![]()

PART 1

Where Higher Life Theology Came From and What It Is

Before we can responsibly evaluate higher life theology (part 2), we must understand it. We must listen before we critique. So part 1 tells the story of where higher life theology came from (chap. 1) and explains what exactly it is (chap. 2).

![]()

CHAPTER 1

What Is the Story of Higher Life Theology?

When I first heard people preach and teach higher life theology, I didn’t know anything about its story. My pastors and other teachers claimed the Bible teaches higher life theology, so I initially assumed that they were right and that Christians have always embraced it. Learning its history was a liberating step for me. I realized that this view is novel—that it is relatively new in the history of Christianity. It is also just one of several competing views about Christian living.

There are at least five major views that evangelicals hold on the Christian life.1 At the risk of oversimplifying them, five figures presented throughout this book attempt to graphically depict those views of Christian living, which theologians call views of sanctification (see figs. 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, 2.4, and 3.8).2

This chapter tells the story of higher life theology by answering three main questions:

1.Where did higher life theology come from?

2.Who initially popularized higher life theology?

3.What are some influential variations on higher life theology?

The story begins with John Wesley.

1. WHERE DID HIGHER LIFE THEOLOGY COME FROM?

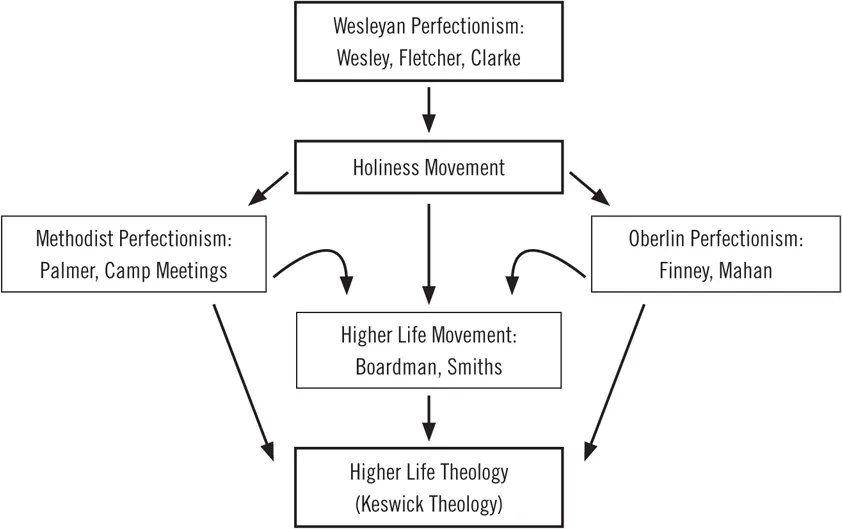

Figure 1.1 illustrates where higher life theology came from:

Fig. 1.1. Where Did Higher Life Theology Come From?

Higher life theology has two main influences: Wesleyan perfectionism and the holiness movement.

WESLEYAN PERFECTIONISM: PERFECT LOVE TOWARD GOD AND HUMANS

The Wesleyan view of progressive sanctification has a lot in common with higher life theology. John Wesley (1703–1791) is the father of views that chronologically separate the time a person becomes a Christian from the time sanctification begins.

Wesley taught “Christian perfection,” which he qualifies does not refer to absolute sinless perfection.3 Christian perfection is a type of perfection that only Christians can experience—as opposed to Adamic perfection, angelic perfection, or God’s unique, absolute perfection. The way Wesley qualifies Christian perfection hinges on how he narrowly defines sin as “a voluntary transgression of a known law.” He limits “sin” to only intentional sinful acts. He admits that “the best of men” commit “involuntary transgressions,” for which they need Christ’s atonement, but he can still call such people perfect or sinless. When one defines sin that way, Wesley does not object to the term “sinless perfection,” but he refrains from using that term because it is misleading.4

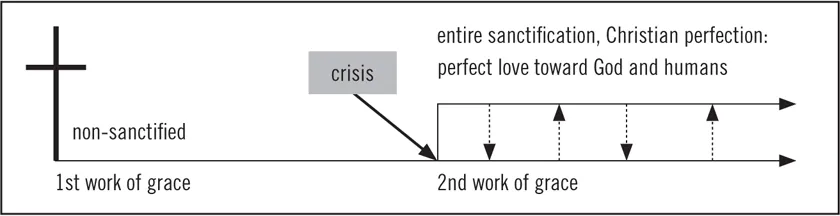

The essence of Wesley’s Christian perfection is perfectly loving God with your whole being and, consequently, perfectly loving fellow humans. Christian perfection occurs at a point in time after you are already a Christian. Wesley labels this second work of grace as not only Christian perfection but salvation from all sin, entire sanctification, perfect love, holiness, purity of intention, full salvation, second blessing, second rest, and dedicating all your life to God (see fig. 1.2).5

Fig. 1.2. The Wesleyan View of Sanctification

Two of Wesley’s followers significantly developed his doctrine of Christian perfection. John Fletcher (1729–1785) used “Pentecostal” language to describe how Christian perfection begins the instant a believer experiences the outpouring of the Spirit, is baptized with the Spirit, is filled with the Spirit, or receives the Holy Spirit as the promise from the Father. Adam Clarke (1762–1832) used Fletcher’s “Pentecostal” language to emphasize the crisis of Christian perfection more than both Wesley and Fletcher.

THE HOLINESS MOVEMENT: MODIFIED WESLEYAN PERFECTIONISM

When Wesleyan perfectionism blended with American revivalism, the holiness movement emerged. The holiness movement began in the late 1830s and modified the views of Wesley, Fletcher, and Clarke. Two significant parts of the holiness movement were Methodist perfectionism and Oberlin perfectionism.

Methodist perfectionism emphasized the crisis of Christian perfection more emphatically than Wesleyan perfectionism. The person most responsible for that was Phoebe Palmer (1807–1874). Her “altar theology” promised “a shorter way” to holiness.

The term altar theology comes from the first step of Palmer’s popular three-step teaching: You must entirely consecrate yourself or totally surrender by offering yourself and all you have on the altar (Rom 12:1–2). Christ is the altar (Exod 29:37; Heb 13:10), and the altar sanctifies the offering (Matt 23:19). When you entirely consecrate yourself, you are instantly and entirely sanctified.

Palmer used “Pentecostal” language to emphasize the crisis of Christian perfection, which she argued results in power for serving God. Her views became popular through her writings and through holiness camp meetings that began in New Jersey in 1867. During these holiness camp meetings, revivalists pressed people to choose to experience the crisis of entire sanctification.

Oberlin perfectionism is similar to Wesleyan perfectionism, but it distinctively views sanctification as entirely consecrating a person’s au...