Photography

A 21st Century Practice

Mark Chen, Chelsea Shannon

- 682 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

Photography

A 21st Century Practice

Mark Chen, Chelsea Shannon

À propos de ce livre

Finally, here is a photography textbook authored in the 21st century for 21st century audiences.

Photography: A 21st Century Practice speaks to the contemporary student who has come of age in the era of digital photography and social media, where every day we collectively take more than a billion photographs. How do aspiring photographers set themselves apart from the smartphone-toting masses? How can an emerging photographic artist push the medium to new ground?

The answers provided here are innovative, inclusive, and boundary shattering, thanks to the authors' framework of the "4Cs": Craft, Composition, Content and Concept. Each is explored in depth, and packaged into a toolbox the photographic student can immediately put into practice. With a firm base in digital imaging, the authors also shed new light on chemical-based photographic processes and address the ways in which new technology is rapidly expanding photographic possibilities.

In addition, Photography: A 21st Century Practice features:

• 12 case studies from professional practice, featuring established photographic artists and showcasing the techniques, concepts, modes of presentation, and other professional concerns that shape their work.

• Over 40 student assignments that transform theory into hands-on experience.

• 800 full-color images and 200 illustrations, including photographs by some of the world's best-known and most exciting emerging photographic artists, and illustrations that make even complex processes and ideas simple to understand.

• More than 50 guided inquiries into the nature of photographic art to jump start critical thinking and group discussions.

Foire aux questions

Informations

1

Devices

- Camera

- Noun

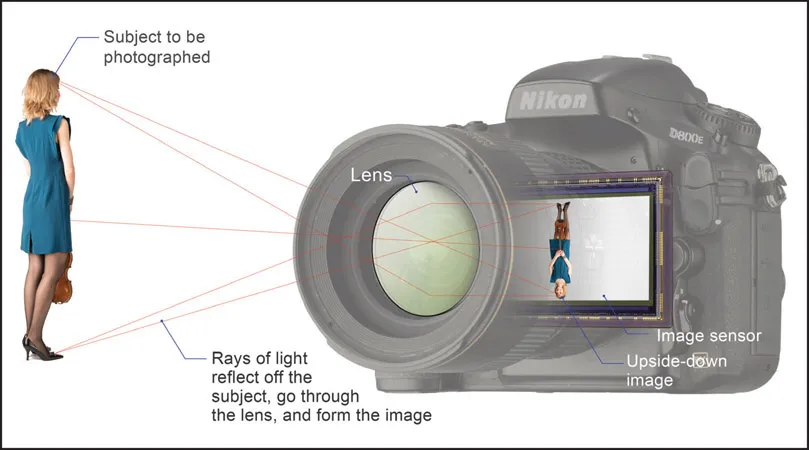

- A device for recording visual images in the form of photographs, film, or video signals.

- The ability for the user to take as much or as little control as they wish

- Good optical quality, meaning that the camera is capable of producing sharp images with minimal aberration (see Chapter 2: Optics for more on this)

- The capability to change focal lengths with a zoom lens and/or with interchangeable lenses

- The ability to deliver RAW image files (in the case of digital cameras; see Chapter 3: Exposure for more on RAW files)

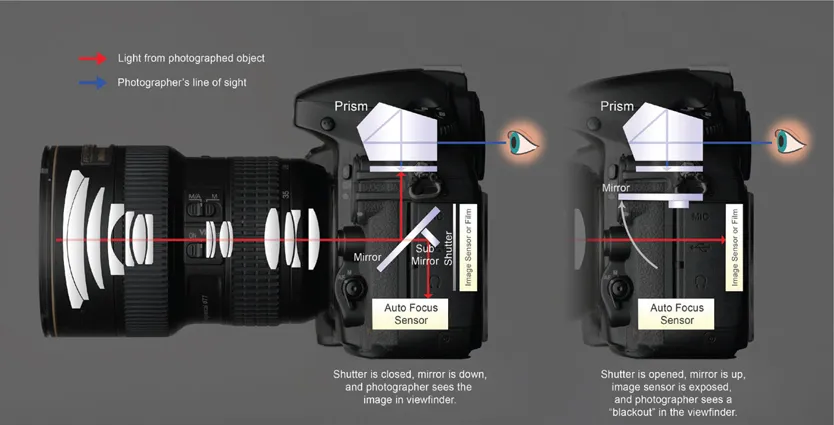

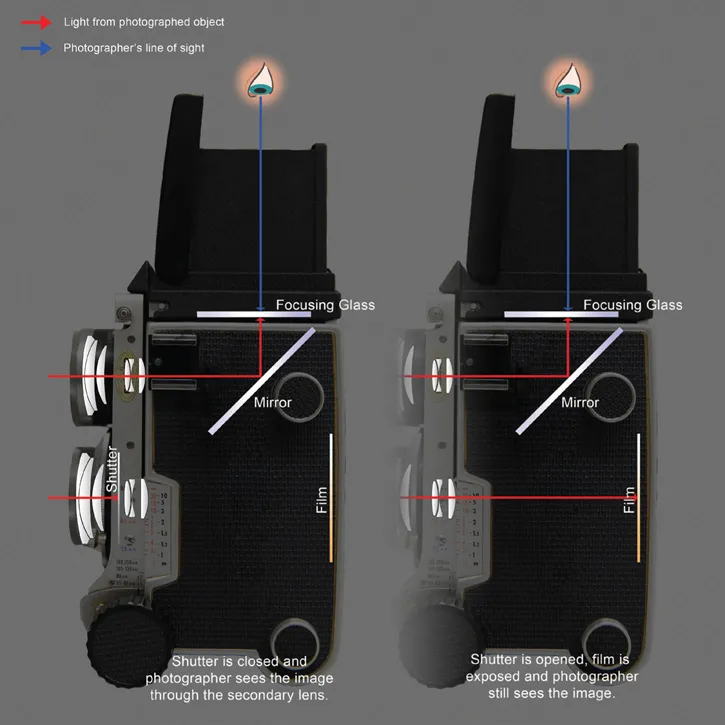

SLR cameras