![]()

Part I

Archaeology

Studying Ancient Times

Conservation of Sites and Finds

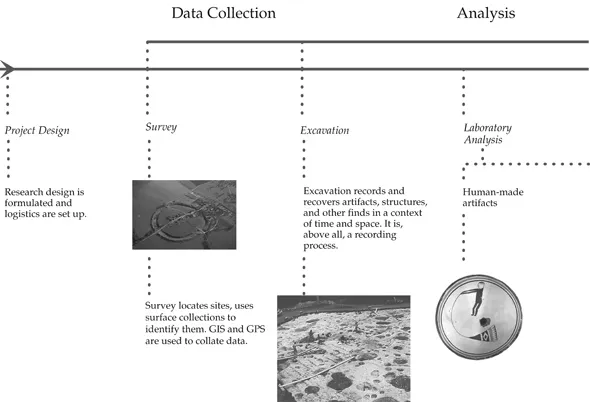

A flowchart shows the process of archaeological research from initial planning to final publication. Conservation is an important concern throughout the project.

![]()

1

Introducing Archaeology and Prehistory

Chapter Outline

How Archaeology Began

Archaeology and Prehistory

Prehistory and World Prehistory

Major Developments in Human Prehistory

Why Are Archaeology and World Prehistory Important?

Who Needs the Past?

The Amphitheater at Epidauros, Greece, fourth century B.C.

The priests supervised the hasty digging of a vast pit in the royal cemetery at Ur in what is now southern Iraq over a few days in 2100 B.C. Dozens of workers carried baskets filled with earth up the ramp and dumped their loads to one side. Next, in the bottom of the hole, a few masons built a stone burial chamber with a vaulted brick roof. A small procession of high officials carried the royal corpse into the empty sepulcher and laid the dead man out in all his finery. They arranged food offerings alongside the bier in gold and silver bowls. Then the dead man’s closest personal attendants knelt silently by their master. They swallowed poison and accompanied the prince into eternity. The walled-up chamber stood at the back of the empty pit, where the priests presided over a lavish funeral feast.

Ur (Ur-of-the-Chaldees), Iraq Biblical Calah, a major city of the Sumerian civilization in the third millennium B.C.

A long line of soldiers, courtiers, and male and female servants filed into the burial pit. All wore their finest robes, most brilliant uniforms, and badges of rank. Each courtier, soldier, or servant carried a small clay cup brimming with poison. The musicians bore their lyres. The royal charioteers drove the ox-drawn wagons down the ramp to their assigned place in the bottom of the great hole. Grooms calmed the restless animals as the drivers held the reins (see Figure 1.1). Everyone lined up in his or her proper place, in order of precedence. Music played. A small detachment of soldiers guarded the top of the ramp with watchful eyes. At a quiet signal, everyone in the pit raised the clay cups to their lips and swallowed the poison. Then they lay down to die, each in his or her correct place. As the bodies twitched and then lay still, a few men slipped into the pit and killed the oxen with quick blows. The royal court had embarked on its long journey to the afterlife.

The priests covered the grave pit with earth and a mud-brick structure before filling the hole and access ramp with layers of clay. A sacrificial victim marked each stratum until the royal sepulcher reached ground level.

Figure 1.1 Reconstruction of a royal funeral at Sumerian Ur, as recorded by Sir Leonard Woolley.

Archaeology is the stuff dreams are made of—buried treasure, gold-laden pharaohs, and the romance of long-lost civilizations. Many people think of archaeologists as romantic adventurers, like the film world’s Indiana Jones. Cartoonists often depict us as eccentric scholars in solar helmets digging up inscribed tablets in the shadow of great pyramids. Popular legend would have us be absent-minded professors, so deeply absorbed in ancient times that we care little for the realities of modern life. Some discoveries, such as the royal cemetery at Ur in southern Iraq, do indeed foster visions of adventure and romance.

British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley reconstructed the Ur funeral from brilliant archaeological excavations made in 1926; the royal sepulchers were a layer of skeletons that seemed to be lying on a golden carpet. Woolley worked miracles of discovery under very harsh conditions. He excavated with only a handful of fellow experts and employed hundreds of workers. When the going got tough, he would hire a Euphrates River boatman to sing rhythmic boating songs with a lilting beat. Woolley cleared 2,000 commoners’ graves and 16 royal burials in four years, using paintbrushes and knives to clean each skeleton. He lifted a queen’s head with its elaborate wiglike headdress in one piece after smothering the skull in liquid paraffin oil. Nearby, he noticed a hole in the soil, poured plaster of Paris down it, and recovered the cast of the wooden sound box of a royal lyre. Woolley reconstructed a magnificent figure of a goat from tiny fragments (see Figure 1.2). He called the cemetery excavation “a jigsaw in three dimensions” and wrote of the sacrificial victims: “A blaze of colour with the crimson coats, the silver, and the gold; clearly these people were not wretched slaves killed as oxen might be killed, but persons held in honour, wearing their robes of office” (Woolley 1982, 123).

Woolley’s excavations captivated the world more than three-quarters of a century ago. Archaeology has come a long way since then, turning from spectacular discoveries to slow-moving teamwork in often far from dramatic sites. However, the complex detective work accomplished by today’s archaeologists, which teases out minor details of the past, has a fascination that rivals Ur’s royal cemetery.

Chapter 1 introduces archaeology and prehistory and describes how the study of the past began and what archaeologists do. The chapter also discusses the importance of archaeology and prehistory in today’s world.

How Archaeology Began

The first archaeologists were adventurers and casual collectors, anxious for fame and fortune or simply looking for new artifacts for their private collections. The practice of aristocratic gentlemen taking grand tours of Mediterranean lands was common as early as the seventeenth century. By the early nineteenth century, many British landowners were trenching into ancient burial mounds for funeral urns and skeletons (see Figure 1.3). They would celebrate their discoveries with fine dinners, toasting their friends with ancient clay vessels.

At the same time, looters and tomb robbers descended on Egypt, seeking mummies, statues, and other precious ancient Egyptian artifacts. Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778–1822), a circus strongman turned treasure hunter, ransacked tombs and temples along the Nile from 1816 to 1819. One of his specialties was collecting mummies. He scrambled into rocky clefts crammed with mummies, “surrounded by bodies, by heaps of mummies in all directions.… The Arabs with the candles or torches in their hands, naked and covered with dust, themselves resembled living mummies” (Belzoni 1820, 157). On one occasion, he sat on a mummy by mistake and sank down in a crushed mass of bones, dried skin, and bandages. Belzoni eventually fled Egypt under threat of death from his competitors. Those were the days when archaeologists settled their differences with guns.

Figure 1.2 A famous ornament from the Royal Cemetery at Ur, called by Leonard Woolley “Ram in the Thicket.” The wood figure was covered with gold leaf and lapis lazuli; the belly was sheathed in silver and the fleece in shell.

The Discovery of Early Civilizations

A couple of centuries ago, you could find an ancient civilization in a month. Englishman Austen Henry Layard and Frenchman Paul-Émile Botta did just that in the 1840s. They dug into vast city mounds at Khorsabad and Nineveh in northern Iraq and unearthed the shadowy Assyrian civilization mentioned in the Old Testament. Layard tunneled into ancient Nineveh, following the walls of palace rooms adorned with magnificent reliefs of conquering armies, a royal lion hunt, and exotic gods. He transported his finds down the Tigris River on wooden rafts supported by inflated goatskins. His excavations also uncovered the royal library of Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (668–627 B.C.), which contained an account of an ancient flood in southern Iraq remarkably like that mentioned in Genesis (see Box 1.1).

Khorsabad, Iraq Palace and capital of Assyrian King Sargon, dating to the eighth century B.C.

Nineveh, Iraq Capital of the Assyrian Empire under King Ashurbanipal, c. 630 B.C.

Figure 1.3 Chaotic excavation. Nineteenth-century diggers uncover a bread oven at Pompeii during the 1880s.

Box 1.1 Discovery

Austen Henry Layard at Nineveh

Austen Henry Layard was the consummate adventurer. He arrived in Mesopotamia in 1840 while traveling from England to India and became obsessed with the ancient city mounds of Nineveh and Nimrud . After a brief and hectic interlude as a diplomat and secret agent, Layard trenched into Nimrud, on the banks of the Tigris River. He unearthed two Assyrian royal palaces in a month and then moved to Nineveh, where he dug hundreds of yards of tunnels deep into King Ashurbanipal’s palace. When his workers uncovered a room full of inscribed clay tablets, Layard casually shoveled them into baskets and shipped them back to London. Layard himself had no idea that this remarkable archive would prove to be the most important of all his discoveries. This was rough-and-ready excavation on a grand scale.

Nimrud, Iraq Capital of Assyrian Kings Esarhaddon (680–669 B.C.) and Ashurbanipal (668–627 B.C.).

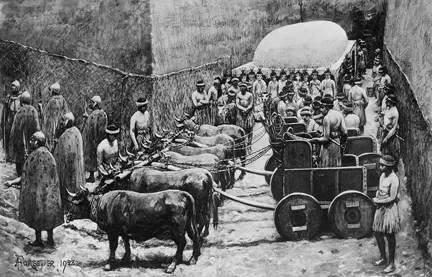

Layard presided over his men like a monarch, throwing feasts, settling quarrels, even performing marriages. He employed hundreds of workers to tunnel into the palaces and to search for spectacular finds, working in temperatures of 45°C (over 110°F). When he found King Sennacherib’s “Palace without Rival,” built about 700 B.C., he uncovered the palace gateway, over 4.2 meters (14 feet) wide, paved with great limestone slabs and guarded by human-headed winged bulls (see Figure 1.4). The huge slabs still bore the ruts of Sennacherib’s chariot wheels.

Layard was an accomplished writer whose best-selling Nineveh and Its Remains (1849) is still in print today. He gave up archaeology in 1852 and became a Member of Parliament and then a diplomat.

Figure 1.4 Englishman Austen Henry Layard supervises the removal of a winged bull from the palace of Assyrian King Sennacherib at Nineveh, in what is now Iraq.

American travel writer John Lloyd Stephens and artist Frederick Catherwood revealed the spectacular Maya civilization of Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras in 1839. They visited Copán , Palenque , Uxmal , and other forgotten ancient cities, captivating an enormous audience with their adventures in the rainforest and with lyrical descriptions and pictures of an ancient society shrouded in tropical vegetation (see Figure 1.5). Stephens laid the foundation for all subsequent research on the ancient Maya civilization by declaring that the cities he visited were built by the ancestors of the modern inhabitants of the region. Like Layard, he was a best-selling author whose books are still in print.

Copán, Guatemala Major Maya center during the mi...