![]()

1. SEIZURE

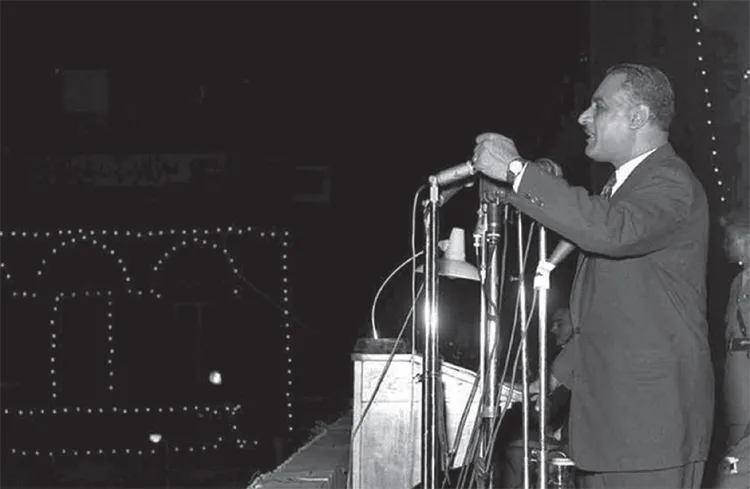

On a sweltering summer evening in Alexandria on 26 July 1956, Egypt’s new president stepped up to a bank of waiting microphones to give the most famous speech of his life. A crowd had crammed into Menishiya Square, sweatily jostling for position as the former army colonel-turned-president raised both arms in greeting to his listeners. Gamal Abdel Nasser wore a suit rather than his military uniform, but he still carried himself like a soldier: broad shoulders back, hair close-cropped above an officer’s moustache. He spoke passionately, frequently raising his clenched left fist at the lectern to emphasize his words. He related the history of the canal, of Egypt’s occupation by the British since 1882, of other wrongs. Voice raised, he urged the crowd,

Britain has forcibly grabbed our rights … The income of the Suez Canal Company in 1955 reached 35 million pounds, or 100 million dollars. Of this sum, we, who have lost 120,000 persons, who have died in digging the Canal, take only one million pounds or three million dollars … We shall not repeat the past. We shall eradicate it by restoring our rights in the Suez Canal.

In short, Nasser asserted Suez was “an Egyptian Canal” and he intended to take it back. While he spoke, Egyptian forces seized control of the canal and the Canal Company’s offices. The coded phrase for the operation to begin was Nasser’s mention of the name of the waterway’s architect: de Lesseps.

That evening, British Prime Minister Anthony Eden was hosting a formal dinner at Downing Street. After an aide brought in the news from Egypt the meal ended early and Eden held an emergency meeting with a few of his Cabinet ministers which went on until 4 a.m. Nasser’s action was, as The Times phrased it the following morning, “a clear affront and threat to Western interests, besides being a breach of undertakings which Egypt has freely given”. The Egyptian president’s takeover of the canal was a potential threat to Britain’s oil supplies, as the country only had six weeks’ reserves, and it was also a profound embarrassment to the nation which had been joint custodian of the canal since its creation and whose soldiers had, until a few weeks before, been its guardians. A determined Eden sent a courteous but clear message across the Atlantic to the White House: “my colleagues and I are convinced that we must be ready, in the last resort, to use force to bring Nasser to his senses. For our part we are prepared to do so.”

The Suez Crisis had begun.

Nasser’s seizure of the Suez Canal was not just a shock to politicians in Britain. When Nasser informed his own ministers on the morning of 26 July what he planned to say in his speech that evening, most sat in stunned silence before asking nervous questions.

Nasser addresses the crowd in Menishiya square. He was an articulate and impassioned speaker.

The Suez Canal at Ismalia.

One told Nasser that if he went ahead, “This decision means that we shall become directly involved in a war with Britain, France and the whole of the West.”

Nasser was unperturbed and replied, “I did not ask you to fight. If war breaks out it will be Abdul Hakim Amir [the Egyptian Army chief of staff] who will be fighting, not you.”

Even for his own ministers, Nasser’s plan to take the canal by force seemed an extreme reaction, but the crisis had been brewing for decades.

The flamboyant nineteenth-century poet and playwright Oscar Wilde quite neatly summed up the canal conundrum. In his 1895 comedy The Ideal Husband – which rather appropriately examines corruption in high politics – one character who is a minister at the Foreign Office remarks, the Suez Canal was a very great and splendid undertaking. It gave us our direct route to India. It had imperial value. It was necessary that we should have control. The comment was a moment of comparative light comedy, but it was a devoutly held view among most of the British establishment for the better part of a century. Anything but British control of the waterway was almost unimaginable. As Eden summarized it in 1929, twenty-six years before he became prime minister,

If the Suez Canal is our back door to the East, it is the front door to Europe and Australia, New Zealand and India. If you like to mix your metaphors it is, in fact, the swing-door of the British Empire, which has got to keep continually revolving.

Nasser was now threatening to jam the door shut.

The problematic issue with keeping the Suez door revolving was that under the terms of agreements already made with the Egyptians, British troops were required to leave by 1956 anyway. And the cost of keeping them there was astronomical. Maintaining control of the canal was expensive and flagrantly imperialist, but the alternative was to risk potential disruption to shipping and the security of Britain’s oil supplies. However, one of the facts often ignored by many historians and commentators is that perhaps the greatest exponent of a more realistic Suez Canal policy on the part of the British government prior to 1956 was Anthony Eden.

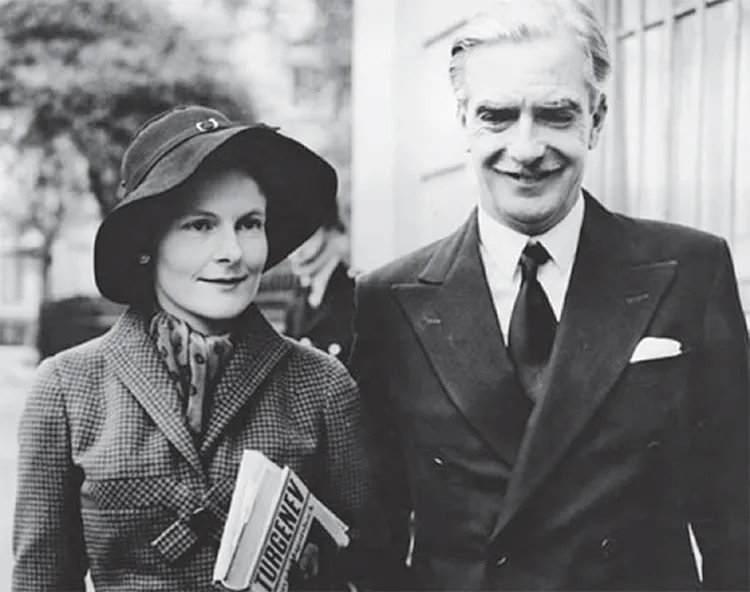

Eden would go on to be widely regarded as Britain’s worst prime minister in modern history, almost entirely because of the Suez Crisis, but the charming, erudite, upper-class Etonian and Oxford graduate was in fact viewed by most as a popular, consummate diplomat when he finally became prime minister in 1955.

Eden had been foreign secretary under Winston Churchill throughout Churchill’s terms in office as prime minister, both during the Second World War and in the 1950s. He began as a firm proponent of the establishment view of the canal and of protecting Britain’s interests military, but over time adopted a more pragmatic desire to reduce Britain’s role. In 1952, while foreign secretary, he wrote a classified memorandum for Cabinet which stated,

British Prime Minister Anthony Eden with his wife Clarissa.

it is clearly beyond the resources of the United Kingdom to assume the responsibility alone for the security of the Middle East. Our aim should be to make the whole of this area and in particular the [Suez] Canal Zone an area of international responsibility.

Far from being an idle whim, the policy of making responsibility for Suez international was one which Eden at least publicly held to for the duration of the crisis and the remainder of his life. The main opposition to his desire to reduce Britain’s commitment in fact came from Winston Churchill. During a fiery Cabinet meeting in the midst of negotiations with Egypt in 1954, Eden pointedly told Churchill in front of his Cabinet colleagues, “In the second half of the twentieth century we cannot hope to maintain our position in the Middle East by the methods of the last century. However little we like it, we must face that fact.”

Eden, supported by Cabinet, prevailed and in 1954 he persuaded Egypt’s new leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, to sign the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, which agreed to the withdrawal of British military forces by 1956, but maintained the canal as an international waterway and the Canal Company in British and French hands. It seemed a perfectly reasonable solution; indeed Nasser himself had told the British newspaper the Daily Mirror a few months before the agreement was concluded, “If this question [of the presence of British forces] were settled, a great friendship could exist between us [Britain and Egypt].”

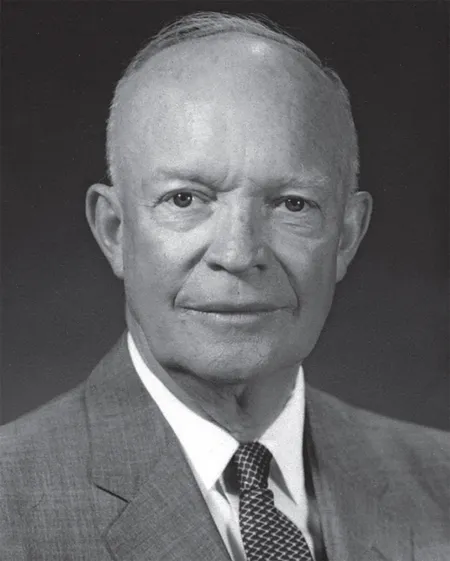

In March 1956 the last British unit, the 2nd Battalion of The Grenadier Guards, departed from Port Said with the final troops leaving in June. The much-angsted-over decision to withdraw British forces was an entirely pragmatic one, but one which even caused its architect concern. In a communication with U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Eden described the military withdrawal as “an act of faith in Egypt”. It was not a widely held faith: as one Conservative MP remarked, “the recent conduct of Colonel Nasser gives nobody any grounds for confidence in him as custodian of an international waterway.”

Nasser also had his own concerns that went beyond the unappealing sight of khaki-clad foreigners standing guard over Egypt’s canal. He had come to power in Egypt through a military coup in 1952 and found himself in charge of a nation with huge domestic problems. The new world into which he led Egypt was one divided between East and West, capitalism and Communism and Egypt was at the centre of the contested region of the Middle East and the location of the crucial canal. Across the world, nations were aligning themselves in the Cold War and when Nasser came to power, conflicts in which combatants were ideologically divided and supported by either Moscow or Washington were raging in Korea and Indochina (Vietnam). Astutely, Nasser played both sides. He purchased Soviet-made weapons via an arms deal with Czechoslovakia while courting the World Bank and the U.S. and Britain for funding for his grand plans to build a dam across the Nile River at Aswan. The project was expected to cost more than a billion dollars. The funding came with the condition that Nasser refuse any aid from the Communist Bloc, but the U.S. State Department decided to use the U.S. chequebook as a weapon to coerce Nasser to align with the West. Apparently out of the blue, although there was mounting domestic political pressure against the Americans paying for an Egyptian dam, the U.S. unilaterally pulled the plug on their part of the funding, collapsing the whole deal. The Egyptian ambassador in Washington was hauled in to see the secretary of state and summarily told the deal was off. As Eden politely later recorded in his memoirs, “We were informed but not consulted and so had no prior opportunity for criticism or comment” – the British prime minister found out from an aide who was reading the Reuters ticker tape – adding, “the news was a wounding to his [Nasser’s] pride.”

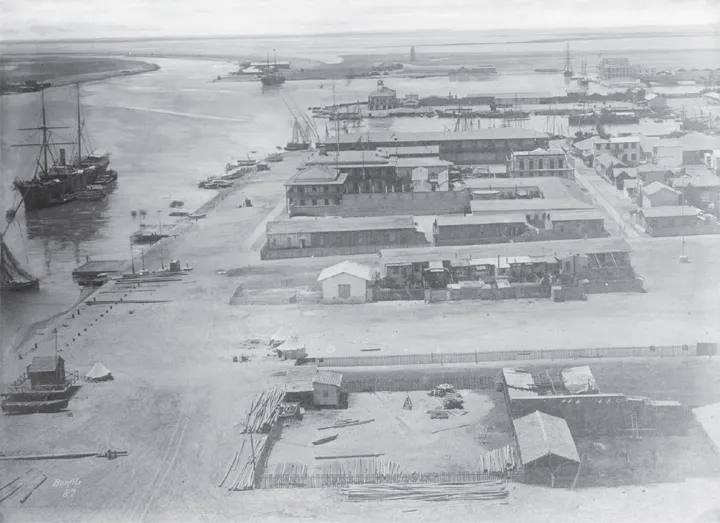

Buildings in the Suez Canal zone, 1910.

The cancellation of the funding for the Aswan Dam was the immediate trigger for Nasser’s decision to take control of the Suez Canal a week later. It perplexed the French foreign minister in particular, as it was the Americans who had killed off the stillborn dam project: “we could not see any reason why Egypt should attack Franco-British interests to avenge itself against an affront inflicted by the United States.”

Nasser cared little for such nuance. To the jubilant crowds crushed close together in the square in Alexandria on the evening of 26 July, he announced that the fees taken from ships transiting the canal would be used to build the dam: “We will build the [Aswan] High Dam and we will get all the rights we lost … [and] destroy once and for all the traces of occupation and exploitation.”

![]()

2. COLONIALISTS AND FASCISTS

In Washington, the perspective on the entire situation was rather different to that in London. Eden’s emergency message to Eisenhower had told the president that Nasser’s action constituted an “immediate threat” to Western Europe’s oil supplies, but for all the bombastic nationalism of Nasser’s move on the canal, the response was not clear cut. The Suez Canal Company was and always had been registered as an Egyptian company and Nasser had promised to compensate the shareholders at market prices for the takeover by the state; the fact was even admitted in the first full meeting of the British Cabinet after Nasser’s announcement, where it was noted in the minutes, “from the strictly legal point of view, his [Nasser’s] action amounts to no more than a decision to buy out shareholders.”

Even the takeover itself was a rather underwhelming moment: an Egyptian captain who was part of the group that entered the Canal Company offices on the night of 26 July later recalled, “we found the French and British and Greeks [employees] were very friendly. We told them, ‘The Canal is nationalized. It belongs to Egypt now. We want your cooperation. The ships must go on moving in the Canal.’ Then we exchanged cigarettes.”

The Suez Canal Company’s offices were located on the waterfront at Port Said.

U.S. president and former wartime general Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Nasser’s action was a shock, but it was not illegal under international law and if the original terms of the de Lesseps canal arrangement were upheld the concession would revert to Egyptian ownership by 1969 in any event. There was outrage in London and Paris, but in Washington, Eisenhower was rather more sanguine. When he first received warning from the chargé d’affaires in London that military action was being considered by Eden’s government he responded that nationalizing the canal “was not the same as nationalizing oil wells” which would run out; rather, the canal was more like a “public utility”. From the outset there was a strong sense in Washington that the response in Britain and France was out of proportion.

It also played into a broader post-war narrative that the old empires were an anachronism that hindered U.S. policy. When U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles visited Egypt in 1955 he noted acidly,

Such British troops as are left in the area are more a factor of instability rather than stability … The asso...