial and feminist perspectives and analyses.

With a few notable exceptions the history often rehearsed in development research and teaching has tended towards a compartmentalization of clearly bounded, successive periods characterized by specific theoretical hegemonies that articulate a singular theoretical genealogy. Typically, the story commences with economic growth and modernization theories, moves on to discuss theories of ‘underdevelopment’, and culminates in neo-liberalism and the Washington Consensus (see Hettne 1995; Preston 1996). This periodization, moreover, is mapped on to particular events and processes, most notably with the reification of 1945 as the key year in which development was initiated owing to the establishment of the World Bank and other Bretton Woods institutions. Recent critical explorations, from post-colonial, postmodern and feminist perspectives, have undoubtedly provided important challenges to orthodox development chronologies but they have to varying degrees continued to conform to the same periodization (Marchand and Parpart 1995; Rist 1997; Kothari and Minogue 2001), as have those that present alternative visions of development (Munck and O’Hearn 1999; Rahnema and Bawtree 1997). To counter these trends and develop the longer historical perspectives and alternative readings of the origins and evolution of development taken by Jonathan Crush (1995) and Cowen and Shenton (1996), the chapters in this book highlight how bounded classifications and epochal historicizations not only obscure a longer genealogy of development but also undermine attempts to demonstrate historical continuities and divergences in the theory and practice of development, compounding the concealment of ongoing critiques. They underscore how this limited analysis reveals the largely unreflexive nature of the field of study, partly engendered through the imperative to achieve development goals and targets.

By providing different understandings of the growth of development studies, this book subverts a mainstream unilinear history and moves beyond a periodization of theoretical positions. More broadly, by using development studies as a case study, some of the chapters challenge ideas about discourse and power by questioning particular notions of what constitutes development and the ‘Third World’, and interrogate our understandings of the interrelationship between what Stuart Hall (1996) refers to as the ‘West and the Rest’. In critiquing orthodox ideas, challenging normative representations and highlighting both continuities and divergences over time and across space, they disrupt the projection of a singular record of the past. These understandings are essential to identify how the present is informed by the past and to further recognize that history can enable a (re)visioning of future strategies for change.

While the importance of reflexively tracing the evolution of their disciplines has recently been acknowledged by some within, for example, anthropology and geography, understanding the implications of the past is not a mainstream preoccupation within development studies. This volume represents an attempt at exploring the history of development studies as a multi-disciplinary subject that emerged in the post-war era of decolonization, but was also informed by antecedent influences. It takes a multi-methodological and holistic approach by weaving together different narratives, including personal recollections of working in development studies, histories of particular themes, such as gender, social development and natural resources within development studies, and genealogies of development institutions such as the World Bank. Some of the chapters redirect attention towards ideas, ideologies and concepts in a field that for some time has been characterized by more practical and technical concerns. The insistence on the link between past and present, and adopting a radical appreciation of a range of perspectives, will (it is hoped) mark a significant moment in the critical reconfiguration of development studies.

Understanding development studies

Understandings of the nature and concept of development studies are as varied, multiple and contentious as definitions of what constitutes development itself. Indeed, particular perceptions of what constitutes development studies are linked to, and often embedded in, particular notions about what development is.

That development studies is open to varying and contesting interpretations is evident from ongoing discussions among those in relevant academic departments, institutions and associations. There are diverse views concerning what development studies is or should be, ranging from opinions as to whether it is primarily about academic research or more concerned with policy and practical relevance, whether it possesses a specific epistemology and methodology, and the extent to which it is multi-disciplinary, inter-disciplinary or cross- disciplinary. These contesting points of view reflect competing understandings about the purpose of development and the nature of the relationship between theories and ideologies, policies and practices. Furthermore, they highlight the various insights into, and perspectives on, the genealogy of development.

Significantly, these issues have cohered around debates on the distinctiveness of development studies as a field of academic study. There is general agreement that development studies cannot claim to be a distinct and separate academic discipline in the same way as, for instance, economics or geography, partly because it is a relatively new field of study. Rather it is cross-disciplinary, engaging with different bodies of theory, conceptual and methodological frameworks, and understandings of policy relevance and practical implications. It is this borrowing and application of ideas from different disciplines that to some extent provides the distinctive characteristics of development studies. A series of articles in World Development (2002) explores this issue of cross-disciplinarity, a generic term relating to forms of analysis that are substantially based on theories, concepts and methods of more than one discipline (see Kanbur 2002). Inter-disciplinary partnerships have proved difficult to achieve, however, and development studies can be more accurately described as multi-disciplinary. Although various disciplines are brought together in development studies and share the same academic space, and despite attempts to identify its epistemological and methodological distinctiveness (see Sumner and Tribe 2004), there has been limited success in producing truly hybrid theories, methodologies or practices.

While development studies cannot be identified as a discrete academic discipline there is a broad convergence among those in the ‘community’ on shared concerns and objectives. For example, there is some agreement about what the object/subject of study should be and what foundational theories and concepts students of development should be familiar with. Most commonly, development studies is seen to be concerned with processes of change in so-called ‘Third World’ or ‘developing countries’, and more recently this has been widened to encompass transitional economies. For some, there is also a narrowing of focus on studies of poverty and poverty alleviation while others have become increasingly concerned with socio-economic dimensions of global inequities and exclusionary processes. There remains, however, an ongoing debate as to the overwhelming importance of practice in relation to theory. In a paper on the irrelevance of development studies, Michael Edwards (1989) directly addresses this issue and argues that research within development studies is often abstract and divorced from development in practice and the realities of poor people. Thus, he contends, to understand development problems requires being involved in the process of development itself, thereby strengthening the links between research and action. The continuing relevance of this debate about research and practice is, in part, engendered by the legacy of the original context of post-independence development studies. When many development studies institutes were first established, those involved were primarily concerned with policy formulation and the technical and practical measures required to implement economic and social change, and accordingly spent much of their time overseas. This theory/practice divide, or what Sumner and Tribe (2004) refer to as the divergence between ‘discourse-related’ and ‘instrumental/empirical- oriented’ categories of development studies, has become exacerbated as alternative strands in development studies are increasingly uneasy with what is seen as the over-emphasis on planning change without significant identification and critique of the ideologies that underpin these standard policies and practices.

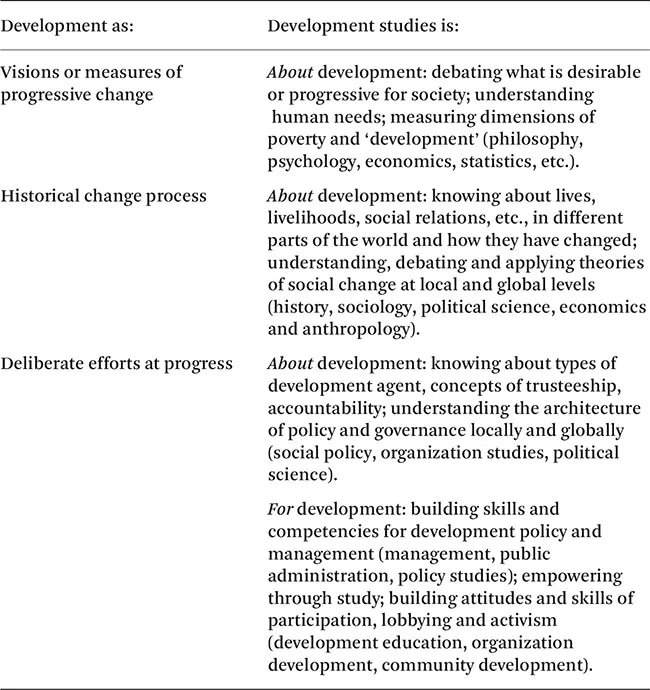

To clarify these points, Alan Thomas (2004) suggests that as the definition of ‘development’ adopted varies, so does the viewpoint concerning what development studies is about or for. His typology of the relationship between ideas about development and ensuing definitions of development studies, which is presented below, explores further this issue of what should be studied and from what viewpoint.

It is the interrelationship between theories, ideas and histories of development policy and practice which makes the identity of development as a subject of study so complicated and contested. There are those who feel that the study of development is most closely connected to ideas about social, economic and political change, while others are informed by a more instrumental goal of shaping policy and a practical concern with the implementation and evaluation of development interventions. Thus, there is disagreement as to where development studies should be located along a continuum from intellectual analyses and interpretations of processes of change to ‘doing development’ utilizing the practical skills and techniques associated with transformation on the ground. Those who draw a parallel with the emergence of social policy as an academic discipline suggest that influencing, formulating and implementing policy must guide development studies. For example, Raymond Apthorpe suggests that development studies should be thought of as poverty or policy studies, and that ‘changing from Development Studies to Poverty Studies offers an opportunity to incorporate ideas and methodologies from other disciplines into the social analysis of poverty’ (1999: 535). These reflections on analysing and doing development – or about and for development – are at the heart of attempts to define development studies.

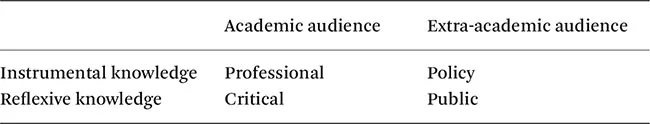

Michael Burawoy’s (2004a) thought-provoking article on the disciplinary division of labour in sociology is particularly useful to those wrestling with the dilemmas involved in identifying coherent yet diverse development studies. Burawoy identifies four interdependent sociologies – policy, professional, critical and public – and makes the case that these are not ‘alternatives but necessary complements’. He constructs a disciplinary matrix, reproduced below, while acknowledging that the boundaries between the different fields are often blurred, individuals can have multiple interests, and priorities vary between academic institutions, and over time.

Burawoy (2004b) contrasts different audiences and different forms of knowledge and suggests that professional and policy work are primarily instrumental forms of knowledge ‘inasmuch as they are concerned with orienting means to given ends, namely puzzle solving in professional research that takes for granted the presumptions of a given research program, and problem solving in the policy arena that takes for granted the goals and interests of the client’. He envisages critical and public fields as reflexive forms of knowledge that are oriented ‘to a dialogue about assumptions, values, premises’ among those in the discipline and with the public.

Applying this sort of disciplinary matrix to development studies could provide a useful starting point for identifying and appreciating the interconnectedness of the diverse range of activities, and perspectives, that come under its rubric. A discussion of this kind is imperative given the shifting local and global context in which development currently takes place. The chapters in this book, in various ways, contribute to this debate by demonstrating, for example, that development studies is not only about describing and understanding planned interventions but also about analysing discourses of development and seriously interrogating processes of socio-economic, political and institutional change. Not all contributors see their research as having direct policy and practical relevance but rather as providing the very necessary critiques and analyse...