![]()

CHAPTER 1

Leo Boer, a Dutch Student in the Near East (1953–1954)

Bart Wagemakers

Before focussing on several archaeological sites in Israel and the Palestinian territories dealt with in the succeeding chapters, it is worth taking a closer look at the background of Leo Boer himself and at the documentation of his activities in 1953–1954, which is the starting-point of this book. This chapter contains a biography on Boer, an account of his stay in Jerusalem in the mid-1950s, an overview of his photo collection and travel account, and ends by showing the significance of his documentation.

Leonardus Hermanus Cornelis (Leo) Boer (1926–2009)

Leo Boer was born in the city of Delft in the Netherlands on 23 July 1926. He grew up in a Catholic family and he had already decided, when he was quite young, to devote his life to religion. After having attended religious education colleges in Sint-Oedenrode (1938–1943) and Simpelveld (1943–1944), Boer started work as a novice, under the priest name of Barnabas, in Bavel on 31 August 1944. On 25 September 1945 he took his ‘temporary vows’ and became a member of the Congregazione dei Sacri Cuori di Gesù e di Maria (SS.CC. Picpus; Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary). From 1945 till 1947 he studied philosophy at the Major Seminary in Valkenburg (in the south of the Netherlands. After completing this study, he went to Rome to study Theology at the Pontificia Università Gregoriana (Pontifical Gregorian University). Having graduated in 1951, he then became a Candidato al Dottorato at the Pontificio Instituto Biblico (Pontifical Biblical Institute), which is located across the square from the Gregorian University. Four years later Boer completed his studies by writing his exercitatio ad lauream, about the ‘The Sanctuary of Bethel in the Books of Judges and Samuel’.

It appears that Boer was a brilliant student. He graduated magna cum laude from the Gregorian University and his study results at the Biblical Institute were also on average above a 9 (on a scale to ten). For his exercitatio he even gained a 9.75. Hence, it is no wonder that the Biblical Institute awarded him his degree maxima cum laude.

In 1953, while he was working on his PhD at the Biblical Institute, the 26-year-old Boer was given the opportunity to study at the renowned École Biblique et Archéologique Française de Jérusalem for one year (Figs 1.1 and 1.2). There he chose to read ‘Biblical study’, instead of ‘Archaeology’, the other field of study available at this institute. This choice tended to determine the subjects which Boer studied, as the register of the École Biblique in 1953–1954 shows: ‘Rev. Pat. Leonardus BOER, Congreg. Sacrorum Cordium (Picpus), Hollandus, S. Theol. Licens., S.S. Prolyta, Exeg. V.T.; Exeg. N.T.; Hist. Bibl.; Archaeologiae; linguarum agyptiacae et arabicae studens (cursus maior) nec non syriacae’. Although Boer preferred biblical study to the field of archaeology, he was to encounter the archaeology of the Holy Land in several ways during his stay at the École Biblique.

Figure 1.1: Leo Boer, aged 26, posing in the Jordan desert (19 October 1953).

Figure 1.2: Photograph of the École Biblique, taken from the Ben Shadad road (6 December 1953).

After his year in Jerusalem Boer returned to Rome and wrote his exercitatio ad lauream. Shortly after that, in 1955, he moved back to the Netherlands where he held several offices in the church. Then on 28 July 1955 Boer was appointed professor in the Holy Scripture at the Major Seminary in Valkenburg, where he had been a philosophy student almost a decade earlier. His main teachings concerned the exegesis of the Bible and contained courses such as ‘Luke 1 and 2’, ‘The travel accounts of John’ and ‘An introduction to the letters of Paul’.

Out of the blue, or so it seemed to people around him, his liturgical career came to an abrupt end in 1968. In November 1967 Boer applied for priestly dispensation, which was granted to him on 25 October 1968. His motives for applying become clear in a letter to his colleagues in June 1968:

‘In November of last year, I applied for priestly dispensation. I have decided to do this, because for me the meaning of the priesthood has almost faded away in the way my life has changed. And I did not want to appear as someone who I am not anymore in my heart. Besides, I found my thoughts and myself to be no longer compatible with the existing notions and with the meaning of the office. I have no intention of leaving the church and I hope to give shape to the Gospel – which has been such an important part of my life because of my study – in a new way. Whether I will ever get married, I don’t know. At the moment I have nobody in mind.’

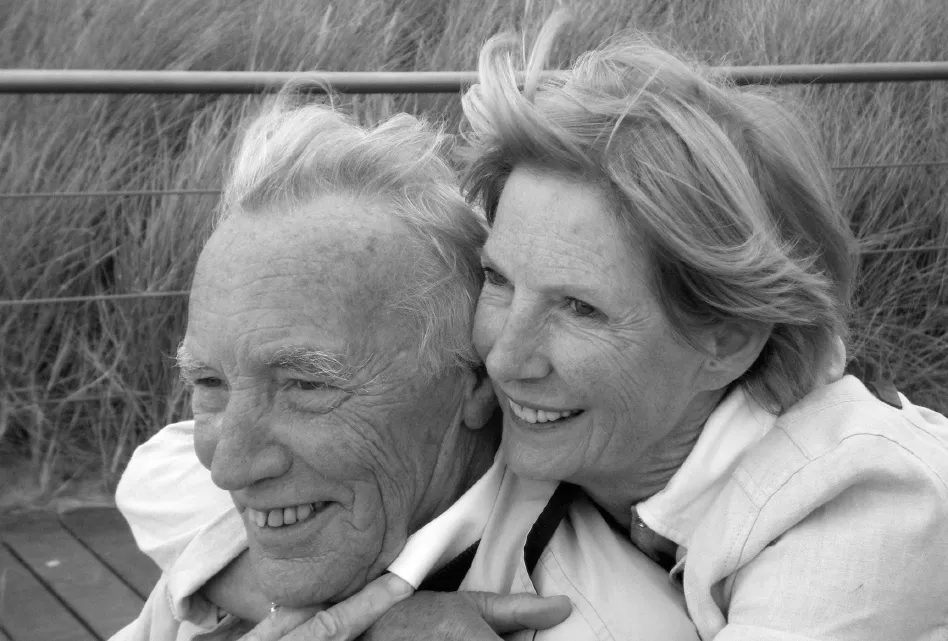

After he was granted priestly dispensation, Boer’s life changed completely, albeit gradually. He married Annemie Hakze in 1970 and they raised five boys (Fig. 1.3). He found work in the building trade, yet he never lost his interest in theology. Up until his death on 9 November 2009 he continued to give many lectures about topics relating to religion. Apart from giving lectures, he also worked as a volunteer for several charities.

Figure 1.3: Leo and Annemie Boer (August 2008).

Boer was an extremely kind person who was concerned about the needs of others. His social skills did not remain unnoticed while he was a lecturer at the Valkenburg seminary. Jan Wouters, one of Boer’s former students, remembers Boer, besides lecturing on the Holy Scriptures, organising several film evenings for the students every year and arranging the annual carnival festivities at the seminary in the 1960s.

Not only former students remember Boer kindly. Also the people who got to know Boer in Jerusalem, were impressed by his cheerful character. One of those people was Th. C. Vriezen (1899–1981), Old Testament professor at Utrecht University, who travelled frequently to the Levant in the first half of the twentieth century. When Vriezen visited Jerusalem in the spring of 1954, he met with Boer several times; they had lunches and dinners together and they joined the same daytrip to the monastery of Latrun. In his letters to his family in the Netherlands, Vriezen mentions Boer several times as the ‘cheerful Father Boer’. This jolly disposition of Boer was even the reason for Vriezen to place a bet. A letter he wrote to his wife on 29 June 1954 reads:

‘.... I must rectify my previous statements a bit; I have always been in the opinion that Father Boer, the cheerful Father, was a Jesuit; but now I have been told that he is not. He belongs to the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary and somebody here (an Englishman who previously lived in a Catholic institute in Paris) said: “a Jesuit never smiles, and merely chuckles when he laughs, but this Father roars with laughter, so he could not be a Jesuit” (which was confirmed by two other Fathers here). Therefore, if you ever happen to meet the laughing Father, he is not a Jesuit as I wrongly assumed. It cost me two packets of cigarettes, because the Englishman wanted to bet...’1

Besides his cheery character, Boer was always meticulous and well-organised. An example: although he never developed the photographs he took during his stay in the Near East, he made a minutely detailed list of them including the numbers of the pictures, captions and the dates when they were taken. Moreover, in his travel account, Boer refers to the numbers of the corresponding photographs. Thanks to this list, it was possible to identify the names and locations of the places shown in the pictures.

Another example of his tremendous sense of organisation is the way in which he ordered his own office and study. Even after his death I was able to find all the documentation about his travels in the Near East without any difficulty: notebooks; maps; curriculum and code of conduct of the École Biblique; even a drawing of the routes of the four trips he made with his lecturers and fellow students at Petra.

One further aspect of his character I should like to mention here, namely his excellent memory. Every bit of information about his time in Jerusalem which he told me during the many conversations we had, and which I was able to check, appears to be correct. The following example is a perfect illustration of this. One day Boer mentioned to me that, on the last day of his stay during the third archaeological expedition of Father Roland de Vaux in Khirbet Qumran, on 27 March 1954, they found an artefact which was identified by someone as an inkwell. A few hours later Boer returned to the École Biblique and never heard of this ‘inkwell’ again. Oddly enough, the field notes of de Vaux do not mention any inkwell found in situ in 1954 (Humbert and Chambon 2003). Having searched in the field notes myself for a mention of an artefact that was found on 27 March and which could have been wrongly identified as an inkwell – possibly by one of the assistants or students present at the site – I came to the conclusion that there could only be one solution: on the day concerned the team excavated an unguentarium (archive number: 1500) at locus 96, a small flask used for preserving perfume, essential oils or other precious liquids.2

To try and find out whether what Boer had seen was indeed this same flask, I compared the available data in the archives of the École Biblique with the details Boer had given me of the object that was found in his presence 55 years ago. The resemblance of the data was astonishing! According to Boer, the ‘earthenware artefact had the same colouring as the wall where it was found (a kind of yellow), had a length of approximately ten centimetres and the thickness of the rim was five millimetres’. The unguentarium that is stored at the École Biblique is also made of pottery, its length is 10.6 centimetres and the rim five millimetres in thickness. Even the colour mentioned on the data card of the flask corresponds with Boer’s description: ‘terre chamois’ (Wagemakers 2009). These details of the flask have never been published before, and this story demonstrates how excellent Boer’s memory was.

Following this brief biography on Leo Boer, it is important now to describe the new environment he entered into in October 1953, including the political situation of Jerusalem and daily life at the École Biblique in the 1950s, so as to have a proper understanding of his travel account and insight into the photographic material.

Israel, Jordan and Jerusalem in the 1950s

Boer visited the Near East in turbulent times: the Second World War ended nearly ten years earlier, yet the foundation of the State of Israel and the subsequent War of Independence took place only five years prior to Boer’s arrival in East Jerusalem on 14 October 1953. During the years 1953–1954 this region was not at all peaceful and Boer’s account gives several references to the tense political situation, including indications of anti-semitism during his journey from Rome to East Jerusalem. The first anti-semitic incident concerned a fellow passenger on the boat from Naples to Beirut – a Muslim from Cairo – who Boer visited because the man was ill. Boer writes that the man ‘had been under the weather much in his lifetime, because his wife was a Jewess’. Further on, when Boer records his journey from Baalbek to Damascus, he writes: ‘Useless formalities at the border. Everything went well. Hatred against Jews’.

The creation of new borders and the tense political situation since 1948 forced the Jordanians to move existing roads. For example, the road to Bethlehem and Hebron, which started at the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem, ran through Israeli territory. For that reason the Jordanians decided to build a new road in 1952.3

On several occasions, the group from the École Biblique encountered a hostile, ‘anti-Western’ attitude from local residents. At times, this tension led to the cancellation of an intended visit to a site or village, such as the planned visit to Halhul (Alula), located in the neighbourhood of Hebron. At other times, the group did manage to visit a site as intended, but only in the company of armed policemen or soldiers, such as happened in Lachish. Another good example of this is their visit to the city of Hebron. Boer writes that, before entering the city, a policeman got onto the bus as a precaution. According to Boer, the inhabitants would sometimes be aggressive towards Westerners, and the group was strictly forbidden to take photographs of local residents. In addition, during an excursion in the Negev, the group was accompanied by an armed escort, although Boer does not mention whether this was for the same reason as the cases above refer to. During their visit to the caves of Marissa, near Beth Govrin in Israel, the same armed escort asked the party to leave the area immediately after shots were heard at close range.

This strained atmosphere was also present in Jerusalem. Between 1948 and 1967 the city was divided into an Israeli (West) and a Jordan section (East). The École Biblique was located in East Jerusalem and was separated from the Jewish section by a length of no man’s land. The crossing-point was situated at the so-called Mandelbaum Gate (Fig. 1.4), about 150 metres to the north of the institute. Travelling from one section to the other required certain formalities, such as being in possession of two passports because it wa...