![]()

Kommune 1 in 1967, photographed by Thomas Hesterberg.

1.

On the evening of April 5, 1967, West German police kicked down the door of Uwe Johnson’s apartment, a prominent novelist. Inside they arrested eleven members of Kommune 1, a radical student group, who had taken up residence in the apartment during the novelist’s absence and were in the process of measuring and mixing “unknown chemicals” into plastic bags. The American vice president Hubert Humphrey, was to arrive in Berlin the following day and give a speech at the Schöneberg council house, nine blocks from the apartment. Police claimed they had foiled an assassination attempt, and the German press described an international conspiracy by a “Horror Commune” of young radicals. Rumors ran wild. Chinese agents in East Berlin had supplied the explosives. The Maoist students were following orders from Peking.

The police arrested a few more students in the following days, and all were charged with conspiracy to commit murder. The unknown chemicals, however, turned out to be ingredients for buttermilk pudding, which the communards planned to throw at the vice president and the whole affair became known as the “Pudding Plot.” The initial charges were reduced to plotting a criminal assault and eventually all the students were acquitted. They denied direct political motivations for their actions but others drew it for them. Ulrike Meinhof, then a columnist for the left-wing journal Konkrete, wrote, “It is considered rude to pelt politicians with pudding and cream cheese but quite acceptable to host politicians who are having villages eradicated and cities bombed.”

Fritz Teufel in Kommune 1, photograph by Werner Kohn

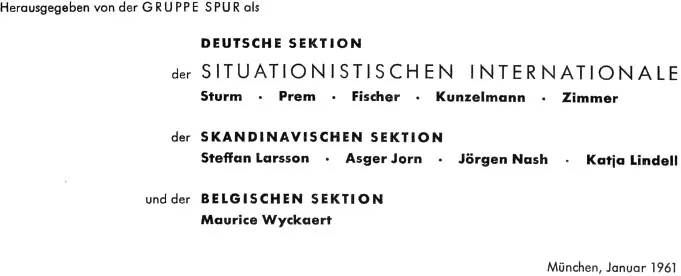

Flier produced by SPUR, 1961.

2.

Sometimes small groups act at just the right moment to channel a great rush of history or bring together disparate but important historical actors, and Kommune 1, or K1, seems that way. Their brief experiment in provocation and communized living merged art practices and the political, the performative, and the actual. What started as pure theater ended in spectacular reality—but in those early years, before the climax of 1968—the future leaders of the New Left and the German Autumn alike cut their teeth on Dadaist agitation.

In the years after the Second World War, Western European countries made massive gains in living standards and economic growth. West Germany bounced back from war and division to lead the continent in industrial production and GDP—what is called the Wirtschaftswunder or economic miracle. During this growth, social democracy and moderation served as buffers against the extremes of right and left wing politics. But along with these liberal economic policies came a stifling social conservatism, re-entrenching values of work, church, and family. The 1968 generation grew up with this odd paradox of economic prosperity and social glaciation, always haunted by the bitter aftertaste of National Socialism.

Postcard produced by SPUR

Out of this seemingly static landscape Kommune 1 appeared to emerge from nowhere—a new and terrifying phenomenon. But it was, as political projects always are, part of a continuity of actions, ideas, and experiments. Dieter Kunzelmann traversed this continuity, starting with the K1’s artistic origins and continuing with its connection to terrorism. At the time of the Pudding Plot trial he was twenty-eight, older than most of his codefendants, and his bald crown and shaggy features distinguished him from the band of rather clean-looking students. He was seasoned in aesthetic political action, having begun nearly a decade before down the path to radicalism. After dropping out of high school, he fell in with the Munich-based, German wing of the Situationist International, called the SPUR Group, which edited a journal of the same name. They asked him to write for the journal, and Kunzelmann’s propensity for confrontation with authority led to the print run of an entire issue being seized as obscene. Guy Debord supported SPUR during the obscenity trial but expelled them from the International a year later, accusing them of “a systematic misunderstanding of Situationist theses.” Around the same time, Kunzelmann also broke with the SPUR to form the more action, and actionist, oriented Subversive Aktion.

Sensing some potential, the editorial group behind Subversive Aktion moved en masse to West Berlin. The city was still very empty from war and division, and its special status as an occupied zone meant that West German men who lived there were exempt from compulsory military service. This brought young West Germans to the city in droves, many of whom enrolled in the Freie Universitat and started to question the world they were inheriting, a world deeply scarred by the legacy of totalitarianism and advances in technology and bureaucracy. The U.S. was already involved in Vietnam and using West German airbases to ferry soldiers and munitions to support the South Vietnamese regime, and opposition to the war was growing amongst the students. In this milieu, Kunzelmann befriended Rudi Dutschke, a young East German refugee studying at the Freie Universitat. One night after attending a lecture by Ernst Bloch, the pair watched the new Louis Malle film Viva Maria! and were so taken by it that they went back to see the film every night that week. With other students from the Freie Universitat and future K1 leader Dorothea Ridder, they formed a group called Viva Maria.

Dieter Kunzelmann.

In 1965, Dutschke joined the Sozialistische Deutsche Studentenbund (SDS, German Socialist Student Union), the most influential student organization in West Germany. Kunzelmann joined as well and they created a commune/working group with several other students to formulate how to make new living situations. They discussed breaking with authoritarian family structures and monogamous relationships as a necessary precondition for revolutionary action. They talked about setting up their own commune, and Kunzelmann even wrote a treatise on the subject: “Notes for Establishing Revolutionary Communes in the Metropole.”

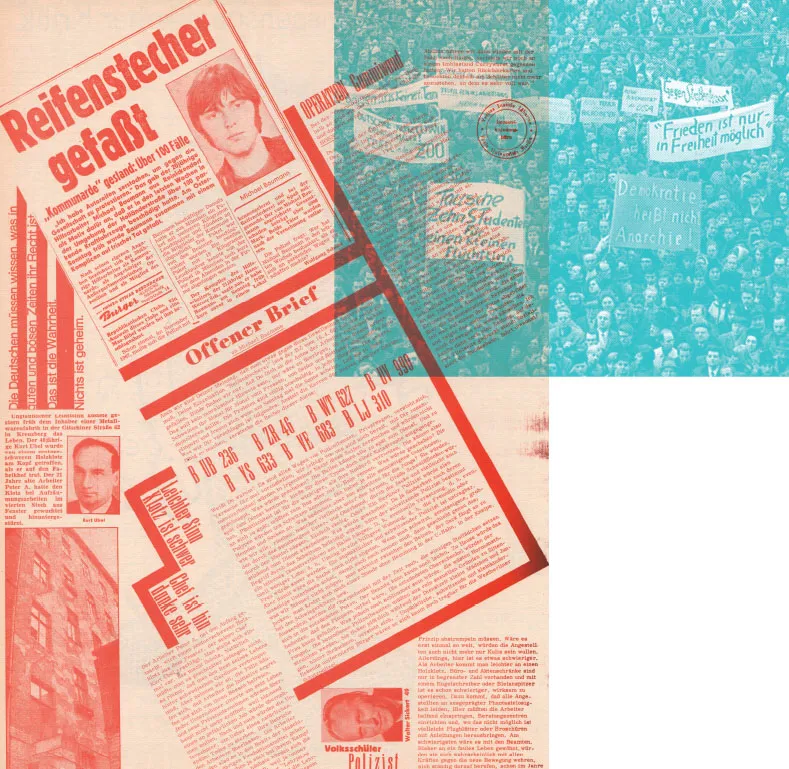

Cover of Linkeck #1, 1968

Sit-in by K1 at the Schöneberg government house demanding Fritz Teufel’s release, 1967.

Linkeck #1

A large anti-war demonstration in Berlin under the banner “Berline stands for peace and freedom,” 1968

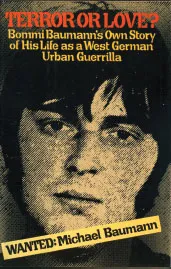

First English edition of Baumann’s Terror or Love?, published by Grove Press

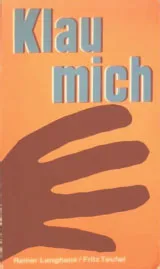

Cover of the first edition of Klau Mich.

When Ridder and Kunzelmann sought to put these discussions into practice, Dutschke balked and they invited other people instead. Rainier Langhans, a law student, joined the project, as did Dagrun and Ulrich Enzensberger (ex-wife and brother of prominent novelist Hans Magnus Enzensberger), who helped secure the commune’s place in Uwe Johnson’s apartment. Once settled, the communards pushed to break with bourgeois norms. As with most of the New Left, they fell heavily under the theories of the Frankfurt School, especially the anti-authoritarian bent of Herbert Marcuse, but were also enthralled with Wilhelm Reich’s theories of sexuality and authority. Their hair got longer and they advocated a communism of goods and free love—all doors were removed and the communards all slept in one large room. This intensity of communalism—pushed by Kunzelmann, Langhans, and the newly arrived Fritz Teufel, the patriarchs of the commune—brought more members and attention to the group but also drove several away. Tales of orgies were surely exaggerated for and by the tabloid media, but monogamy was definitely frowned on, especially when a woman did not want to sleep with a man in the commune. This led to an unfortunately common dynamic where most women (with the exception of the founding members Dagrun Enzensberger, Dagmar Seehuber, and Dorothea Ridder) were reduced to the role of groupies and girlfriends, or pushed out for not being sufficiently “sexually liberated.” Some started other communes around the city. A girlfriend of Rainer Langhans, Antje Krüger, left him and K1 to form another commune (and publication) called Linkeck, less focused on sex than an equal division of labor and the abolition of property. Michael “Bommi” Baumann joined K1 after befriending them in SDS, but also moved on to other groups. The future leaders of the Red Army Faction, Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin, often hung around the commune. Ensslin was then an earnest student activist and Baader a petty thief with a tast...