![]()

Part I

The ancient Near East

![]()

Chapter 1

The origins of the civilisations of Egypt and Mesopotamia

On the banks of the rivers Euphrates and Tigris in Mesopotamia (largely what is now Iraq) and the Nile in Egypt emerged civilisations that were to have a profound influence on the history of the eastern half of the Mediterranean. The rise of these civilisations, just before 3000 bc, was characterised by increasing urbanisation, the birth of states and the invention of writing. These civilisations did not appear out of the blue of course; their foundations had been laid over a period that spanned several hundreds of thousands of years. Archaeologists have divided this long period, which is called the Stone Age, into an Old, Middle and New Stone Age on the basis of changes in the stone implements that were produced during that period. In the Old and Middle Stone Ages people lived off what they happened to come across, off the animals they hunted and the plants they gathered. They followed their prey into new areas and were hence constantly on the move. By the end of the Middle Stone Age (c. 10,000 bc), man had improved his tools to such an extent that he was able to make more efficient use of natural resources. That meant that some groups of people could remain in one area for a longer period of time, sheltered from the elements in primitive huts or caves. The next step in man’s development was the transition to an entirely new way of life, characterised by a greater control of nature: man started to cultivate the cereals which he had until then always gathered as wild plants, and domesticated the animals which he had hunted in the past. This transition took place at different times in different parts in the world, but it is believed that it occurred in the Near East first. The process really got under way around the beginning of the New Stone Age, or Neolithic, as this period, characterised by the use of ground stone tools, is also called. Being of such tremendous importance for the further development of civilisation, this transformation is often referred to as the ‘Neolithic revolution’, although the whole process actually took thousands of years and the first signs of the fundamental changes that were to take place had already appeared long before the Neolithic.

Two different kinds of agriculture are distinguished: rainfall agriculture and irrigation agriculture. A prerequisite for rainfall agriculture is an annual precipitation of at least 250 mm (See map 1.1). So this form of agriculture could be practised only in Iran, northern Iraq, northern Syria and the coastal Mediterranean. Egypt and southern Mesopotamia had to rely on irrigation agriculture. Areas in the Near East that receive an average of 250–400 mm per year and are dependent on rainfall agriculture are very vulnerable. A slight decrease in rainfall will immediately lead to a food crisis and a more protracted change in climate will have major social and political consequences.

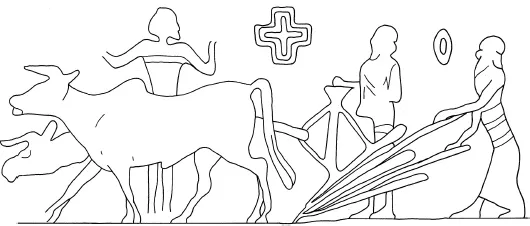

‘Irrigation’ is understood to include both natural and artificial irrigation. The best conditions for agriculture based on natural irrigation were to be found in Egypt. Every year, the Nile flooded the land before the sowing season (between July and September). The Egyptians could then sow their crops in the damp soil when the river receded. In Mesopotamia the land was less regularly flooded, the floods moreover occurring earlier in the year – from February until April – namely just before harvesting time. This meant that the occupants of that region had to practise artificial irrigation. Irrigation agriculture was far more productive than rainfall agriculture, enabling crop yield ratios of at least 15:1, often indeed a lot higher. We get a good impression of how high such ratios are when we compare them with later figures for Greece, Italy and medieval Europe, where the average ratio was about 4/5:1 and a good ratio was 7/10:1 (e.g. in Campania in Italy). Another reason why crop yields were higher in Mesopotamia is that people in that area used a sowing plough (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Sowing plough. Impression of a cylinder seal (second millennium).

The development of agriculture was of fundamental importance for the further history of mankind. It meant that more people could remain settled in one particular area for a longer period of time and that more people could concentrate their attention on activities other than food production. People consequently started to specialise in all kinds of crafts and became carpenters, tanners, scribes (at least after the invention of the art of writing, around 3400 bc) and metalworkers (after around 3000 bc, when man discovered how to exploit and smelt copper ore and produce bronze, an alloy of copper and tin). A civil service and a priesthood emerged (and the associated institutions: the state and the temple). Some of the villages that had originated at the beginning of the Neolithic began to resemble fortified cities; Jericho for example had already evolved into a city around 7000 bc and there were several cities in Asia Minor and Syria. The largest and most influential cities, however, were those that arose on the banks of the major rivers of Egypt and Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium bc. It was there, along those rivers, that the largest quantities of food could be produced and the largest numbers of people could live together.

The core of a Mesopotamian city was the temple, the abode of the state deity, whose needs had to be provided for by the community. Those temples grew into powerful organisations that owned vast estates; they engaged in a wide range of activities, including agriculture, stock breeding and various crafts, for which they employed a large staff.

Figure 1.2 Clay tablet from Jebel Aruda, Syria, length 9.2 cm, c. 3400–3200 bc, in the collection of the Aleppo Museum.

It was the requirements of this temple economy that led to the invention of writing, sometime between 3400 and 3200 bc. The Mesopotamian script is known as the ‘cuneiform’ script – so called after the wedge-shaped appearance of the impressions of which the later characters of that script were composed. The hieroglyphic script of the Egyptians was developed around the same time as the cuneiform script.

At first, the cuneiform and hieroglyphic scripts were both partly pictographic (with each word being represented by a picture) and partly ideographic (with each word being represented by a symbol). Later on, the signs came to stand for sounds (syllables), too. The Egyptian script rendered only consonants, vowels being ignored. Both the Mesopotamian and the Egyptian scripts remained highly complex forms of writing and were used only by small groups of specially trained professional scribes.

In antiquity, the presence of cities did not lead to contrasts between the urban and rural populations of the kind known to us from later times. In most of the cities the majority of the inhabitants were peasants, who left the city to work on their land every morning and returned in the evening. In the ancient Near East, a far greater and far more important contrast than that between city dwellers and country folk was that between the sedentary and the nomadic way of life. This contrast was closely associated with a major difference in subsistence patterns. Agriculturalists led a sedentary life; they remained settled in one area because they had to till their land and look after their crops. Herders were nomads; they constantly moved around from one place to another, in search of fresh pastures for their animals. However, there was not always such a clear-cut difference between the two. Primitive agriculturalists sometimes remained in one area for only a short period of time, to then move on again a few years later, when they had exhausted the soil. Some herders moved around within a relatively small area – for example from summer pastures to winter pastures. This seasonal migration is called ‘transhumance’. The transhumant nomads liked to remain in the vicinity of the settlements of the agriculturalists, with whom they could then exchange products. Occasionally a group of (semi)nomads would adopt a partly or entirely sedentary way of life and take control of a city. There were also wealthy landowners who owned herds besides land and employed herders to pasture their animals, sometimes at considerable distances from their dwellings. Throughout the entire history of the ancient Near East the representatives of these two opposed ways of life had an ambivalent relation towards one another, because the sedentary peoples were afraid of being plundered by the (semi)nomads and the two groups were dependent on one another for the exchange of products. The contrast between the two different ways of life became a popular theme in the literature of this area. It forms the basis of the biblical story of the shepherd Abel, who was murdered by the agriculturalist Cain.

The geographical conditions of Egypt and Mesopotamia were very similar in some respects: both areas were dependent on river water due to the almost total absence of rain, and both were poor in various important resources, such as metals and timber. In other respects, however, they were totally different. Conditions for agriculture for example were more favourable in Egypt than in Mesopotamia. As already mentioned, the Nile flooded the land from mid-July to mid-November – that is before the sowing season – and the Euphrates and Tigris not until later in the agricultural year (March to May) – that is just before the harvest. Whereas the Egyptians could sow their crops in the fertile deposits left behind by the receding river, the Mesopotamians had to go to great efforts to conduct the water to their fields via canals. The water of the Nile was moreover of a better quality; that of the Euphrates and the Tigris contained harmful salts, which became mixed with the groundwater. The groundwater level of the low-lying, flat land was very high and the salts migrated to the surface of the land via capillary cracks in the clay. Protracted irrigation without sufficient drainage could ultimately make the soil unfit for cultivation owing to complete salinisation. That this indeed happened can be inferred from the crops that were cultivated: in southern Mesopota...