eBook - ePub

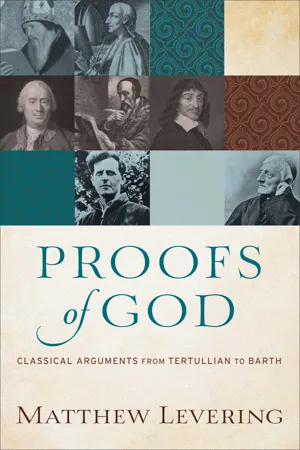

Proofs of God

Classical Arguments from Tertullian to Barth

Levering, Matthew

This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Proofs of God

Classical Arguments from Tertullian to Barth

Levering, Matthew

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Leading theologian Matthew Levering presents a thoroughgoing critical survey of the proofs of God's existence for readers interested in traditional Christian responses to the problem of atheism. Beginning with Tertullian and ending with Karl Barth, Levering covers twenty-one theologians and philosophers from the early church to the modern period, examining how they answered the critics of their day. He also shows the relevance of the classical arguments to contemporary debates and challenges to Christianity. In addition to students, this book will appeal to readers of apologetics.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Proofs of God est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Proofs of God par Levering, Matthew en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Theology & Religion et Christian Theology. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

Theology & ReligionSous-sujet

Christian Theology1

Patristic and Medieval Arguments for God’s Existence

In her The Divine Sense: The Intellect in Patristic Theology, A. N. Williams points out that for fathers of the church, humans after the fall continued to possess the light of reason. The fathers ruled out any “pessimistic apophaticism” or any effort “to impugn our capacity to know God, at least dimly,” because such views “would amount to claiming God had deliberately left us bereft of the only means to good, happy and purposeful lives, and would deny, therefore, any conceivable telos to creation.”1 In this chapter, I show that the fathers of the church, along with almost all medieval theologians, held that humans can rationally demonstrate the existence of God.

I focus on four fathers and three medievals. In Tertullian, we find the same proof that Xenophon attributed to Socrates: the ordered cosmos could not have made and governed itself. Tertullian insists that Christianity does not introduce a new God: despite the fall, the majority of humans already knew God, even though they also worshiped other gods. There is a human yearning for God that also testifies to God’s existence. Gregory of Nazianzus demonstrates God’s existence in three ways: through the order of the universe, through the fact that every finite thing is dependent and cannot move the whole, and from finite perfections to infinite perfection. He compares the universe to a beautiful lyre and to such things as birds’ nests and bees’ honeycombs. The universe cannot account for its order, movement, existence, and perfections, as Gregory also shows in his poetry. Augustine makes much of human desire for God, as well as the contingency of all things. His favorite demonstration of God’s existence has its starting point in the soul’s intellectual light, which discerns (as the measure of all truth) an immutable, eternal Light—eternal truth, goodness, and beauty. Like Tertullian, Augustine argues that almost all humans prior to Christ knew of the existence of a supreme Creator God, despite their idolatry. Augustine grants, however, that even when humans are aware that God is that than which there is nothing better, humans can falsely imagine that finite things are the highest, despite the fact that nothing merely living can be as good as infinite Life. John of Damascus offers various demonstrations of God’s existence, including from the fact that changeable things require a source, from the order of creation whose disparate elements could not otherwise hold together, and from the fact that things cannot spontaneously come to be and preserve themselves in being.

Turning to the medieval period, I first discuss Anselm of Canterbury. In his Monologion, Anselm demonstrates God’s existence from our desire for good, from the fact that existing things require a self-subsistent source of existence, and from degrees of perfection. But Anselm is most famous for the demonstration that he offers in his Proslogion, which begins with Augustine’s definition of God as that than which nothing better exists. Anselm argues that once we understand the terms of this definition, we can show that God must indeed exist. Gaunilo responds to Anselm, arguing that Anselm has conflated the order of knowing with the order of being; in turn, Anselm responds to certain errors that Gaunilo makes in his presentation of Anselm’s ideas. Thomas Aquinas is best known for his adaptation of the Aristotelian proofs from motion (or change), from efficient causality, and from contingency. He also sets forth demonstrations based on the degrees of perfection and the order of the universe. Although we find similar proofs in the fathers, Aquinas gives a more metaphysically detailed exposition of each proof. He adds an explanation of why Anselm’s proof in the Proslogion does not work. The last figure treated in this chapter, William of Ockham, does not think that the demonstrations from motion or efficient causality work, but he does argue that human reason can demonstrate God’s existence on the basis of the universe’s conservation in being. Ockham denies, however, that human reason can demonstrate the unity of God, thereby throwing into doubt whether human reason can demonstrate God’s existence even from the universe’s conservation in being.

It should be clear that this chapter covers a wide terrain. Most of the fundamental kinds of demonstrations of God’s existence appear in this chapter, and also, in Ockham, the first significant doubts about their efficacy. Let us now turn to the writings of these seven seminal contributors to the Christian tradition of demonstrating the existence of God.

Tertullian (ca. 150–ca. 220)

A native of Carthage and a married layman, Tertullian was a lawyer who was well educated in philosophy and rhetoric. An author of numerous seminal theological and ascetical works, he is known for developing much of the Latin terminology for the theology of the Trinity. Tertullian is sometimes thought to have separated from the church toward the end of his life. Although he adhered to the prophecy of Montanus and admired its moral rigor, Tertullian at least technically remained within the church, because during his lifetime the church in North Africa had not yet expelled the followers of Montanus’s prophecy. Later North African bishop-theologians, notably Cyprian of Carthage and Optatus of Milevis, held Tertullian in high regard. Augustine read Tertullian carefully and was deeply influenced by him, although he criticized him for teaching that second marriage was forbidden and for founding separatist congregations.2

In his Apology, after describing the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire and criticizing at length the worship of the gods, Tertullian begins his defense of Christianity by proclaiming the one God: “The object of our worship is the One God, He who by His commanding word, His arranging wisdom, His mighty power, brought forth from nothing this entire mass of our world, with all its array of elements, bodies, spirits, for the glory of His majesty.”3 Tertullian describes this God as invisible, incomprehensible, and infinite. Even when we know him, he remains unknown. Humans, however, can and should know him, and humans who fail to know and worship him are culpable.

In this light, Tertullian goes on to offer two ways of demonstrating the existence of God.4 First, we can demonstrate that God exists on the basis of the existence and order of the cosmos. Tertullian appeals to the fact that such a vast, well-ordered cosmos cannot have made and governed itself. He terms this “the proof from the works of His hands, so numerous and so great, which both contain you and sustain you, which minister at once to your enjoyment, and strike you with awe.”5 The second proof comes from the soul and is based on human experience. Although we are often enslaved to our bodily desires, when our soul wakes up from this enslavement we find ourselves yearning for God. As evidence of this yearning and of our knowledge of the One for whom we yearn, Tertullian points to the frequency of reference to “God” (deus) in common pagan speech. Looking toward the heavens, humans often praise God or appeal to God for help and for justice. The soul looks up to God and knows God must exist.

At this juncture, Tertullian...