eBook - ePub

Introducing Global Englishes

Nicola Galloway, Heath Rose

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Introducing Global Englishes

Nicola Galloway, Heath Rose

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Introducing Global Englishes provides comprehensive coverage of relevant research in the fields of World Englishes, English as a Lingua Franca, and English as an International Language. The book introduces students to the current sociolinguistic uses of the English language, using a range of engaging and accessible examples from newspapers ( Observer, Independent, Wall Street Journal), advertisements, and television shows. The book:

-

- Explains key concepts connected to the historical and contemporary spread of English.

-

- Explores the social, economic, educational, and political implications of English's rise as a world language.

-

- Includes comprehensive classroom-based activities, case studies, research tasks, assessment prompts, and extensive online resources.

Introducing Global Englishes is essential reading for students coming to this subject for the first time.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Introducing Global Englishes est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Introducing Global Englishes par Nicola Galloway, Heath Rose en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Langues et linguistique et Linguistique. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Chapter 1

The history of English

The following introductory activities are designed to encourage the reader to think about the issues raised in this chapter before reading it.

The spread of English

Discussion questions

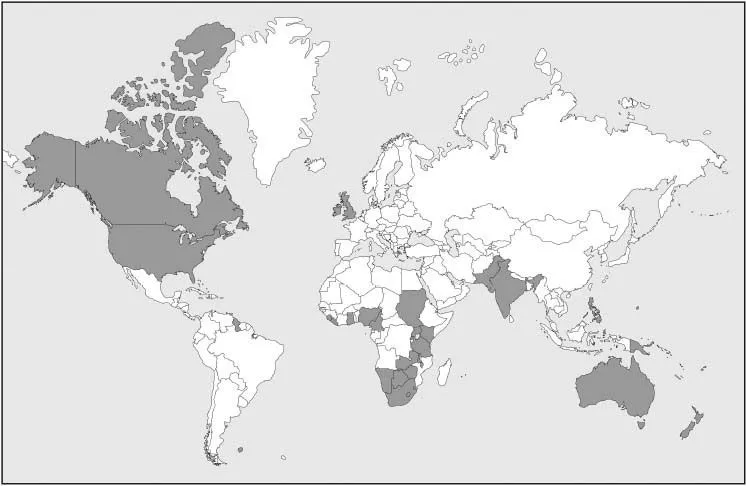

1 As Figure 1.1 shows, English is the official language of many nations across the globe, in all continents.

a How, and why, did English become the official language of so many nations?

2 Mauranen (2012, p. 17) points out that English as a lingua franca is ‘one of the most important social phenomena that operate on a global scale … The emergence of one language that is the default lingua franca in all corners of the earth is both a consequence and a prerequisite of globalisation.’

a How has globalization contributed to the spread of English to regions farther than those highlighted in Figure 1.1?

3 A number of frameworks to represent English speakers around the globe have been proposed, although it is difficult to categorize global English usage (e.g. as a native language or a second language).

a What difficulties might you encounter trying to categorize English speakers? Why is it difficult?

b How would you categorize English speakers from the countries shown in the box below?

Australia, Singapore, Denmark, the USA, China, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Ireland, Brazil, South Africa, Iran, Kenya, India, Mexico.

Case study: problems with classifying English-speaking countries

English speakers are often divided into the Inner Circle (where English is a native language), the Outer Circle (where English plays an important role as an additional or official language, including former Inner Circle colonies), and the Expanding Circle (where English has no official role and is learned as a ‘foreign’ language) (Kachru, 1985, 1992a). India is placed in the Outer Circle, because of its historic ties to the United Kingdom and English’s official status, whereas the Netherlands is placed in the Expanding Circle because English has no official status. However, in India one-sixth of the population is estimated to speak English proficiently (Graddol, 2006), unlike in some Expanding Circle countries, such as the Netherlands and Scandinavian countries, which have much higher proportions of the population (up to 60 or 70 per cent) at a comparable level of proficiency.

Figure 1.1 Countries where English is an official language

Discussion

1 Why do some countries like the Netherlands have higher levels of English proficiency than countries such as India, where English is an official language? How is ‘proficiency’ defined?

2 According to this system of classification, Denmark would be placed in the same category as China, Singapore would be placed with Bangladesh, and Canada (including Quebec) would be placed with the UK. What are the inherent problems with categorizing countries based on colonial history or official use of English?

3 Can you make any suggestions for an alternative system of categorizing?

Further issues related to categorizing English use can be found in Section 1d.

Introduction

This chapter is devoted to exploring the history of English, tracking its development from a language of a small island in Europe to the global lingua franca it is today. Section 1a examines the roots of English in the Germanic languages spoken in the northern regions of Germany and Denmark. It explores the influences of other languages on English, including Old Norse, Latin, and French. Section 1b explores the early dispersal of English around the world, through settler colonization, slavery and trade and exploitation colonies. Section 1b also introduces the effects of this spread on English, a topic explored in greater depth in Chapter 2. Section 1c explores the more recent spread driven by globalization and the journey towards becoming a global lingua franca. Section 1d outlines the state of the English language today, focusing on the number of speakers and learners worldwide and categorization issues.

1a The origins of the English language

Much of this book looks at the implications of the spread of English around the world and the growing use of English as a global lingua franca. However, this first chapter begins with an examination of English through history. In fact, the modern English language has little resemblance to the language spoken in England 1,000 years ago, and almost no connection to the language spoken there 2,000 years ago. This section examines the influences of history and language contact on English, before looking at its dispersal around the world.

The roots of Old English

The people who lived in what is known today as England did not originally speak English. In fact, before the fifth century, the roots of English were not to be found in the languages spoken in Britain. The Ancient Britons, the original inhabitants of the region, spoke a Celtic language. Instead, English has its roots in the languages spoken in the northern areas of Germany and, possibly, the Jutland peninsula in Denmark, which were home to the Saxons, the Jutes, and the Angles (from whom the very word ‘English’ was derived). The spread of these languages to Britain was via the Anglo-Saxon invasion, when Germanic settlers flooded into the region.

However, this was by no means a single organized or unified attack on Britain. Germanic people had been living in England alongside the Britons and Romans for centuries beforehand. It was the power vacuum left there after Roman withdrawal that attracted a large number of invasions from CE 449 onwards, sometimes at the invitation of Celtic kings who were vying to fill the power void (Fennell, 2001). These invasions led to the establishment of seven kingdoms, each with communities of people who spoke vastly different dialects, which pushed the indigenous population into far-flung reaches of the island where remnants of the ancient Celtic languages remain today, including Welsh in the far west, Scottish Gaelic in the far north, and Cornish in the far south-west.

In the following centuries, the languages of these kingdoms were influenced by new settlers and invaders. Old Norse, for example, had a great influence in many parts of Britain due to Nordic invasions, and this influence eventually impacted on the language used throughout the whole region. Despite this variation, by the tenth century it could be claimed that a distinct language called Old English was spoken, albeit unintelligible to an English speaker today, as can be seen from the excerpt from Beowulf, an old heroic poem that is one of the most important works of Anglo-Saxon literature from this period (see Table 1.1).

Norman French and the emergence of Middle English

The English language underwent massive change after the Norman Conquest in 1066. This invasion of England by the Normans saw a French-speaking government established for the following 300 years. As Old Norman (a variety of French) was the language spoken by the kings and nobles ruling England during this time, linguistic features of the language seeped into Old English. McIntyre (2009, p. 12) writes that, ‘Of course, the language did not change overnight, but, gradually, French began to have an influence that was to change English substantially and lead it into its next stage of development – Middle English.’ By 1205, Norman-French domination was replaced by Southern French domination. During the following centuries, English was viewed as the language of commoners, and the speaking of French held status in politics, law, government administration, and noble society.

Table 1.1 Excerpts from literature written in Old English, Middle English and Early Modern English

An excerpt from Beowulf from 900 AD | An excerpt from The Canterbury Tales from 1400 AD | An excerpt from The Hound of the Baskervilles from 1900 AD |

Hwæt wē Gār-Dena in geār-dagum þēod-cyninga þrym gefrūnon hū ðā æþelingas ellen fremedon Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaþena þrēatum monegum mægþum meodo-setla oftēah egsian eorl syððan ǣ rest weorþan | His Almageste, and bookes grete and smale, His astrelabie, longynge for his art, His augrym stones layen faire apart, On shelves couched at his beddes heed; His presse ycovered with a faldyng reed And al above ther lay a gay sautrie, On which he made a-nyghtes melodie So swetely that all the chambre rong; And Angelus ad virginem he song; | Mr. Sherlock Holmes, who was usually very late in the mornings, save upon those not infrequent occasions when he was up all night, was seated at the breakfast table. I stood upon the hearth-rug and picked up the stick which our visitor had left behind him the night before. It was a fine, thick piece of wood, bulbous-headed, of the sort which is known as a ‘Penang lawyer.’ |

During this period, English was an endangered language; the social restrictions on English were indicative of a dying language (Melchers and Shaw, 2011). However, in the later years of French rule, English grew in popularity as it was viewed as a positive symbol of national pride and, eventually, began to replace French as the official language of the nation from 1362, by which time French’s influence on the language had been immense. During the middle ages, more than 10,000 French words entered the English language, particularly surrounding food, politics, and the judicial system (e.g. mutton, pastry, soup, parliament, justice, alliance, court, marriage). Massive grammatical changes also occurred, including the disposal of the gender-based grammatical differences that still remain in most Germanic languages. The result of such massive changes means that a speaker of English today could read a text written in Middle English in 1400 with some assistance, but would be incapable of doing so with a similar text written 400 years previously, as in the example of Old English (see Table 1.1).

The emergence of a ‘standard’ language

The concept of a unified English language began with an increasing need for a language of governance. In the early 1400s, Chancery English was chosen as the ‘standard’ English for handwritten administrative documents in the courts. Chancery English was based on the Midlands variety of English at the time, but was historically influenced by the English used by King Henry V’s private secretariat (Hogg and Denison, 2006). It was chosen as the standard, ‘not only because the Midlands are located in the middle, but because the language was not as extreme as that of the innovative North or as conservative as in the South’ (Gramley, 2012, p. 104). Hogg and Denison (2006) add a few more explanations for the rise of the Chancery English, which would later be referred to as the Chancery Standard. They state:

• the dialect was spoken by the largest number of people;

• the area was wealthy in agricultural resources;

• influential arms of government and administration were located there;

• the area was associated with education and learning, with Cambridge and Oxford universities in close proximity;

• it contained good ports;

• it had strong ties to the church and the Archbishop.

The emergence of a standard written English in the early 1400s, therefore, had much to do with political, social, religious, economic, and educational support. It will become clear in later chapters that such factors have also influenced notions of ‘prestige varieties’ of English in more recent years, and the emergence of a standard language ideology.

Interestingly, the emergence of a definable English language from the late 1400s was, perhaps, less related to this political decision than to a commercial decision by a handful of printers of the time. The invention of Gutenberg’s printing press in the mid-1400s saw Europe go through social and linguistic changes. The printing press saw an explosion of publications in vernacular languages, whereas previous publications were usually carried out in Latin, or in legal languages such as French. As Fennell (2001, p. 157) notes, ‘it rapidly became obvious the English-language books sold better, so that market forces (a modern term applicable to this period) did much to strengthen the position of the vernacular language.’ The printing press for the first time raised the question of what variety of vernacular language to publish in for a mass readership.

William Caxton was one of the first printers to publish texts in English once the printing press was introduced to Britain. In one of his publications he openly discussed the diffi...