1

Current Matters

An Introduction

Pictures want equal rights with language, not to be turned into language. They want neither to be leveled into a “history of images” nor elevated into a “history of art,” but to be seen as complex individuals occupying multiple subject positions and identities.

—W.J.T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want?

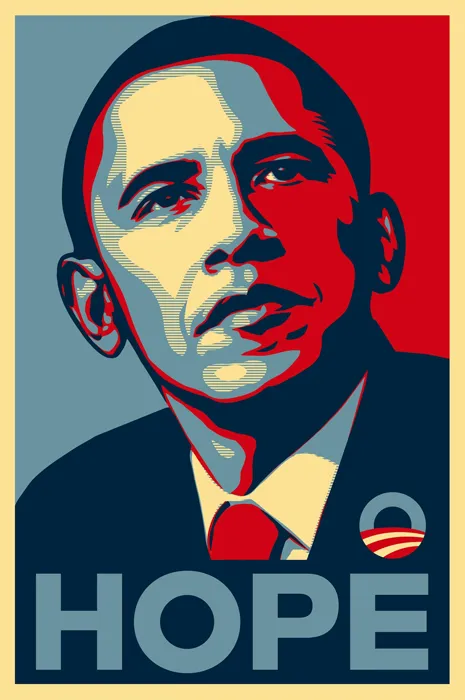

April 27, 2006, is an important date for visual rhetoric. On this date, Hollywood actor George Clooney, Senator Sam Brownback, and then-Senator Barack Obama were holding a press conference at Washington’s National Press Club. Clooney had just returned from a trip to Darfur and was publicly demanding that the US government act more quickly to stop the ongoing genocide. On the sidelines a photographer for the Associated Press (AP) sat, intending to capture photos of Clooney in an important political performance. Little did the photographer know, when he turned his camera toward Obama, that he would capture one of the most iconic images to surface in recent US history.

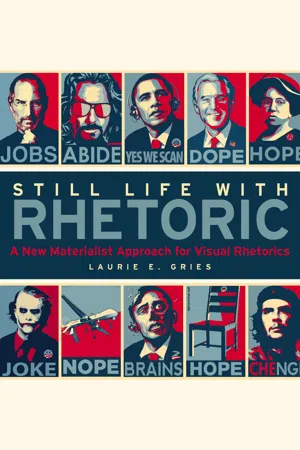

The photograph taken by Mannie Garcia is now familiar to those of us who closely followed the 2008 US presidential election, have paid attention to US popular culture over the last few years, or have simply passed the image captured in the photo on the street one day while walking to work. For the image in Garcia’s photograph transformed into the now-iconic Obama Hope image designed by street artist Shepard Fairey (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2). The Obama Hope image in its “Faireyized” version (henceforth referred to as simply Obama Hope) entered into circulation in late January 2008 in an effort to help then-Senator Obama become the 44th US president. Today, digital manifestations and remixes of this image can be found on more than two million websites while numerous physical renditions can be found tattooed on human bodies, plastered to urban walls, and waving at protests across the globe. As it has circulated both within and beyond US borders, this image has played a plethora of rhetorical roles ranging from political actor to advertising agent to social critic to international activist. Today, its materialization in Fairey’s Hope poster is also widely recognized as a cultural icon and national symbol. New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl (2009) has gone so far, in fact, as to deem Fairey’s Hope poster the most efficacious political illustration since Uncle Sam Wants You.

How has this particular image come to lead such an extraordinary rhetorical life? How did it go from materializing in one among hundreds of photographs taken at a press conference in April of 2006 to a cultural icon, national symbol, and powerful rhetorical actant in just a few short years? When asked how the Obama Hope image gained the wide recognition needed to become a cultural icon, Fairey himself said the image simply “went viral.” Made popular with the boom of the Internet in the mid-to-late 1990s, “going viral” is a common means of explaining how ideas, trends, objects, videos, and so forth spread quickly, uncontrollably, and unpredictably into, through, and across human populations. Such explanation is linked to a ubiquity of tropes and concepts related to epidemiology that has become part of the US American social imaginary in the twenty-first century. As Chad Lavin and Chris Russill (2010, 67) have argued, this imaginary has manifested in response to an anxiety constituted, in part, by a destabilized sense of space and time produced by an unprecedented emergence of global economic and communicative networks. Deeply entrenched, this epidemiological imaginary can be thought of as “the logic of the viral,” which helps makes sense of not only the spread of diseases but also the spread of culture in a networked social landscape (Seas 2012, 6). According to this logic, a thing is commonly said to be viral when it is perceived as being socially contagious due to its capacity to garner mass attention and spread via word of mouth and media. In common parlance, then, we say something like a video has gone viral based on the sheer speed at which the video has attracted a wide viewing, often, but not always, because it has circulated widely across media, been remixed, and inspired imitative spinoffs.

In an attempt to explain how something such as Obama Hope can go viral, Fairey explained in a Terry Gross (2009) interview on Fresh Air that a viral phenomenon is made possible by first creating an image that is highly desired and admired, and second, by ensuring that a broad audience has access to that image so it can be redistributed. The Internet makes viral campaigns especially possible as images and messages can reach audiences dispersed across the world in a matter of seconds. With the recent emergence of YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and other social-media sites, the capacity for an image and message to circulate widely has only been amplified. Thus, as an explanation of how the Obama Hope image has become a cultural icon, “it went viral” might seem like an easy-enough-to-understand answer. This answer, however, offers little theoretical and practical understanding of how images actually circulate, transform, and replicate in both physical spaces and cyberspace. In an increasingly participatory culture in which a variety of groups produce and distribute media for their collective interests (Jenkins, Ford, and Green 2013, 2), such an answer particularly elides the logics, structures, practices, collectives, and platforms that enable images to circulate and transform widely. This answer also offers little understanding of how things become rhetorical as they circulate and transform with time and space and contribute to collective life. From a new materialist perspective, things become rhetorically meaningful via the consequentiality they spark in the world. By accepting Fairey’s explanation of how Obama Hope has become a cultural icon, then, we miss the opportunity to learn how an image such as Obama Hope becomes an important rhetorical actor as it materializes and actually effects change in our daily realities. Or in simpler terms, by accepting the explanation of “it went viral,” we miss learning how Obama Hope has made and continues to make (rhetorical) history.

In one sense, this book is an attempt to get at these how inquiries. Chapters 6–9 present a four-part case study that makes visible how, since 2006, Obama Hope has influenced cultural, political, and economic materialities and thus, in Bruno Latour’s (2005a) terms, “reassembled the social.” However, while this book may begin with a focus on the Obama Hope image and spend much time throughout discussing its rhetorical life, throughout most of the chapters, Obama Hope ironically acts as a representative anecdote in that the theories and methods included herein have been constructed around the Obama Hope phenomenon.1 In addition, alongside other images such as the Mona Lisa and the Raised Fist, Obama Hope acts as an example to help accomplish the book’s ulterior purpose. As Brian Massumi (2002) draws on Giorgio Agamben to note, the example is an “odd beast” (17). The example is one singularity among others, yet, simultaneously, the example “stands for each of them and serves for all.” As a singularity, the example is neither general nor particular. It belongs to itself and simultaneously extends to everything else with which it might be connected (17–18). As both a representative anecdote and an “odd beast” in this book, then, while the Obama Hope image tells its own unique rhetorical story, the image also exemplifies what we can learn by taking a new materialist approach to studying the futurity of visual rhetoric. For another important purpose of this book is to articulate what a new materialist approach to visual rhetoric might entail and how it might contribute to rhetorical and circulation studies at large.

New Materialism

First coined as a term in the latter half of the 1990s and independently of one another by Rosi Braidotti and Manuel De Landa, new materialism or neomaterialism is an emergent interdisciplinary theory informed by contemporary scholarship emanating from the intersections of science studies, feminist studies, and political theory.2 From a definitional standpoint, new materialism is difficult to pin down. In one sense, new materialism is not new at all in that new materialists build on the work of scholars such as Spinoza, Bergson, Deleuze, and Guattari and can thus simply be thought of as an extension of a longstanding monist tradition (Dolphijn and der Tuin 2012, 94–95). Furthermore, new materialism is not a unified shared inquiry, especially since it is being taken up across multiple fields such as political science, women’s studies, social science, history, and, as of late, rhetorical studies. Nonetheless, new materialism can be thought of as part of a nonhuman turn3 taking place across several disciplines as scholars challenge the modernist paradigm (heavily influenced by Descartes and Kant) that perpetuates dualist kinds of thinking, which many scholars find reductive and unproductive. As Latour (1993) explains in We Have Never Been Modern, modernity tries to divide the world into separate, opposing spheres with humans/subject/culture on one side and things/objects/nature on the other. New materialists reject such dualism, arguing that any bifurcation of humans and things, culture and nature, object and subject fails to acknowledge the ontological hybridity that constitutes reality. In order to make sense of the complex material realities we face in the twenty-first century, then, new materialists focus on what Donna Haraway (2003) has called “naturecultures,” or what Latour (1993) calls “collectives,” to acknowledge the significant, active role nonhuman things play in collective existence alongside a host of other entities.

New materialism, in part, is an ontological project in that it challenges scholars to rethink our underlying beliefs about existence and particularly our attitudes toward and our relationships with matter. In a broad sense, new materialists conceive of matter as vital, transformative, and morphogenetic; in this sense, as Tianen and Parikka (2010) have argued, matter is both “self-differing and affective-affected.” New materialism is also a philosophical project as it works to develop new concepts that can help develop new insights about collective matters. In any tradition of inquiry, a common discourse is needed so scholars can communicate and build on each other’s knowledge. As such, new materialists are developing a lexicon filled with neologisms such as intra-action4 and new concepts such as body multiple5 that push us to think otherwise about matters we tend to take for granted. Yet new materialism is also a method...