![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Minority as the Protagonists

Revisiting Ru 儒 (Confucians) and Their Colleagues under Emperor Wu (141–87 BCE) of the Han1

Students of Chinese history probably are all familiar with a well-known narrative, easily summarized as “the victory of ru” in the Han. In this narrative, the Warring States period, when the Hundred Schools flourished, has usually been depicted as the distant background, while the short-lived Qin 秦 dynasty (221–207 BCE), which is said to have cruelly oppressed scholars and their teachings, has played the overture. The early Han court, commonly described as dominated by Huang-Lao 黃老 thought, has become a proscenium. Through dramatizing the struggles between followers of Huang-Lao thought, represented by Empress Dowager Dou 竇太后, and supporters of ru learning, represented by Emperor Wu, this thesis portrayed the elevation of ru as a theater piece.

Over the past decades the occasional voice has openly challenged the idea that Han ru routed their court rivals.2 For example, some scholars contend that Emperor Wu failed to promote pure ru learning—he too embraced Huang-Lao doctrines and Legalist teachings.3 Some recognized that few of Emperor Wu’s political polices—economic, military, even religious—bore the stamp of Confucianism.4 Recently, Michael Nylan and Nicolas Zufferey have demonstrated that in the Han there was no distinctive group called Confucians with a distinguished ideology. Instead, those who called themselves ru in Han times were a heterogeneous group with varying intellectual orientations; some were not even followers of Confucius.5

But if we cannot define ru according to a shared doctrine or moral code, why did Sima Qian classify some of his contemporaries into one group, call them ru, and define them as the followers of Confucius, and thereby set them apart from the rest of the officials of the day? What was the implication of such a category in social terms?

In order to answer these questions, I will look beyond the contentions between different intellectual discourses, beyond the materials strictly relevant to ru. This chapter will investigate the social origins and intellectual orientations of eminent officials during Emperor Wu’s reign to assess the positions those called ru occupied in the power hierarchy. It will demonstrate that ru, the protagonists in the dominant narrative, were in fact a small minority on the political stage during Emperor Wu’s rule. Based on these observations, I will proceed to ask why the conventional wisdom has habitually devoted full attention to these few ru, who occupied a tiny fraction of the high-level posts, and therefore mistakenly claimed the triumph of ru. I will further demonstrate that traditional perception and representation of Emperor Wu’s reign are profoundly shaped by two chapters of the Grand Scribe’s Records (Shi ji 史記): namely, the displaced chapter “The Basic Annals of Emperor Wu” (Xiaowu benji 孝武本紀) and “The Collective Biographies of Ru” (Ru lin lie zhuan 儒林列傳).6

RU, A MINORITY GROUP

Several famous stories are often cited by scholars dealing with the political and intellectual history of Western Han. For example, Dowager Empress Dou, a faithful follower of Huang-Lao thought, tried to punish Yuan Gu 轅固, a ru, because she disliked the ru learning. Emperor Wu employed Zhao Wan 趙綰 and Wang Zang 王臧, two ru, to implement certain ritual practice, and promoted Gongsun Hong 公孫弘, an expert on the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu 春秋) (hereafter, Annals) from humble circumstances to prominence. Rather than looking only at the activities of these ru officials, I would like to ask who were the colleagues of Gongsun Hong, Zhao Wan, and Wang Zang; what features characterized the high officials who directed the state apparatus; what factors contributed to their success in the officialdom.

In “A Chronological Table of Famous High Civil and Military Officials since the Founding of the Han” (Han xing yilai jiangxiang mingchen nianbiao 漢興以來將相名臣年表) of The Grand Scribe’s Records, appear the names, terms of appointment, and dates of death or dismissal of the Chancellors (Chengxiang 丞相), Commanders-in-chief (Taiwei 太尉; later the title was changed to Dasima 大司馬), and Grandee Secretaries (Yushi dafu 御史大夫), known collectively as the Three Dukes (Sangong 三公). The latter were employed between the establishment of the Han dynasty (206 BCE) and the middle of the reign of Emperor Yuan 元帝 (20 BCE).7 This information is supplemented by the chapter “A Table of the Hundred Officials and Dukes” (Baiguan gongqing biao 百官公卿表) of The History of Western Han (Han shu 漢書), which provides, in addition to information regarding the Three Dukes, the names and dates of the appointments and deaths or dismissals of the Nine Ministers of the State (Jiuqing 九卿), noted generals, and senior officials of the metropolitan area.8

With power second only to the emperor’s, the Three Dukes occupied the apex of the Han bureaucracy. The Nine Ministers constituted the second highest stratum.9 The senior officials of the metropolitan area, as the candidates for the positions of the Nine Ministers, enjoyed status equal to or slightly lower than the Nine Ministers.10 In addition to their administrative titles, officials in the Han court were also ranked in terms of bushels of grain, ranging from 10, 000 bushels to 100 bushels. It is said that the Three Dukes were ranked ten thousand bushels, while the Nine Ministers and senior officials of the metropolitan area fully two thousand bushels. These three groups comprised the most eminent officials of the imperial bureaucracy.11

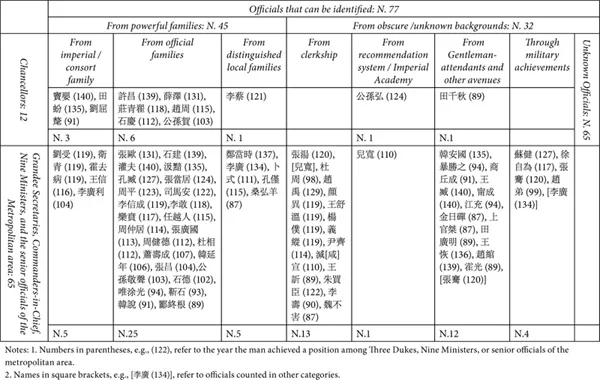

During the fifty-four years of Emperor Wu’s rule, 141 people reached these eminent positions. Collecting information scattered throughout The Grand Scribe’s Records and The History of Western Han, it is possible to identify seventy-seven people’s social origins, career patterns, intellectual orientations, and social networks; these are illustrated in table 1.1 (see also chart 1.1).12 An analysis of the above information provides us a clear picture of who was operating the state apparatus on a daily basis.13

BACKGROUNDS OF EMINENT OFFICIALS

Under Emperor Wu there were twelve chancellors. Among them, three belonged to empresses’ families or the imperial family proper; six were descendants of high officials.14 Of the latter six, four were either the sons or grandsons of men who helped establish the Han and four were ennobled because of their military accomplishments. The remaining three men were Li Cai 李蔡, Tian Qianqiu 田千秋, and a famous paragon of ru, Gongsun Hong. Li Cai came from a military family: one of his ancestors had served as a general in the Qin state, and one of his cousins was the famous general Li Guang 李廣. Tian Qianqiu had been a Gentleman-attendant serving at Emperor Gao’s shrine (Gaomiao qinlang 高廟寢郎)—his social origin is not clear.

Chart 1.1 Unknown and Identifiable High Officials under Emperor Wu

Table 1.1. High Officials under Emperor Wu (141–87 BCE) 武 帝 (公 元 前 141–87) 一 朝 三 公 九 卿 統 計

Compared with the chancellors whose families had occupied a place near the top of the power pyramid for decades, Li Cai’s and Tian Qianqiu’s backgrounds were modest. But compared with Gongsun Hong, they stood high. According to Sima Qian, Gongsun Hong had been dismissed from a clerkship he had held in a prison at Xue (Xue yuli 薛獄吏); so poor was he in his youth that he had herded pigs.

By and large, family background dictated one’s future in Han China, and this was especially true of high officials. We know little about how Chancellor Liu Qumao 劉屈氂 climbed to the top of the imperial bureaucracy; the record tells us only that he was the son of Liu Sheng 劉勝, a half brother of Emperor Wu. Chancellor Tian Qianqiu’s path to glory must have struck his colleagues as eccentric. Pleased by a one-sentence memorial from a Gentleman-attendant at Emperor Gao’s shrine, the seventy-year-old emperor promoted Tian Qianqiu from his lowly post to the office of Grand Herald (Dahong lu 大鴻臚)—thereby making him one of the Nine Ministers. A few months later Wu appointed Tian Chancellor. Ban Gu reported that on hearing this story, the leader of Xiongnu 匈奴, entitled Chanyu 單于, derided the Han court for not employing a worthy fellow.15

Seven of the men who served as Chancellor had held illustrious positions and exerted considerable influence in court long before Emperor Wu succeeded the throne. Xu Chang 許昌, Xue Ze 薛澤, and Zhuang Qingdi 莊青翟 had all inherited their grandfathers’ noble status during the reign of Emperor Wen 文帝 in the early 160s BCE. Dou Ying 竇嬰, Tian Fen 田蚡, Li Cai, and Shi Qing had ascended to official positions ranked two thousand bushels, the second-highest rank, during the reign of Emperor Jing 景帝. Because his father had served the throne with distinction, Zhao Zhou 趙周 had been ennobled in 148 BCE. Gongsun He 公孫賀, whose father was once ennobled as marquis of Pingqu 平曲 because of military achievement, served as a retainer of Emperor Wu when the emperor was still a crown prince and was appointed Grand Coachman, one of the Nine Ministers, in 135 BCE.

Not expected to have outstanding performance, innocent descendants of meritorious officials of previous courts, especially of the founding father, naturally served as candidates for Chancellor. This practice had been followed by Emperor Wu, as Sima Qia...