![]()

Jörgens V, Porta M (eds): Unveiling Diabetes - Historical Milestones in Diabetology. Front Diabetes. Basel, Karger, 2020, vol 29, pp 115–133 (DOI: 10.1159/000506558)

______________________

Historical Development of Oral Antidiabetic Agents: The Era of Fortuitous Discovery

Harold E. Lebovitza Yves Bonhommeb

aDepartment of Medicine, State University of New York, Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA; bPast VP R&D Groupe Lipha, Lyon, France

______________________

Abstract

The development of antidiabetic agents prior to 2000 was largely the result of fortuitous discovery coupled with insightful clinical acumen. Many years intervened between the chance discovery and the development of marketable clinically important products. The first hint that biguanides might be useful in managing diabetes was noted in the early 1900s; however, metformin did not achieve worldwide use and recognition as the first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes until the late 1990s. The hypoglycemic potency of sulfa drugs was first noted in 1942, but the introduction of sulfonylurea drugs to treat patients with type 2 diabetes occurred in 1956. Defining their mechanisms of action did not occur until the 1990s. The elucidation of the profound effects of thiazolidinediones through their activation of the transcription factor PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma) came many years after the discovery of ciglitazone. It is of note that in the development of each of these classes of antidiabetic drugs, regulatory agencies struggled with controversial data and made decisions which had profound effects on their clinical use.

© 2020 S. Karger AG, Basel

The development of drugs to treat diabetes mellitus in general, and type 2 diabetes in particular, can be divided into two eras: the first in which drugs were found through serendipity, and the later in which basic science had unraveled the pathophysiology of diabetes sufficiently to provide the basis for developing new targeted pharmacologic agents. The first era occurred from the early 1900s through to 2000 and provided for the development of biguanides, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones. The mechanisms of action of these drugs were defined well after they were being used clinically. The second era was from 2000 through to the present day and provided for the development of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) enhancers and receptor agonists as well as sodium glucose transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i). The later class of drugs were developed after their basic physiologic effects were known to potentially ameliorate some of the pathophysiology of diabetes. Here, we focus on the circuitous and difficult development of the early and still extremely useful oral antidiabetic agents.

Fig. 1. The plant G. officinalis (goat’s rue). From Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé: Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz, 1885, Gera, Germany.

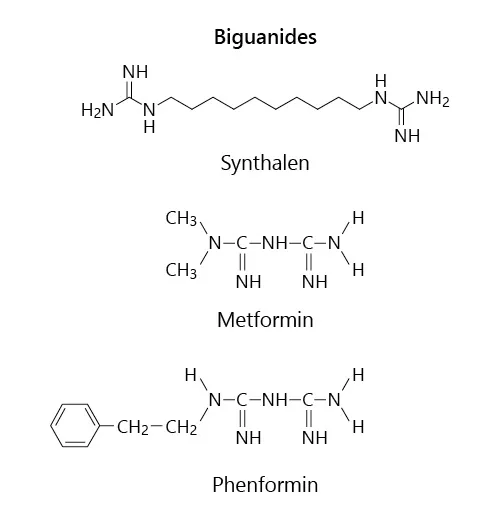

Fig. 2. The major guanidine derivatives that were developed for clinical use: synthalin, metformin, and phenformin.

Biguanides and Metformin

Guanidine Derivatives: From Plants to Synthalins

In traditional medicine, more than 400 plants have been described as treatments for diabetes mellitus, but few of them have been scientifically evaluated. At least two contain guanidine derivatives, Ilex guayusa, used by Amaguajes Indians in the Andean Amazon, and Galega officinalis, the goat’s rue (Fig. 1) [1]. In 1910, Kossel [2] in Germany showed that agmatine (4-aminobutyl guanidine) extracted from herring sperm caused hypoglycemia. In 1918, Watanabe [3] in America assumed that tetany following parathyroidectomy was hypoglycemia and was due to elevated guanidine. He injected rabbits with guanidine chlorhydrate and induced hypoglycemia and convulsions. In 1914, Georges Tanret [4] isolated galegine (iso-pentenyl-guanidine) from fabacean, a monoguanidine compound. Thirteen years later, with the aim of developing an insulin substitute, Tanret demonstrated the hypoglycemic effect of galegine in dogs and rabbits. Although the margin between the dose inducing the hypoglycemic effect and the one causing lethal convulsions was narrow, he administered galegine sulfate to healthy men and confirmed an effect on reducing both fasting and postprandial glycemia. Müller and Reinwein [5] in Germany, and Rathery and his intern Jean Sterne in France successfully treated patients with diabetes with this drug, but stopped their experiments since the patients had severe side effects and a rapid loss of efficacy [5, 6]. Ten years later, Frank et al. [7] in Germany confirmed these results in that they modified the guanidine molecule in order to maintain the hypoglycemic effect with less toxicity. In 1927 they developed a diguanidine, Synthalin A (decamethylene-diguanidine; Fig. 2) and tested it in diabetic patients [8]. This oral treatment for diabetes was well accepted by many diabetologists [9, 10]. However, severe complications, including nephritis, acute hepatitis, and bone marrow alterations, had begun to be observed [11]. The London Royal Society of Medicine commissioned a group of experts to review the Synthalin A data and they concluded that its side effects precluded its use as a treatment for diabetes [12]. Synthalin A was described as a poison inducing high lactate blood levels, inhibition of liver glycogen synthesis, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea and, at high doses, liver necrosis. Furthermore, synthalin-associated hypoglycemia could not be corrected by glucose infusion. Frank and Wagner suggested using another diguanidine compound, Synthalin B or neosynthalin (dodecamethylene-diguanidine), which was described as less toxic. This product was only used in Germany until 1945. Even though Hesse and Traubmann [13] reported the hypoglycemic effect of metformin in 1929, the spectacular failure of synthalin discredited all guanidine derivatives for more than 20 years and froze any research in this field.

Fig. 3. Jon Aron (left) owned Laboratories Aron, and Jean Sterne (right) was the chief research scientist. From Lipha Historical Files, public domain.

Metformin Development in France (The Aron Odyssey)

After the Second World War, as a result of research to treat malaria, Curd et al. [14] developed a new biguanide, paludrine (N1-p-chlorophenyl-N5-isopropylbiguanide), which was effective and well tolerated. In 1947, Chen and Anderson [15] reported that this biguanide had a weak hypoglycemic effect. During the flu epidemic of 1949 in the Philippines, flumamine (dimethylbiguanide) was used as a treatment and was well tolerated [16]. Flumamine was the same molecule synthesized by Werner and Bell [17] in 1922 and is the same molecule as metformin (Fig. 2). Jan Aron, a French pharmacist, and Jean Sterne, a research scientist and part-time diabetologist at Laennec Hospital in Paris, at Laboratoires Aron recognized that some biguanides were well tolerated and had some hypoglycemic activity (Fig. 3). Although hypoglycemic sulfonylureas were on the market, Jean Sterne recognized the need for additional treatments for diabetes mellitus and tested the hypoglycemic activity and toxicity of different biguanides. Metformin was less active than phenformin, but it had the best activity versus toxicity ratio of the biguanides tested and was chosen as a drug candidate for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Pharmacological studies were carried out in several animal species, including alloxan and streptozotocin diabetic dogs. Metformin showed a weak activity with a narrow toxic margin in non-diabetic animals, whereas in diabetic animals hypoglycemic activity was seen with lower doses and the therapeutic safety margin was greater. Longer-term toxicity studies in rats, rabbits, and dogs were conducted in 1957–1958 and confirmed the safety of metformin. Convinced of its good therapeutic margin, Jean Sterne administered metformin to healthy volunteers and patients with diabetes. Observing a good hypoglycemic activity with patients with diabetes, but a weak effect on healthy people, Sterne [18, 19] concluded that metformin is not a hypoglycemic agent but an anti-hyperglycemic one. He gave it the name Glucophage (the glucose eater). Elie Azerad, a diabetologist at the Beaujon Hospital in Paris, conducted the first large clinical trial with Glucophage, including 88 hospitalized patients badly controlled by insulin [20]. The results were considered to be excellent or satisfactory for 78% of the patients (vs. 60% with sulfonylureas in another study). Digestive troubles were reported in 13% of the cases. These results were published in April 1959. In the 1950s, the procedure to market a drug in France required only a Health Ministry visa and that was obtained in December 1958.

Hospital diabetology departments introduced Glucophage into their therapeutic treatment programs. Some pioneers of the clinical use of metformin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes were Paul Rambert, Jacques Chabot, Jean Lebon, Roger Deuil, Jean Vague, and Gérard Debry in France, and Pierre Levèbvre in Belgium. In February 1960, a small representative team was set up to visit general practitioners. Sulfonylureas were the well-established oral treatments for type 2 diabetes, and it was difficult to convince physicians of the value of metformin. It was suggested to each of them to test Glucophage with 1 of their patients badly controlled by sulfonylureas, thanks to numerous communications at international congresses. Several publications by Sterne [21, 22] reviewed the clinical data and the results of 5 years of treatment with metformin of patients with type 2 diabetes. Glucophage caught the interest of diabetologists and clinical studies wer...