![]()

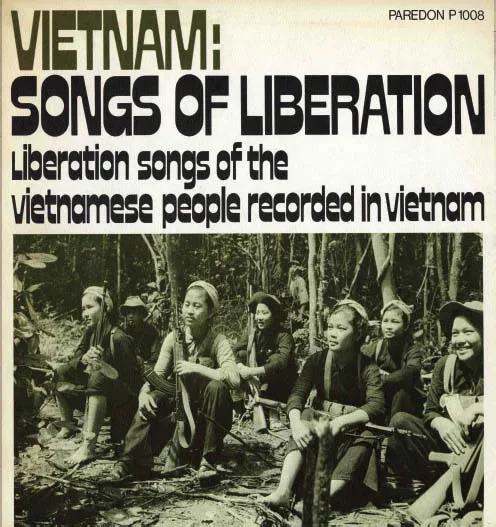

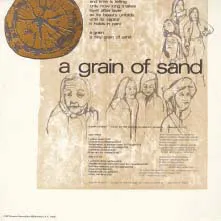

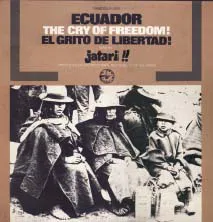

PAR01008, 1971, design by Ronald Clyne, photo by Photo Pic, Paris.

Making Revolutionary Music

Paredon Records cofounder Barbara Dane interviewed by Alec Dunn & Erin Yanke

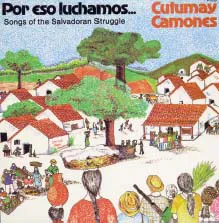

Paredon Records was a left-wing, New York-based record company that released over fifty LPs of international music between 1969 and 1985. The first record’s music was from Cuba and the final record was from El Salvador. Between these two bookends, from revolutionary Cuba in the 1960s to the Central American struggles of the 1980s, Paredon chronicled the turbulent period of Third World liberation movements and the New Left musically.

Paredon was started after Barbara Dane and her husband Irwin Silber visited Cuba in 1967. Dane had been a noted singer of folk, blues, and jazz with several records under her belt. Silber founded the long-running music periodical Sing Out and was a formative figure in New York’s folk scene.

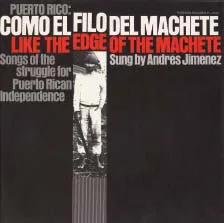

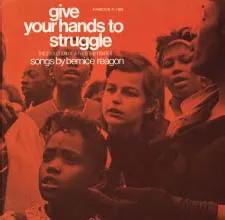

Paredon featured several spoken word records (from Huey, Che, Ho, and Fidel, naturally), but the strength of the label is in its dizzying variety of music: miners’ songs from Chile, sub-rosa recordings by Filipino activists, modern compositions by Mikis Theodorakis, guerilla songs by the Viet Cong, folk-psych records from Cuba, among many, many more. Worth noting as well is the consistently striking cover art and booklet design, the majority of which was designed by Dane and Ronald Clyne (whose work for Folkways and Paredon Records stands out as some of the best American graphic design of the mid-twentieth century).

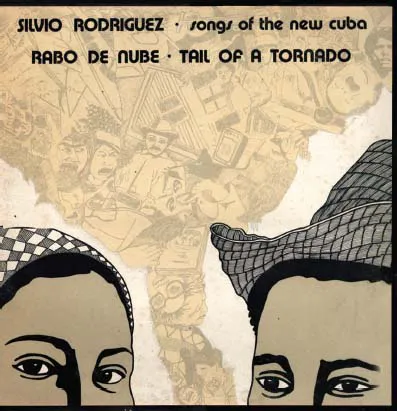

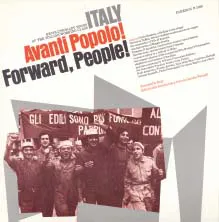

PAR01040, 1978, design by Ronald Clyne.

PAR01050, 1985, cover art by Radio Venceremos System.

We interviewed Barbara Dane over the phone on Christmas Eve, 2012. It was a three-hour interview in which she simultaneously answered questions and orchestrated dinner preparations for a family reunion. A loquacious woman with a beautiful voice, it was easy to see how Dane made lasting contacts with people all over the world: she was funny, forward, and able to stay focused in the midst of chaos.

I wanted to ask you a little bit about your life and career in music and political movements before Paredon …

Because otherwise people will wonder who is this old lady bullshitting …

You started out as a singer?

I grew up in Detroit just after the depression. I went to a public school but it was in the next neighborhood over, where there was money, and in my neighborhood there was no money. My classmates had little starched dresses and Shirley Temple curls that their maids probably combed out for them every morning, whereas we were sent to school in simple woolen things that didn’t have to be ironed and short Dutch bobs that didn’t have to fussed with, because my mom was always working. So I was aware of class differences from the get-go, and I had always wanted to express something for the people around me who didn’t have a whole lot of outlets for expressing themselves. I realized that my strongest tool was that I could sing. I found a really great teacher who was a bel canto teacher, which teaches you that singing comes from the whole body, not from your throat but from the balls of your feet. You have to stand the proper way and use your muscles the right way. So I learned all that stuff but I knew I was not going to end up singing little sopranos, Ave Marias, things like that.

PAR01028, 1975, design by Ronald Clyne.

PAR01020, 1973, cover art by Artist Resource Basement Workshop.

Then I got involved with a bunch of people, some communists, and we got together to challenge the local Detroit racist behavior. Detroit at the time was as much (if not more) segregated then any southern town. You couldn’t go have a cup of coffee with a friend if the friend was the “wrong” color, or you were the “wrong” color. There was a Michigan Equal Accommodations Act, but no one was pursuing it, so we decided to challenge it by going in a group and seeing if they’d serve us at the Barlam Hotel, which was a big old hotel on Cadillac Square with a coffee shop.

My friend was one of the leaders of the pack, a black woman, gorgeous, a little bit older then us. She worked right across the street at the National Maritime Union office. The NMU was one of the more radical unions at the time but she couldn’t eat lunch anywhere around there. We thought we’d do this and afterward she’d be able to eat lunch there. Well, to make a long story short, this guy kicked us out of there, screamed and yelled, and we then pulled together a demonstration. We had church groups and unions and PTAs, whatever, a big picket line, every Saturday. And there I was called upon to lead singing, because I could throw my voice out over the crowd, and I’d sing “We’re Gonna Roll the Union On”—those kinda songs.

PAR01045, 1982, design and art by Juan R. Fuentes.

How long did you stay in Detroit?

I stayed in Detroit until I was twenty. I figured I could make a nickel here and there singing pop songs. Then some promoter calls me and asks if I want to go on the road with some well-known big band, so I went in for the interview. The guy says right away, “Take off your coat and turn around,” and right away I say, “Heh, what’s that got to do with singing?” He says, “Oh, I’ve heard you, you’re a pretty good singer.” I said, “Wait a minute, I think I’m in the wrong place.” So I fled, and right then I understood that basically a young woman was selling her looks and not her gifts or skills. So I didn’t want to be part of that stuff. Which set a tone for … like forever!

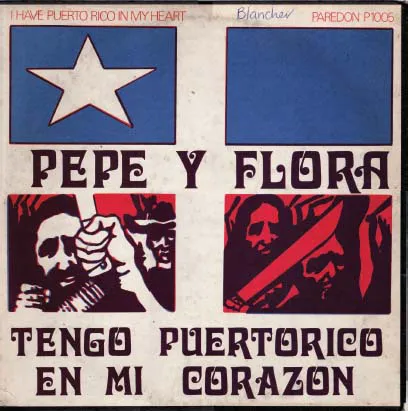

PAR01005, 1971, designer unattributed.

During that time I became pregnant and was forced to look at my life a little bit. I’d hooked up with a man named Ralph Cohn, who was the first man who talked about Marxism to me in concrete terms. We left for California, went to LA, and spent a few months there in dire circumstances. No money, no job, no nothing. And then my mom married someone who lived in San Francisco and invited us up here. I stayed in the Bay Area up until ’64 and during that time was always in a whole mix of trying to make a living with singing and trying to change the world with singing. That’s a pretty tight rope to walk.

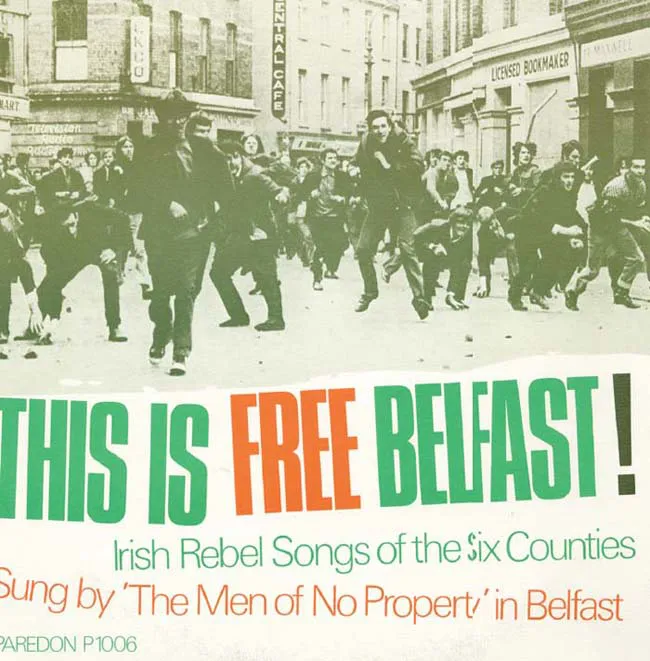

PAR01006, 1971, design by Ronald Clyne.

When you started in the ’40s it was viable for you to be a singing star and a pop singer and also a radical. And then we go into the Red Scare and the blacklist and that period of reaction…. Did you feel that? With trying to perform and get work?

The answer is so big, it’s hard to condense anything. At first I was trying to make connections in the commercial world where I could make a living singing. I was working at a department store, supporting my child, supporting my husband too (who was not much of a breadwinner). So, back then they had amateur shows on the radio. TV was just starting and there were contest on there too. One of the contests was called Miss U.S. Television! Here I was, having to walk across the stage in a bathing suit and high heels with a banner across the front of me, and singing my folk songs for my talent, like a Miss America pageant, which was totally anathema to me, but I won, and the prize was a 13week series on TV. So I had a TV show. Looking back—that was the first time folk music was on TV that I’m aware of, even including New York or anywhere. So I went and did my little show: Miss U.S. Television. But TV at the time was still a little industry. By this time I had switched husbands, and I was pregnant with my second child. So I had to drop out just as I was beginning to be pretty well known.

PAR01034, 1976, design by Ronald Clyne, photo by El Punto.

PAR01026, 1974, design by Ronald Clyne, photo by Nancy Van Wicklen.

The Weavers on the East Coast were a big sensation, making big hit records. A producer at the time wanted me to form a group because he was thinking if we had a West Coast group similar to the Weavers then we could really make it. After getting past the pregnancy, I did form a group and it was a pretty great group, but we had some differences and I didn’t go on with them. So I went waltzing on back to my political life and I also went on to be a jazz singer just because the music interested me.

And you had some records out around that time, right? I read somewhere that you’d sang with Louis Armstrong, and didn’t you have a record with Lightnin’ Hopkins?

That all comes a little bit later. The traditional jazz world to me was glorious. I loved the music, I loved being out in front of a band. It was a whole exhilarating experience for a solo singer. I did make a record right then, my first album. It was called Trouble In Mind. From that record I was asked to come down to LA and make a single, which I did, called “On My Way.” And it was a pretty successful. Once you had a breakout locally, then the majors started to look at you, and Capitol noticed me and I made an album for them. I signed to them and was supposed to make a bunch more. The first album did pretty well, and then here’s what happened. At some point I did a concert at the Pasadena Playhouse, opposite Louis Armstrong and his band. I was singing with the Firehouse Five, and Louis heard me singing. He appreciated what I was doing and he asked me to do a tour in Europe with him. I was, of course, thrilled. That would be the epitome of any blues singer’s work. I was all set to go on that tour and all of a sudden the phone doesn’t answer when I call. I didn’t receive any mail from anyone. Everything got cut off all of a sudden. Sharply. Nobody ever explained anything. Communication just completely shut down. I never went on the tour. At the time Louis was called Ambassador Satch and he was doing all these State Department tours. It seems that the State Department people took notice of my notoriety in the poli...