![]()

Chapter One

Introduction to Options

What Is an Option?

Options are simply legally binding agreements – contracts – between two people to buy and sell stock at a fixed price over a given time period.

There are two types of options: calls and puts. A call option gives the owner the right, not the obligation, to buy stock at a specific price over a given period of time. In other words, it gives you the right to “call” the stock away from another person. A put option, on the other hand, gives the owner the right, not the obligation, to sell stock at a specific price through an expiration date. It gives you the right to “put” the stock back to the owner. Option buyers have rights to either buy stock (with a call) or sell stock (with a put). That means it is the owner’s choice, or option, to do so, and that’s where these assets get their name.

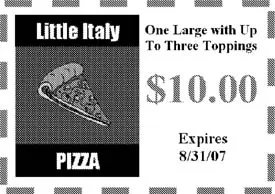

Now you’re probably thinking that this is sounding complicated already. But options are used under different names every day by different industries. For instance, we are willing to bet that you’ve used something very similar to a call option before. Take a look at the following coupon:

The way pizza coupons and call options work is very similar. This pizza coupon gives the holder the right to buy one pizza. It is not an obligation. If you are in possession of this coupon, you are not required to use it. It only represents a right to buy. There is also a fixed price of $10.00. No matter how high the price of pizzas may rise, your purchase price is locked at $10.00 if you should decide to use it. Last, there is a fixed time period, or expiration date, for which the coupon is good.

Now let’s go back to our definition of a call option and recall that it represents:

1) Right to buy stock

2) At a fixed price

3) Over a given time period

You can see the similarities between a call option and pizza coupon. If you understand how a simple pizza coupon works, you can understand how call options work.

Now let’s take a look at a put option from a different perspective. Put options can be thought of as an insurance policy. Think about your car insurance, for example. When you buy an auto insurance policy, you really hope that you will not wreck your car and that the policy will “expire worthless.” However, if you should total your car, you can always “put” it back to the insurance company in exchange for cash. Put options allow the holder to “put” stock back (sell it) to someone else in exchange for cash. Remember, if you buy a put option, you have the:

1) Right to sell stock

2) At a fixed price

3) Over a given time period

As you will discover, the mechanics of calls and puts are exactly the same; they just work in the opposite direction. If you buy a call, you have the right to buy stock. If you buy a put, you have the right to sell stock.

Option Sellers

We know that buyers of options have rights to either buy or sell. What about sellers? Option sellers have obligations. If you sell an option, it is also called “writing” the option, which is much like insurance companies “write” policies. Buyers have rights; sellers have obligations. Sellers have an obligation to fulfill the contract if the buyer decides to use their option. It may sound like option buyers get the better end of the deal since they are the ones who decide whether or not to use the contract. It’s true that option buyers have a valuable right to choose whether to buy or sell, but they must pay for that right. So while sellers incur obligations, they do get paid for their responsibility since nobody will accept an obligation for nothing.

There are some traders who will tell you to always be the buyer of options while others will tell you that you’re better off being the seller. Hopefully, you already see that neither statement can always be true, because there are pros and cons to either side. Buyers get the benefit of “calling the shots,” but the drawback is they must pay for that benefit. Sellers get the benefit of collecting cash but they have a drawback in that there are potential obligations to meet. What are the sellers’ obligations? That’s easy to figure out once you understand the rights of the buyers. The seller’s obligation is exactly the opposite of the buyer’s rights. For example, if a call buyer has the right to buy stock, the call seller must have the obligation to sell stock. If a put buyer has the right to sell stock, the put seller has the obligation to buy stock.

These obligations are really potential obligations since the seller does not know whether or not the buyer will use his option. For example, if you sell a call option you may have to sell shares of stock, which is different from saying that you will definitely sell shares of stock. A call seller will definitely have to sell shares of stock if the call buyer decides to use his call option and buy shares of stock. If you sell a put option, you may have to buy shares of stock. A put seller definitely must buy shares of stock if the put buyer decides to use his put option and sell shares of stock.

It’s important to understand that options only convey rights to buy or sell shares of stock. For example, if you own a call option, you do not get any of the benefits that come with stock ownership such as dividends or voting privileges (although you could acquire shares of stock by using your call option and thereby get dividends or voting privileges). But by themselves, options convey nothing other than an agreement between two people to buy and sell shares of stock.

Now that you have a basic understanding of call and put options, let’s add some market terminology to our groundwork.

The Long and Short of It

The financial markets are filled with colorful terminology. And one of the biggest obstacles that new option investors face is interpreting the jargon. Two common terms used by brokers and traders are “long” and “short,” and it’s important to understand these terms as applied to options.

If you buy any financial asset, you are “long” the position. For example, if you buy 100 shares of IBM, using market terminology, you are long 100 shares of IBM. The term “long” just means you own it. Likewise, if you buy a call option, you are “long” the call option.

If “long” means you bought it then “short” means you sold it, right? Not quite. Some people will tell you that “short” just means you sold an asset, but that is an incomplete definition. For example, if you are long 100 shares of IBM and then sell 100 shares you are not short shares of IBM even though you sold 100 shares. That’s because you bought the shares first and then sold them, which means you have no shares left.

However, let’s say you bought 100 shares of IBM and then, by accident, entered an order online to sell 150 shares of IBM. The computer will execute the order since it has no way of knowing how many shares you actually own. (Maybe you have shares in a safe deposit box or with another broker.) But if you really owned only 100 shares then you would be “short” 50 shares of IBM. In other words, you sold 50 shares you don’t own. And that’s exactly what it means to be short shares of stock. It means you sold shares you do not own. However, when we short shares in the financial market, it’s not meant to be by mistake – it is done intentionally. How can you intentionally sell shares you don’t own? You must borrow them. In order to further understand what it means to be “short” and how that applies to options, let’s take a quick detour to understand the basics of short selling.

Traders use short sales as a way to profit from falling stock prices. Assume IBM is trading for $70 and you think its price is going to fall. If you are correct, you could profit from this outlook by entering an order to “short” or “sell short” shares of IBM. Let’s assume you decide to short 100 shares. Your broker will find 100 shares from another client and let you borrow these shares. Although this sounds like a lengthy, complicated transaction it takes only seconds to execute.

In terms of the mechanics, shorting shares is similar to making a purchase on your credit card. Your bank finds loanable funds from somebody else’s account to let you borrow and you then have an obligation to return those funds at some time. How complicated is it to short shares of stock? About as complicated as it is to swipe a credit card at a cash register.

Let’s assume you short 100 shares of IBM at $70. Once the order is executed, you have $7,000 cash sitting in your account (sold 100 shares at $70 per share) and your account shows that you are short 100 shares of IBM – you sold shares that you do not own. Do you get to just take the $7,000 cash, close the account and walk away? No, once you short the shares of stock, you incur an obligation to replace those 100 shares at some time in the future. In other words, you must buy 100 shares at some time and return them to the broker. Obviously, your goal is to purchase those 100 shares at a cheaper price.

Let’s assume that the price of IBM later drops by $5 to $65 and you decide to buy back the shares. You could enter an order to buy 100 shares and spend $6,500 of the $7,000 cash you initially received from selling shares. Once you buy the 100 shares, your obligation to return the IBM shares is then satisfied and you are left with an extra $500 in your account. In other words, you profited from a falling stock price. This profit can also be found by multiplying the number of short shares by...