![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Colorado Climate, Geology, and Hydrology

CLIMATE AND TOPOGRAPHY

Introduction

The nature of a society is determined, at least in part, by the attributes of the natural setting in which it develops. To understand the story of Colorado water law, one must first explore the windswept peaks, cathedral forests, and sweeping plains that form the state’s landscape. One must meet a mountain stream swollen with snowmelt in a high meadow and follow it down the mountain, through the foothills, and across the broad plain to the horizon. One must look beneath the surface of the earth at the vast, silent formations of rock and sediment, formed in ages past, now holding vast amounts of water suspended in pores and cracks within the rocks. This chapter looks at the constraints and opportunities presented by Colorado’s climate, topography, hydrology, and geology.

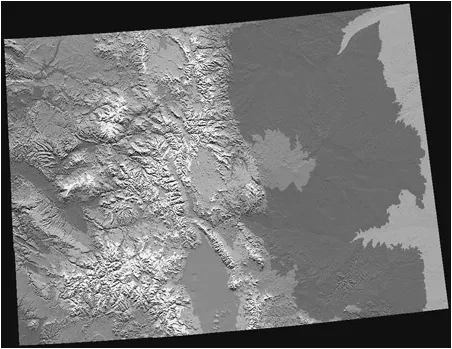

1.1 Colorado shaded relief map. Courtesy of the U. S. Geological Survey

Colorado is a very large state—the eighth largest of the fifty U.S. states—with 104,000 square miles within its borders. Many nonresidents have a preconceived vision of Colorado as composed of wall-to-wall mountains, sparkling rivers, and snow-covered ski resorts from Julesburg to Rifle. That vision is abruptly altered as one drives along Interstate 76 in northeastern Colorado, passing vistas of sagebrush, prickly pear cactus, and unending treeless prairie. Approximately 40 percent of Colorado’s land area is located in the relatively flat Eastern High Plains. The remaining landscape is almost equally divided between the Central Mountains and the Western Plateaus. Mountains, plains, mesas, and plateaus all combine to make up Colorado (Figure 1.1).

Colorado’s climate is one of extremes. For a sportsperson, a good spring day could involve a round of golf in the morning and downhill skiing in the afternoon—both at world-class resorts. What makes this possible is Colorado’s diverse climate, which is shaped by its unique location and topography. According to the Ground Water Atlas of Colorado, five major factors combine to produce different, localized climates in the state: (1) latitude, (2) distance from large bodies of water, (3) elevation, (4) topography, and (5) winter storm track position.1 Average seasonal temperature and precipitation vary tremendously across Colorado. The mile-high topography varies from a low elevation of 3,315 feet, where the Arikaree River flows out of eastern Colorado into northwestern Kansas, to a high of 14,433 feet on the peak of Mt. Elbert (almost 3 miles above sea level). Average elevation is 6,800 feet above sea level and includes fifty-three mountains with elevations of 14,000 feet or more.2 Colorado has more mountains with peaks in excess of 14,000 feet than all other states combined. Mile high indeed!

STATE LINES |

Colorado is one of only three states (Wyoming and Utah are the other two) that generally follow lines of latitude and longitude for all its borders. State lines extend from 37 degrees N to 41 degrees N and from 102 degrees W to 109 degrees W. |

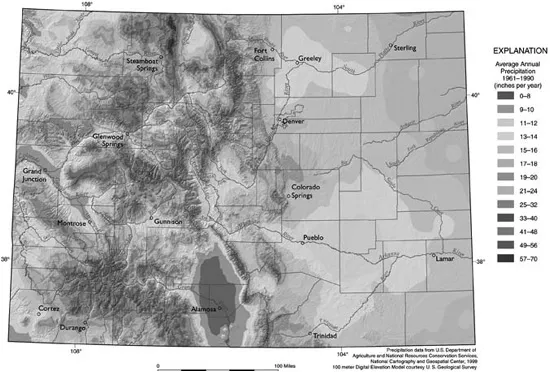

Although towering mountains are poised to grab passing moisture from the atmosphere, Colorado’s average annual precipitation is only seventeen inches. This is somewhat misleading, however, because elevation and topography create great regional extremes across the state. For example, the San Luis Valley in south-central Colorado is a high mountain desert that receives about seven inches of average annual precipitation, while the nearby San Juan Mountains receive over forty inches of precipitation each year. Extreme variability in rain and snowfall—with occasional droughts thrown in—presents serious challenges to water managers and users and has created the setting for Colorado’s unique and expansive water law system. Figure 1.2 shows the average annual precipitation across Colorado.

1.2 Average annual precipitation. Reprinted from the Ground Water Atlas of Colorado, Special Publication 53, by Ralf Topper and others, ©2003, with permission from the Colorado Geological Survey.

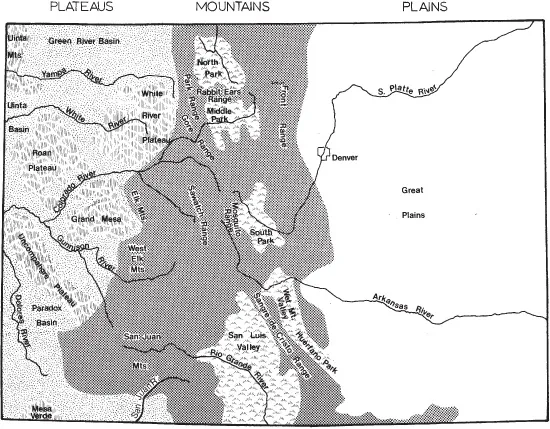

1.3 State’s three major regions (reprinted from J. V. Ward and B. C. Kondratieff’s An Illustrated Guide to the Mountain Stream Insects of Colorado, Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1992)

Colorado can be divided into three general areas, from east to west: Eastern High Plains, Central Mountains, and Western Plateaus (Figure 1.3).

Eastern High Plains

The Eastern High Plains of Colorado are vast and sometimes brutal. Large regions of rolling grassland extend westward from Kansas and Nebraska, rising gently about 1,000 feet in elevation to meet the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in the central portion of the state.

Precipitation on the semiarid Eastern High Plains averages between 12–16 inches per year. Much of it occurs in a few scattered, violent summer thunderstorms or dangerous spring blizzards. In repayment for this violent weather, the region has abundant sunshine, low relative humidity, wide-ranging daily temperature variations (including relatively cool summer evenings), some wind, and dry spells that last for weeks and sometimes months at a time. Colorado’s Eastern High Plains embrace a raw beauty that is timeless.

Two of eastern Colorado’s major river systems, the South Platte and the Arkansas, originate as coldwater streams high in the Rocky Mountains. From an alpine terrain of spruce and pine, melted snow trickles toward the expanding urban Front Range cities. The Arkansas River proceeds east past Pueblo, while the South Platte River carves a path through Denver. Indirectly, even lazily at times, these two rivers continue for 200 miles across the Eastern High Plains toward the flatlands of Kansas and Nebraska.

STEPHEN HARRIMAN LONG |

Major Stephen Harriman Long (Figure 1.4) was selected by President James Monroe to lead the 1820 expedition to explore areas acquired in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Major Long was born in 1784 in Hopkinton, New Hampshire, the youngest of thirteen children. He was a graduate of Dartmouth College and taught for two years at the U.S. Military Academy before exploring the future state of Colorado. |

Major Long’s expedition was instructed to locate the headwaters of the South Platte, Arkansas, and Red rivers. He followed the Platte River (the same route taken by Interstate 80 across Nebraska today) and then the South Platte River (generally following the future route of Interstate 76 in northeastern Colorado). Long’s twenty-man expedition included a geologist, a zoologist, a botanist, a mineralogist, a surgeon named Edwin James, and artists Samuel Seymour and Titian Peale (who was also a naturalist). |

This was a military expedition of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. It reached Colorado’s Front Range in July 1820 and traveled to and named Long’s Peak. The group then traveled upstream along the South Platte River through the future location of Denver, then down to the Arkansas River watershed. Three members of the expedition, including Dr. Edwin James, climbed Pikes Peak. Later, Long’s group was unable to find the Red River, ran into hostile Kiowa-Apache Indians, and eventually had to eat their horses to survive. |

Fairly recently, the 1819 wintering site of the Long Expedition may have been located on river-bottom farmland north of Omaha, Nebraska, near the mouth of the Platte River.4 Only one of the specimens collected by the expedition remains today—a greater prairie chicken at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Fortunately, a two-volume, 1,000-page report issued by the government is also on display at the academy. |

The region’s elevation begins at around 5,000 feet along the Front Range foothills and gradually declines to about 3,400 feet above sea level at the Kansas border near Holly and at Julesburg near the Nebraska border. Large areas of rolling flatland dominate the region—which caused the expedition of Stephen Harriman Long to call it the Great American Desert. Long’s cartographer wrote this desolate description on a map published in 1823, perhaps for two reasons: (1) to describe the dry nature of the Eastern High Plains, a “barren and uncongenial district”; and (2) to discourage the interest of foreign governments in the area.3

1.4 Stephen Harriman Long (© Colorado Historical Society, painting by Juan Menchaca, Scan #20003045).

Colorado pioneers followed Long’s route in the mid-1800s and commented on the dry condition of the South Platte River during July and August. Winter snows melted in the late spring and filled the South Platte with high flows. Remarkably, a few weeks later the riverbed was dry. This is the historical nature of the South Platte River, as well as the Arkansas River.

Historically as well as today, river flows of the South Platte and Arkansas are greatly affected by summer rainstorms and springtime mountain snowmelt. Approximately 70–80 percent of the region’s annual precipitation occurs during the growing season of April through September.5 However, precipitation extremes can vary wildly. Average annual precipitation for this region varies between 12–16 inches, but during May 1935, for example, nearly 24 inches of rain fell along the Republican River in northeastern Colorado. Extended droughts in the 1930s, mid-1950s, 1970s, and 2002–2003 are stark reminders of the fickle nature of precipitation on the Eastern High Plains.

Central Mountains

The Central Mountains of Colorado are the backbone of North America. These majestic peaks form the Continental Divide, which towers across Colorado from the Steamboat Springs area in the northern part of the state to Pagosa Springs and beyond to the south. The Continental Divide is the highest terrain between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and separates the direction of flowing water in the state. Precipitation that falls on the Eastern Slope of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado ultimately flows toward the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. By contrast, precipitation that falls on the Western Slope of the Rockies flows to the Colorado River, the Sea of Cortez, and the Pacific Ocean.

THE COLORADO RIVER |

The Colorado River is one of the most aggressively utilized rivers in the world. The Colorado River begins at the Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park. By the time the river reaches its last seventy-five miles and the Sea of Cortez (also called the Gulf of California) and the Pacific Ocean, all of its flows have been diverted, consumed, or evaporated. The once mighty Colorado River rarely flows through the Mexican states of Sonora and Baja California; all that remains in these regions is a remnant system of wetlands and brackish mudflats. |

The elevation of the Continental Divide in Colorado is responsible for much of the state’s climatic extremes and changeable weather. Why? Orographic lifting is the reason, as it creates far ...