![]()

PART I

DEJ

![]()

Chapter 1

Lufthansa

I’m traveling light as I step aboard the Lufthansa 747 jumbo jet at Los Angeles International Airport’s Bradley Terminal. It’s Friday evening, the start of the Labor Day holiday weekend, but I’m not going on vacation and I won’t be gone long, so I don’t need much. I’m on my way to northern Austria to walk the grounds of the concentration camps where the Nazis tortured and enslaved my father, and to find precisely where he hid after he’d escaped. It is a journey that beckoned to me from the moment my cousin Vivian telephoned from Israel a few years earlier with astonishing news about him.

In June 1944 my father entered KZ Mauthausen as a 160-pound, eighteen-year-old youth.1 By the Nazi’s own rating system, KZ Mauthausen and its nearby sub-camp, KZ Gusen I, were the harshest, cruelest labor concentration camps in the entire Third Reich. After ten brutal months in both camps, my father had been whittled down to 80 pounds. And then, because he was still alive five weeks before the war ended, he was forced onto a Nazi death march with the expectation that he would finally collapse and die somewhere on the road between KZ Mauthausen and KZ Gunskirchen, a concentration camp thirty-four unfathomable miles away.

My father came close to dying many times that year, but he didn’t die in those concentration camps, and he didn’t die on that death march. Nor did he die on a second death march ten days later.

Instead, he escaped from the death marches. Twice. Once was unheard of. Twice was thought to be impossible.

![]()

Chapter 2

Cousin Vivi

Early on a warm May morning in 2007, I was sitting at my desk in a Los Angeles office high-rise, facing computer screens showing stock and bond prices and world news, talking heads chirping away on the wall-mounted television, volume set on low. I work in the financial field and was just beginning my day. The rising sun threw long shadows off the tall buildings visible from my window.

As I was reading the morning’s headlines, my cell phone rang. Caller ID revealed it was my cousin Vivian Tobias, my father’s sister’s daughter. She’s my age, forty-eight at the time, and lives in Netanya, Israel, a pleasant coastal resort town twenty miles north of Tel Aviv, with her husband David. Though it was already mid-afternoon in Israel, she usually didn’t call me this early. I answered my phone.

Normally we would begin by comparing notes on our children, my three teenagers and her two boys who were doing their compulsory Israeli Army service. Not this time. Vivi, as I called her, got right to the point.

‘I was on the computer looking for something for my mother, and I saw your father’s picture,’ she said in her melodious voice. She had learned English in Israeli schools. ‘Did you know he’s on the internet?’

‘My dad?’ I asked incredulously. ‘No, I had no idea. Where did you see him?’ Why, I wondered, would he be on the internet six years after his death? Maybe she’d made a mistake.

‘He is on the Mauthausen Concentration Camp website,’ Vivi replied. ‘It says he escaped from a death march.’

‘It’s true, he did,’ I confirmed. I had no idea Mauthausen even had a website. I’d never bothered looking.

‘Jackie,’ she said, addressing me by the childhood name my relatives still use, ‘you make it sound like it’s nothing, but it seems your father is special. I’ve read about the death marches. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were forced to march thirty, forty, even one hundred miles to get away from the Russians and Americans who were coming near to their concentration camps. Almost no one escaped from the marches. But your father did.’

‘Well, he actually escaped twice,’ I said. ‘He told me the story many times over the years.’ I stole a peek at my computer screens.

‘I think you don’t understand.’ Now I heard a distinct note of irritation in her voice. ‘His is the only story on the Mauthausen website about escaping from the death march. No one else is there, only your father. I don’t think you know the whole story. Please, type Mauthausen and his name into Google. You will see.’

I did as she said, and my father’s name appeared atop a full screen of search results.

‘Huh, I had no idea,’ I said, more to myself than to Vivi.

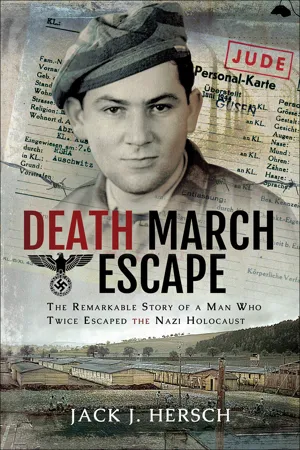

Clicking on the first link took me to KZ Mauthausen’s website. I was instantly drawn to my father’s name in the menu on the top of the webpage, in a section called Death Marches. Sitting straighter in my chair, I clicked on it, and after a beat, a black-and-white picture unfurled onto my screen. It was a head shot, a brilliantly clear photo from the shoulders up.

A young man who looked remarkably like my seventeen-year-old son, Sam, was staring at me. I stared back, frozen.

It was my father, as a teenager.

I had never before seen this photo, or any like it, of my father in his youth. I kept all my parents’ old photographs. I had only a few of my father from before the war, and all were taken at a distance. None let me see so clearly the angular planes of his young face, and the impish eyes that belied a man with a monumental determination to survive. My father told me that before being sent to a concentration camp he had done modeling work for his town’s photographer. The professional-looking head shot now on my screen must have been one of those pictures. His hair was wavy and thick. He was wearing a light colored, pin-striped, open collared shirt and a stylish, peak-lapel blazer. He looked like he was about to tell one of his unlimited supply of jokes.

How had the people at the Mauthausen website gotten this photo?

I noticed the English caption underneath. I read it aloud:

In April 1945 Ignaz and Barbara Friedmann from Enns Kristein rescued the completely exhausted David Hersch from the death march from Mauthausen and Gunskirchen and hid him until the end of the war.

I knew about the Friedmanns. I knew the story of how they’d found my father the day after his second escape and had hidden him, at great risk to themselves, until American soldiers liberated Enns, their town. How did the Mauthausen website people know his story? Why had they singled him out? Why was his story the only one here?

My world had gone silent.

I had often heard and read that survivors of the ‘Holocaust,’ Hitler’s nearly successful attempt to destroy the Jews of Europe, are reticent about recounting their experiences in ‘the camps’ (survivors, I knew from growing up with many of them, referred to concentration camps as, ‘the camps’).1 Supposedly many survivors have gone their entire lives without breathing a word of what they’d endured. I had even heard many of them had not cracked a smile or told a joke since the day they were crammed aboard a cattle car bound for places like Auschwitz and Treblinka.

My father was nothing like those survivors. He told me often about his time under Nazi occupation in Hungary, his year in the camps, and his escapes. He told his story lightly, almost breezily, and without hesitation.

He particularly liked to tell his survival story on Passover. After all, the holiday commemorates the Jews’ breakout in the dead of night from Egyptian bondage under the command of Moses and presumably with supernatural help. The first night of Passover is marked by a traditional family meal, the Seder, where it is customary to recount that ancient midnight adventure. Since the Passover meal is, at its core, a celebration of escape and deliverance, at every Seder my father recounted to my brother and me his own adventures of escape, capture, near-death, and escape again.

As readily as my father told his tale, I sensed a hidden darkness within him, pain he never shared with me. The only hints he ever gave of it was when he’d tell me he hadn’t slept well, or he’d had a nightmare about the camps. But then he would quickly toss it off with a casual wave of his hand, saying it was, ‘no big deal,’ just an off night.

‘You have this picture, yes?’ Vivi snapped me back to the present.

I took a deep breath. ‘No,’ I confessed, ‘I don’t. Does your mother?’

Vivi’s mother, Rosie, and my father were two of eight children in their family. Four of them – my father, Rosie, and two uncles – had survived the Holocaust. The other four had been murdered by the Nazis.

‘No, but she remembers it. She said it was taken when your father was seventeen. A local photographer used it as an advertisement for his studio.’

As I’d suspected. ‘Interesting,’ I said. ‘But I can’t imagine how the people at Mauthausen got it.’

‘Do you think maybe he gave the picture to them when he visited to there?’

‘What?’ Now alarm bells rang in my head. ‘My dad never visited Mauthausen,’ I said firmly. ‘He never went back there, he hated that place. He nearly died there.’

‘Yes, he did,’ Vivi replied with absolute conviction. ‘He went back in 1997. He told this to my mother. He didn’t tell you?’

I was utterly stunned. Until that moment I believed my father had told me everything going on in his life. ‘No,’ I managed to say. ‘No, he didn’t. Are you sure he went back?’

‘Yes, one hundred percent I am sure. I asked my mother again just today, and she said he went alone, on his way to Israel.’

Vivi’s mother and the two other surviving Hersch brothers all lived near each other in Natanya. My father had lived in Long Beach, New York, and visited his sister and brothers at least twice a year. I always knew when, and where, he was going. Or so I thought.

Vivi continued, ‘My mother asked him about it when he came to her house and he told her he went, but he said that it was no big deal. He didn’t say anything more about it.’ ‘No big deal’ was one of my father’s favorite phrases. I easily imagined him saying that to his sister.

‘This makes no sense,’ I said. ‘I just can’t understand why he didn’t tell me.’

‘I’m sure he had a very good reason,’ Vivi said definitively. ‘I think you should try to find out what his reason was. I would want to know if I were you.’

Vivi and I sent our love to each other’s families and hung up, leaving me alone with the photo of my father filling my computer screen while the rising sun’s rays streamed through my office window.

![]()

Chapter 3

Dad

David Arieh Hersch, my father, was 5ft 10in tall, and slim but deceptively strong. He wore his salt-and-pepper hair combed back, had a fantastic smile that lit up his face, and owned a thin line of a scar under his left eye from a seltzer bottle that had exploded in his hands. After the war he’d worked for a short while in a seltzer bottling plant in Haifa, Israel, owned by his girlfriend’s father (she was not my mother, Mom hadn’t come along yet).

My father was a fun, light-hearted guy who laughed easily, spoke nine languages fluently, followed the New York Jets football team closely, loved reading non-fiction, and had a twinkle in his eye. It was in his left eye, and when he told you a story I swear it sparkled. He remembered jokes and told them like a stand-up comic, in any of his languages. When he told them, he had a knack of bursting out laughing just as he delivered the punch line, and that always brought you right into the joke with him.

He was born on July 13, 1925, in the semi-rural town of Dej, Romania (‘Dej’ rhymes with ‘beige’). In the years before World War II, Dej was a community of 15,000 in the Transylvania region, thirty-seven miles north of Cluj, Romania’s second biggest city.

Transylvania is home to verdant hills, shimmering farm fields, and salt, gold, copper and iron mines. Its mountains are also the home of Count Dracula, if you believe in those things. The Austro-Hungarian Empire controlled the region from the mid-1800s until its defeat in World War I, when the empire was broken apart. The Kingdom of Hungary and the Austrian Republic became distinct sovereign nations, while Transylvania was cleaved off and given to Romania.

Typical of communities in the region, the Dej my father knew was populated by farmers, merchants, professionals, and tradesmen. The homes on its rolling hills were of sturdy cement construction, painted white or in light pastels of tan, green and blue, with red tile roofs and tidy back yards. Like other European towns as old as Dej, its streets were narrow, serpentine, and mostly unpaved, running haphazardly out from the main town square, which was then (and is still today) dominated by a sixteenth-century Calvinist church boasting a 230ft tall spire. Horse-drawn-cart was the dominant means of transportation in my father’s time, and even now horses can be heard clopping around the town.

My grandfather, Jozsefne Jacob, was born in Dej in 1886. In the Jewish tradition of naming children after deceased relatives, I’m named after him, though I’ve been given the inverse of his name, and thankfully a few letters were left off, so legally I’m Jacob Josef. Everyone now calls me Jack, but growing up I was Jackie because my mother liked the name.

My grandfather was of average height and thin, with a tightly trimmed beard and innate but unexploited talent as a writer and artist, but he made his living as the owner of a small soap factory. In 1908 he married my grandmother, Malvina, who was five years younger, a sweet and charitable woman who was better known by her Hebrew name, Malka.

The eight Hersch siblings were born in two bunches. Two girls and two boys arrived before my grandf...