![]()

PART ONE

SAN JUAN RIVER EXPEDITION

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Preparation and Start

On a sunny July day in 1921 H. Elwyn Blake, Jr., twenty-four, left the back room of the San Fuan Record, the weekly newspaper at Monticello, Utah, where he worked as a part-time printer. A cool breeze off the Abajo Mountains to the west ruffled his sandy brown hair as he walked toward the drugstore on Main Street. He was sucking the side of his hand to ease a fresh burn from the infernal linotype machine. At the drugstore he took a seat at the counter and was sipping a root beer when some dusty men walked in and sat down at a side table.

Turning to look at them, he saw a big fellow in faded bib overalls who seemed familiar, someone he had worked with before the war. Five years had passed, though, so he was not quite sure. The group sat down and ordered ice cream, then one of them cranked up the phonograph and put on a record. As music filled the room, the man in the overalls laid down his spoon and listened quietly. Then Elwyn was sure. The only person he had ever known who would stop eating to listen to good music was Bert Loper.

Elwyn grinned as he walked over and said, “Bert, how are you?”

The man looked up, thrust out his hand and exclaimed, “You old desert rat. I thought I should know you. Come sit down.”1

Bert Loper was almost fifty-two years old, a miner by trade. He had spent much of his life in rough country and as a result was strong in body and somewhat crusty in temperament. In the 1890s he had tried placer mining on the San Juan River and had his first boating experience there.2

Elwyn had met Loper while working for a placer outfit at North Wash in the Henry Mountains in south-central Utah. It had been Elwyn's first job after graduating from high school at Green River, Utah. He had been assigned to work on a ditch being blasted to the placer site. Bert Loper was the powderman-foreman of the ditch project. He suffered headaches when handling dynamite, so he sat in the shade while directing Elwyn on how to do it. Loper was the same age as Elwyn's father. Both were born in 1869, the year that Major John Wesley Powell first explored the Grand Canyon. Still, Loper and Elwyn had taken to each other from the start. Loper liked Elwyn because he was a good worker and because he would stand up to him in an argument. Elwyn enjoyed Loper's tales of the mining camps. Later they worked together as part of a survey crew on the San Rafael Desert and again in the Robbers Roost area. Elwyn even camped at Lost Spring for a while with Loper and his wife Rachel.

That was all before Elwyn went to Europe to fight in World War I. Now he was back home in Monticello but not satisfied with his humdrum life. In the drugstore, as the two friends talked of old times, Loper suddenly asked, “Do you want a job?”

“If it's outdoors I sure do,” Elwyn replied. “I'm fed up with inside work.”

“It's outside, all right,” Loper said. He explained that he and his companions were heading for the San Juan River at Bluff, Utah, to survey that river's canyons down to the Colorado. He said, “A couple of applications are in ahead of yours, but the boss will listen to me. Your survey work on the desert would help.”

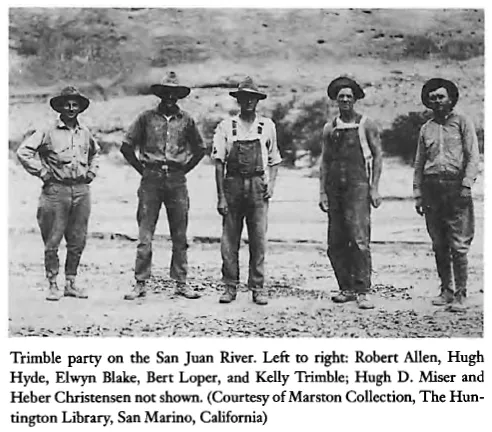

Loper introduced Elwyn to Kelly Trimble, topographical engineer for the United States Geological Survey, who was in charge of the crew that would map and explore the San Juan River Canyon. With him was Robert Allen from Los Angeles, California, the survey recorder.

Kelly Trimble had hired Bert Loper as head boatman for the expedition because of his boating experience and knowledge of the San Juan River. Loper was serving as rodman on the first leg of the work. He was to pick up an elevation at Moab and run the line to a point on the San Juan River several miles below the town of Bluff, Utah.3 Trimble, Allen, and Loper had stopped in Monticello.4

Elwyn landed the job as rodman. A few days later, on July 17, 1921, he began the trip perched on the back of a truck headed south toward Bluff.5 The truck carried two boats, equipment, supplies, and crew members of the expedition. Elwyn spent the time visiting with Loper and getting acquainted with the others. He would not sleep under a roof for the next five months.

The expedition was a joint effort of the United States Geological Survey and the Southern California Edison Company. Robert N. Allen, the recorder, was a civil engineer representing the power company. The Edison Company had ordered the boats made in San Pedro, California, and had shipped them by rail to Green River, Utah. Trimble had purchased food staples and other supplies in Salt Lake City, had shipped them by rail to Green River, and had hired a truck to haul them and the boats on to Bluff.6

Heber Christensen, a tall, bilingual Mormon from Moab who had grown up on the Navajo Indian reservation at Tuba City, Arizona, had signed on as cook. He was thirty-eight and had spent some time on the San Juan River during the oil boom.7 His knowledge of the Navajo language would come in handy before the trip was over.

Hugh D. Miser, from Arkansas and Washington, D.C., a geologist for the United States Geological Survey, joined the party at Monticello. He was overweight but would lose some pounds before the trip was over. He would be a cohesive force in the party during the expedition.

Hugh Hyde, a lanky twenty-one-year-old Mormon descendant of one of the early settlers of Bluff, joined them there as rodman. This completed the party of seven.

On Monday, July 18, 1921, the party arrived at the launch site four miles below Bluff, the present site of Sand Island picnic area where float trips are now launched. The truck was unloaded by about 10:00 A.M. They slid the boats down a steep place in the bank and eased them into the shallow water. Miser noted, “4412 elevation of terrace on side of San Juan just north of launching locality.”

Loper looked the duffel over and found much more than the boats could safely carry. He proceeded to sort out extra clothes, suitcases, and other unnecessary things. This upset some crew members, but Trimble backed Loper, relying on his boating experience and knowledge of the river. Even then the two small boats could carry barely enough supplies to last until the party would reach Goodridge (now Mexican Hat).

Trimble sent the surplus provisions by truck to Goodridge for storage until needed. The excess baggage was loaded on the truck addressed to various homes.

Elwyn Blake wrote in his autobiography:

We had two sixteen-foot skiffs, about sixteen inches deep, with probably a four foot beam. The boats would be used mainly for transportation of supplies and equipment, but occasionally both men and equipment had to be transported. On these occasions the boats sat very low in the water.8

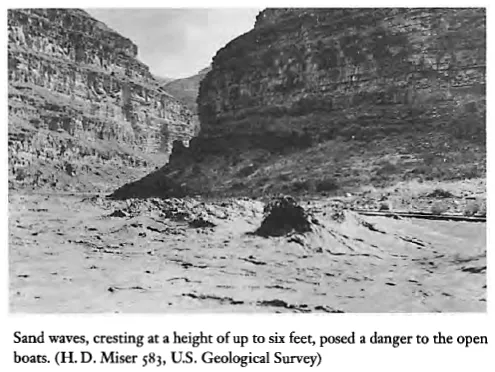

They had the boats loaded by lunchtime. Christensen, the cook, was supposed to help Loper move camp with the boats. The two pushed off at 12:45 P.M., Loper in one boat and Christensen in the other. Before they had gone far, sand waves began to take form ahead of them. Loper, in the lead boat, kept his craft headed straight into them.

Sand waves were something new to Christensen. The waves grew higher and higher, then began to comb with their roaring back-curl. This was too much for him. He panicked and quit rowing. When Loper looked back to see how Christensen was doing, he was disgusted to see the boat wallowing out of control. He rowed to it, tied the painter to the seat of his own boat, and towed Christensen to shore. He vowed then never to let Christensen row a boat again.

Unlike most rivers, sand waves occur frequently in the San Juan. They only form in swiftly moving streams when the silt load is heavy and contains just the right combination of suspended clay and sand particles. When the gradient of the riverbed flattens a little, sand particles settle along the bottom forming ripples that grow into dunes. These sand dunes are called anti-dunes, and they grow higher and higher causing corresponding waves on the surface of the stream. In time the anti-dunes build too high and are washed out, only to build again. The waves break upstream before them and roar before flattening out. This is known as combing. Miser tells us:

The usual length of sand waves, crest to crest, on the deeper sections of the river is 15 to 20 feet, and the height, trough to crest, is about 3 feet. However, waves of at least 6 feet were observed. The sand waves are not continuous, but follow a rhythmic movement. Their appearance, as seen on the lower San Juan, is as follows: At one moment the stream is running smoothly for a distance of perhaps several hundred yards. Then suddenly a number of waves, usually from 6 to 10, appear. They reach full size in a few seconds, flow for perhaps two or three minutes, then suddenly disappear. Often, perhaps half a minute before disappearing, the crests of the waves go through a combing movement, accompanied by a roaring sound.9

After the encounter with sand waves, Loper took Christensen into his own boat. He rowed one boat and led the other for the three or four miles they had left to go. At the mouth of Comb Wash they started to make camp but quickly moved to another spot when they discovered the area was home to millions of black ants. Loper and Christensen would be together for most of this trip, but after the incident with the sand waves there would be no real comradeship between them. With Loper, if one did not do his job, he just did not matter.

From the launch site Elwyn and the survey team traveled on foot carrying the survey along the right side of the river while Miser explored and made geologic notes. At Mile Three they saw steps in the cliff carved long before by the “Anasazi.”10 Loper had seen these steps at an earlier time and described them to Elwyn as “too steep for me to climb.”

At Butler Wash they saw a small cliff dwelling, and just below that they came to a grand tapestry of petroglyphs in the desert varnish (a dark stain composed of manganese) of the cliff face.11 One panel had the figures of several desert bighorn sheep, the largest one much lighter in color and perhaps more recent than the others.

A bigger panel depicted large, square-shouldered, necklace-clad figures standing among what seemed to be lesser beings. The larger figures appeared to be wearing stacks of halos over their heads. They also looked like they might be blowing smoke rings off to the side. Elwyn wondered what story the ancient writings might tell if he could only decipher their meaning. Don Baars and Gene Stevenson, in their San Fuan Canyons: A River Runner's Guide, say, “The large, square-shouldered figures are believed to be ‘Kachinas,’ or gods, who are given rank by the stripes over their heads and may be seen to be giving speeches by the ‘sound waves’ marked beside their heads.”12 Don Keller, an archaeologist who has worked in this area, says that “Kachina panel” is a misnomer since the petroglyphs here predate the Hopi Kachina cult by centuries. They can be thought of as proto-Kachinas.

A couple of miles farther on the surveyors came to a widening benchland where they discovered a large cliff dwelling tucked up under an overhang of the orange cliff. Anglos have named it “River House” or “Plumed Serpent” for the pictographs on the rock face there. Again Elwyn wondered about the life of the ancient ones who built it.

Farther down on the same benchland they came to the foot of San Juan Hill. Mormon pioneers had carved a dugway up the rocky side of Comb Ridge in March 1880 on their way to settle the town of Bluff.13 It had taken them several days to blast the mile-long wagon road up the steep sandstone ledges. Aside from Hole-in-the-Rock on the Colorado River, San Juan Hill was the steepest crossing of that pioneer journey. By this time their horses were worn out from the wintry trip on insufficient feed. To make it up the dugway, the pioneers hooked seven span of horses to one wagon, whipping them all the way. If some of the horses were down on their knees, fighting to get up, those on their feet could still pull upward.14

This author hiked up that old dugway in 1987. Near the top is an inscription carved on a rock face by those hardy pioneers. It reads “WE THANK THEE OH GOD.”

On the benchland near the foot of San Juan Hill stood the partial walls of a red sandstone building. These were the only remains of a pioneer trading post built there in 1886 by William Hyde and Amasa Barton, Hugh Hyde's grandfather and uncle. It had been abandoned in 1887 after Barton was killed by a Navajo during an argument over some pawned jewelry.15

From the spine of Comb Ridge one can see the Mule Ear Diatreme located a mile south of the river. Miser photographed this distinctive geologic landmark. The San Juan River meanders through eroded orange and buff sandstone hills in this area, and the shores of several islands are lined with green cottonwoods and willows, a pleasing contrast to the surrounding bluffs.

About six that evening the surveyors reached camp just above the mouth of Comb Wash on the right side. They were hungry and ready for supper. Christensen had set up the camp stove and had the meal nearly ready. The smell of fresh coffee further whetted their appetites. They all washed up in the river while he finished cooking.

After supper the men sat around talking. Christensen began telling stories, a practice he would continue throughout the trip. Elwyn said he entertained them the entire time and never told the same story twice. When one of the men complimented him on the meal, he answered, “The secret of being a good cook is to first get your customers good and hungry.”

Kelly Trimble explained the purpose of the trip—to map the river and look for possible reservoir sites and power possibilities. He said they would also have to survey all side canyons, together with contours up to the 3,900-foot elevation, in order to determine the storage basin of a proposed dam in Glen Canyon.16 Until they reached the 3,900-foot elevation of the river four miles below Honaker Trail, however, they would be concerned only with mapping the traverse of the river. Miser would record geological data along the way.

For a long time after going to bed Elwyn lay gazing at the sky. The stars seemed almost close enough to touch. How lucky he was to have landed this position. Working at the newspaper had been just a job. He preferred being out of doors. Lately he had spent three days a week at the ne...