eBook - ePub

10 Essential Instructional Elements for Students With Reading Difficulties

A Brain-Friendly Approach

Andrew P. Johnson

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

10 Essential Instructional Elements for Students With Reading Difficulties

A Brain-Friendly Approach

Andrew P. Johnson

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Brain-friendly strategies to help all students become lifelong readers This book is the definitive resource on how the brain creates meaning from print. Drawing from five key areas of neurocognitive research, Andrew Johnson provides a ten-point teaching strategy that encompasses vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, writing and more. A key resource for creating intervention plans for struggling readers, features include:

- Information on the importance of emotions in the process of overcoming reading struggles

- Strategies to promote voluntary reading, even for the most reluctant students

- Useful resources such as graphic organizers, additional reading and writing activities, and QR codes that link to videos

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que 10 Essential Instructional Elements for Students With Reading Difficulties est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à 10 Essential Instructional Elements for Students With Reading Difficulties par Andrew P. Johnson en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Bildung et Lernschwierigkeiten. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1 Creating Meaning With Print The Neurocognitive Model

Reading is creating meaning with print.

Over the course of the next three chapters, I will describe the process of reading first from a neurological perspective and then from a cognitive perspective. Understanding the process our brains use to create meaning with text will enable you to design and plan effective reading instruction. As stated in the Introduction, the content contained in these first chapters tends to generate questions and sometimes even controversy. Thus, I have included many more reference citations in these first chapters than I do in later chapters.

Understanding Reading

The Phonological Processing Model of Reading

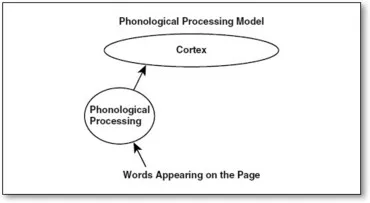

The phonological processing model (described briefly in the Introduction) defines reading as simply sounding out words. According to this model, reading is a bottom-up process. Here information flows one way, from the page (the bottom) through the eyes, to the thalamus, and up to the higher regions of the brain or the cortex (the top) (Figure 1.1). According to this model, our eyeballs move in a straight line from left to right along the page as we perceive, and then process each individual letter in our working memory. Each letter is then converted into a sound, the sounds are pasted together to form words, each word is put into a sentence, and each sentence is then put in the context of a greater idea and comprehended. However, that’s a whole lot of small moving parts to try to assemble in working memory in the microseconds available to us as we read words and sentences.

Based on the phonological processing model, students with reading disabilities are often given a lot of sounding-out instruction with the assumption that this will help them learn to read. These types of phonics-based programs may improve students’ ability to sound out words in isolation, but by themselves, they tend to be minimally effective (Johannessen & McCann, 2009; Strauss, 2011).

Figure 1.1 Bottom-Up View of Reading

The Neurocognitive Model of Reading

The interactive or neurocognitive model defines reading as creating meaning with print. Sounding out words is seen as only part of the process of creating meaning with print. To illustrate, when you hear somebody speak, you perceive the individual sounds of each word and the individual words, but listening in this sense is different from perceiving individual sounds or putting sounds together to form words. To listen here is to ascribe meaning to the message. You pay minimal attention to the individual sounds and words and instead focus on meaning or what these are pointing you toward. Indeed, the sounds and words carry little meaning by themselves. Instead, these are always found within a meaningful context. As you listen, you use semantics (meaning or context), along with syntax (word order and grammar), and background knowledge (schemata) to understand what the speaker is trying to tell you.

Reading is much the same. We use what’s in our head along with the little squiggly shapes appearing on the page to create meaning. Expert readers do not attend to every letter (Paulson & Freeman, 2003; Weaver, 2009); instead, they use minimal letter clues along with context (semantics), the information in our heads (schemata), and syntax to create meaning with print (Binder, Duffy, & Rayner, 2001; Hruby & Goswami, 2013; Rayner & Well, 1996). Right now, as you are reading this page, you are not processing each individual letter. Your eyeballs are actually stopping to focus or fixate on approximately 85% of the content words and approximately 35% of the function words (Rayner, Juhasz, & Pollatestk, 2007). Your eyeballs are making small backward movements (regressions) to refocus on certain content words that may be less familiar to you as well.

Creating Meaning With Print

To illustrate further, take a minute to read the text in Figure 1.2. Notice the difference between reading this and the text in the preceding paragraph. Below your reading was most likely much slower and choppier, your eyeballs made more fixations and regressions, you needed to stop to process and review individual letters, and you sounded out each part of the big words before you put them together. In essence, your reading was very much like that of a struggling reader. And, unless you know Latin, you were not creating meaning with print. Thus, you were unable to use syntax and semantics to try to make sense of this.

Figure 1.2 Sound This Out

Reading: A Neurological Perspective

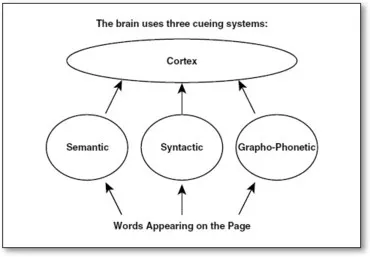

We read with our brain. As we read, our brain is constantly reaching out to fill in the blanks or predict the meanings of words in the sentences we are reading (Hawkins, 2004; Paulson & Goodman, 2008). Words are verified using three cueing systems: (a) semantic, (b) syntactic, and (c) grapho-phonetic (Anderson, 2013; Hruby & Goswami, 2013; Strauss, 2011) (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Three Cueing Systems

The Three Cueing Systems

1. Semantic

The semantic cueing system is the most efficient of the three in terms of speed and space required in working memory to recognize words. Semantics refers to meaning. As you read, you use context and background knowledge to identify words and figure out what the next word might be. For example:

The monkey ate a _ _ _ _ _ _.

You most likely know what the next word is in the sentence above. As your brain read the sentence, it focused on the words “monkey” and “ate.” This narrowed the possibilities of the word to something monkeys eat. Based on your knowledge of monkey stereotypes, cartoons, and Tarzan movies, you most likely inserted the word “banana.” If you did not immediately insert the word “banana,” your brain would have then used the first letter to figure it out. If the word “banana” fit with what went before and after you would have continued. We use the knowledge in our head to predict meanings and confirm meanings or make revisions during the reading process.

The monkey ate a b _ _ _ _ _.

2. Syntactic

Syntax has to do with the grammatical structure of the language. As your brain reads, you also use your knowledge of grammar, sentence structure, word order, tense and plurality, prefixes and suffixes, nouns and verbs, and function words (prepositions, pronouns, etc.) to identify words. This is the second most efficient cueing system.

For example, in the monkey sentence above you focused on the word “monkey” (noun) and “ate” (verb). Your brain knew the missing word had to be a noun of some sort. Using syntax together with semantics you were able to easily fill in the missing word. This is how reading works. Your brain works holistically to create meaning with print.

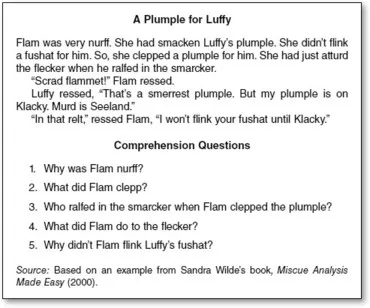

Let me illustrate the idea of syntax further. Read the short nonsense story in Figure 1.4 on the next page and answer the comprehension questions. Even though it is meaningless, you will discover that you can still answer all the questions simply by examining the syntax. (The answers are at the end of this chapter.)

3. Grapho-Phonetic

“Grapho” refers to symbols; “phono” refers to sounds. The grapho-phonetic cueing system uses letter sounds to predict what the next word might be. Of the three cueing systems, this one is the least efficient. Why? Because it focuses on individual letters and letter patterns instead of words and ideas. As you will see in Chapter 3, your working memory has very limited capacity. You can try to stuff a few letters in there, a few words, or a few ideas, but which would be the most efficient in terms of creating meaning with print? An idea is much bigger than a letter. There are far more things contained in an idea than in a letter.

Figure 1.4 Using Syntax to Create Meaning

The Relative Unimportance of Letters

Letters are not nearly as important as you might think. Figure 1.5 contains a short email message that I sent to students in one of my literacy classes at Minnesota State University, Mankato. I kept the first and last letters the same but scrambled up the inside ones. Are ...