![]()

Part I

Environmental economics

Foundational concepts, theories, and perspectives

THE THREE CHAPTERS that constitute Part I have one thing in common. They all cover concepts, theories, and perspectives that are the foundations for major subjects addressed in environmental economics. The first two chapters examine the economics and ecological perspectives of environmental resources and their implications for the economic and natural world.

Chapter 1 examines what could be considered the mainstream economists’ “pre-analytic” vision of the economy and its relationship with the natural world. What can be observed from the discussion in this chapter is the treatment of the natural environment as one of the many “fungible” assets that can be used to satisfy human needs. In this regard, emphasis is on the general problems of resource scarcity. This being the case, the roles of consumers’ preferences, efficiency, markets, and technology are stressed.

Chapter 2 is intended to provide the reader with the assumptions and theories vital to the understanding of the ecological perspectives of natural resources and the environment—elements crucial to the sustenance of human economy. More specifically, in this chapter economics students are asked to venture beyond the realm of their discipline to study some basic concepts and principles of ecology. The inquiry on this subject is focused and limited in scope. The primary intent is to familiarize students with carefully selected ecological concepts and principles so they will have, at the end, a clear understanding of ecologists’ perspectives on the natural world and its relationship with the human economy. In the final analysis, the major lesson of this chapter is the recognition of biophysical limits that are considered to be relevant to sustainable use of environmental resources.

The last chapter of Part I, Chapter 3, covers two subjects fundamental to environmental economics. First, the basic ecological and technological factors that influence the relationship between economic activity (i.e., production of goods and services) and the waste absorptive capacity of the environment are examined. This effort provides an important initial glance at the ecological and technical determinants of environmental damage function.

The second subject covered in Chapter 3 focuses on the institutional factors that, at the fundamental level, make the allocation and management of environmental resources uniquely problematic. More specifically, attempts are made to delve into the factors that help to explain why a system of resource allocation that is based on and guided by individual self-interest (hence private markets) fails to account for the “external” costs of environmental damage—market failure. It also addresses the difficult choice of institutional arrangements (including government intervention) that are inherent in any effort to correct market failure.

![]()

1

The natural environment and the human economy

The neoclassical economic perspective

Learning objectives

After reading this chapter you will be familiar with the following:

- ▸ The peculiar nature of the standard economics conception of environmental resources as factors of production.

- ▸ How under certain ideal conditions market price(s) may serve as an indicator of

- ▸ “absolute” and “relative” resource scarcity.

- ▸ The extent to which factor substitution and technological change may be used to ameliorate resource scarcity, including environmental resources.

- ▸ A schematic view of a market-oriented economy and how it relates to the “natural” environment in accordance with the neoclassical worldview.

- ▸ The axiomatic assumptions and, at the fundamental level, the analytical principles that are cornerstones of the standard economic conception of the natural environment and its interactions with the human economy.

A VITAL CHAPTER for the understanding of the ideological foundations of the present-day dominant school of economic thought, with respect to the efficacy of the market system to generate reliable indicators of resource scarcity, the bounds of resource substitutability, and the extent to which the human economy is viewed to be dependent on the natural environment; i.e., the concern for general resource scarcity.

∎ 1.1 Introduction

It is safe to say that mainstream economists have a peculiar conception of the natural environment (i.e., all living and non-living things occurring naturally on earth), including how it should be utilized and managed. The primary aim of this chapter is to expose the axiomatic assumptions and, at the fundamental level, the analytical principles that are the cornerstones of the standard economic conception of the natural environment and its interactions with the human economy. This is a crucial issue to address early on because it helps to clearly identify the ideological basis of neoclassical economics, the dominant approach to economic analyses since about the 1870s, as it is applied to the management of the natural environment.

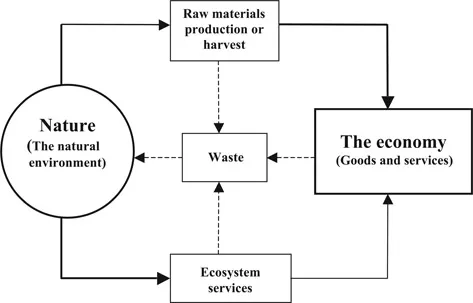

How do neoclassical economists perceive the role the “natural” environment plays in the human economy? For our purpose here, the natural environment could be defined as the physical, chemical, and biological surroundings that humans and other living species depend on as a life support. As shown in Figure 1.1, in specific terms the economy is assumed to depend on the natural environment for three distinctive purposes: (1) raw materials production—which includes the extraction of non-renewable resources (such as iron ore, fossil fuels, etc.) and the harvest of renewable resources (such as timber, fodder, genetic resources, dyes, etc.); (2) the disposal and storage of wastes; and (3) the provision of ecosystem services and amenities such as pollination, habitat and refuge, water supply and regulation, nutrient cycling, climate regulation, aesthetic enjoyments, and so on (Costanza, et al. 2017).

Figure 1.1 A schematic look at how the human economy, for its production of goods and services, depends on the natural environment for raw materials production, disposal of waste, and provision of ecosystem services.

Thus, broadly viewed, the economy is assumed to be completely dependent on the natural environment for raw materials, the disposal and assimilation of waste materials, and for the provision of ecosystem services that are essential for supporting and sustaining life on Planet Earth. Even when they are often accused of taking the services from nature for granted, neoclassical economists are fully aware of the critical significance of ecosystem services to life on earth, including humans. If economists appear to have overlooked or even ignored the contributions of ecosystem services, it is primarily because they have yet to come up with adequate way(s) of imputing the value of the contributions of ecosystem services to the human economy at the margin (ibid).

This much remains indisputable, however. Since the earThis “finite” there exists a theoretical upper limit for resource extraction and harvest and the disposal of waste into the natural environment. Furthermore, nature’s ability to provide ecosystem services is also adversely affected in direct proportion to the amount of resource extractions and harvesting and the disposal or discharge of waste into the natural environment. Thus, as with any other branch of economics, fundamental to the study of environmental economics is the problem of scarcity—the trade-off between economic goods and services and the preservation of the quality of the natural environment. What this suggests is that increased production of goods and services will ultimately have the effect of diminishing the health and/or the productive capacity of the natural environment.

To understand the full implications of trade-offs of this particular nature it will be instructive to have a clear picture of some fundamental (and in some sense axiomatic) assumptions that the standard economics approach uses with respect to the natural environment and how they are related to or influenced by the activities taken within the human economy:

- Environmental resources are “essential” factors of production. A certain minimum amount of these resources is needed to produce goods and services.

- Environmental resources are of economic concern to the extent that they are scarce, and resource scarcity including the environment can be measured (indicated) by market price.

- The scarcity of environmental resources can be augmented either through factor substitutions and/or technological advances.

- Nothing is lost in treating the human economy separate from the natural ecosystems—the physical, chemical, and biological surroundings that humans and other living species depend on as a life support. That is, the natural ecosystem is treated as being outside the human economy and exogenously determined. Note, that to indicate this, in Figure 1.1 the human economy and the natural environment are drawn as two distinctly separate entities. The full extent of the implications of this worldview will be discussed in the next chapter.

From the above discussions it should be evident that, at the fundamental level, central to the neoclassical economics worldview with respect to the “association” of the natural environment and the economic process are the following three key issues: (1) the extent to which market prices adequately signal resource scarcity, including the environment; (2) the extent to which factor substitution and technological advances can be used to augment natural resource scarcity; and (3) the extent to which the human economy can be viewed as an “open system” for both its material and energy use—hence ultimately dependent on nature.

As shown in Figure 1.1, in an open system transformation is characterized by linear processes in which materials and energy enter one part as input or throughput (in this case the human economy) and then leave either as by-product/wastes to the external environment. An open system of this nature can be sustained indefinitely only by a continuous flow of free energy-matter from an external source, in this case nature (more on this later). The rest of this chapter will address these three issues one step at a time.

∎ 1.2 The market as a provider of information on resource scarcity

From the perspective of neoclassical economics, the market system is considered to be the preferred institution for allocating scarce resources. Under certain assumed conditions the market system, guided by the free expression of individual consumer and producer choices, would lead to the maximization of the well-being of the society as a whole—the so-called “invisible hand” theorem (see Appendix A for a formal analysis of this theorem using basic demand and supply analysis). The market system accomplishes this wonderful feat using price as a means of gauging resource scarcity. In this section an attempt will be made to explain, at a very basic level, how market price indicates resource scarcity (Jayasuriya 2015).

Under normal conditions, no payment is made to inhale oxygen from the atmosphere. On the other hand, although less essential than oxygen for our survival, no one would expect to get a membership to a local golf club at no charge (i.e., zero price). Why is this so? The answer to this question is rather straightforward and is explained using Figures 1.2 and 1.3.

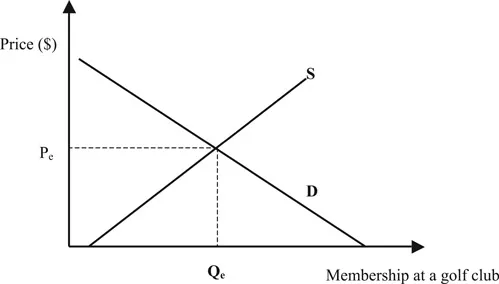

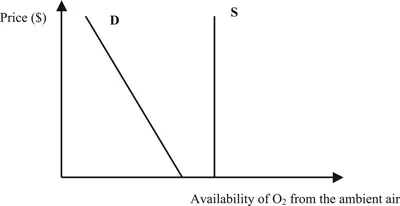

In Figure 1.2 the prevailing market equilibrium (or market clearing) price, Pe, is positive. Hence a unit of this service, membership at a golf club, can be obtained only if one is willing and able to pay the prevailing market price. In other words, this service can be obtained only at a cost (not free). On the other hand, in Figure 1.3, supply exceeds demand everywhere. Under this condition the price for this resource will be zero, hence a free good. This case clearly explains why our normal use of oxygen from the atmosphere is obtained at zero price. Thus, economists formally define a scarce resource as any resource that commands a positive price. In this regard, market price is an indicator of absolute scarcity.

Figure 1.2 Demand and supply and market clearing (equilibrium) price, Pe, for a local golf club membership. The service of a local golf club is scarce because at zero price quantity demanded far exceeds quantity supplied—creating a shortage.

Figure 1.3 Demand and supply of oxygen (O2). O2 is treated as a free good because at zero price quantity supplied exceeds quantity demanded—a surplus.

Therefore, for economists, market is invaluable to the extent that it provides information about the scarcity values of potentially endless numbers of resources at a given moment in time. Based on this market information it is possible to make further insights about resource scarcity. For example, relative (as opposed to absolute) scarcity could be constructed by a ratio of two market-clearing prices.

Suppose there are two resources, gold and crude oil. Let X and Y represent gold and crude oil, respectively. Then Px/Py (the ratio of the market prices of gold to crude oil) would be a measure of relative scarcity. To be more specific, suppose the price for gold is $1,000 per ounce and the price for crude oil is $80 per barrel. In this instance the relative price wo...