eBook - ePub

Rhyme and Meaning in Richard Crashaw

Mary Ellen Rickey

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Rhyme and Meaning in Richard Crashaw

Mary Ellen Rickey

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Richard Crashaw's use of rhyme is one of the distinctive aspects of his poetic technique, and in the first systematic analysis of his rhyme craft, Mary Ellen Rickey concludes that he was keenly interested in rhyme as a technical device. She traces Crashaw's development of rhyme repetitions from the simple designs of his early epigrams and secular poems to the elaborate and irregular schemes of his mature verse.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Rhyme and Meaning in Richard Crashaw est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Rhyme and Meaning in Richard Crashaw par Mary Ellen Rickey en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Littérature et Critique littéraire anglaise. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

LittératureSous-sujet

Critique littéraire anglaise1

CRASHAW’S RHYME VOCABULARY

THE INTRICACY of Crashaw’s rhyme patterning bears testimony to the interest which he must have had in rhymes as such. This poet, like many of his immediate predecessors—notably Herbert—placed great emphasis on line endings and the shaping effect which they could be made to give to his verses. Most Crashaw commentators have noticed his rhymes and used them as just another bit of evidence to support their diagnosis of him as a “Baroque” writer. Yet two striking characteristics of these rhymes have apparently gone unobserved: first, the fact that his favorites, the ones which he repeats most frequently, comprise a small vocabulary that he uses very little in the beginnings and middles of his lines; and second, that he has to an uncommon degree favorite rhyme combinations and sequences which appear to have well-defined associations for him.

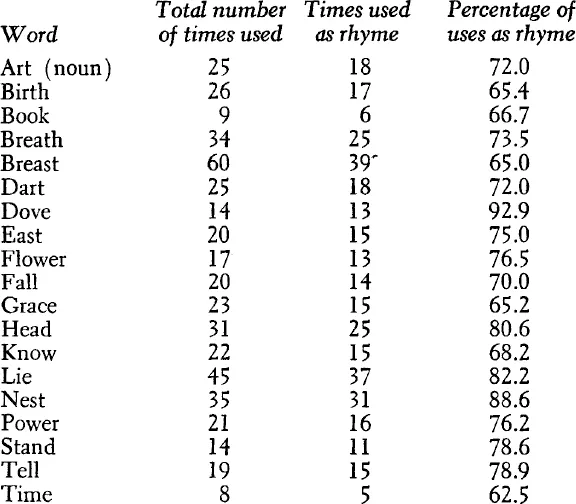

First, to the matter of the discrete rhyme and nonrhyme vocabularies. Here, for example, are a few words which belong to the former.

Surely it is noteworthy that Crashaw uses these words (and they are but a sample) predominantly as rhymes, whereas, since they are quite typical of his erotic-religious vocabulary, one might expect them to appear as frequently in a nonultimate position. Evidently the poet thought of them as rhymes primarily, and only secondarily as ordinary words.

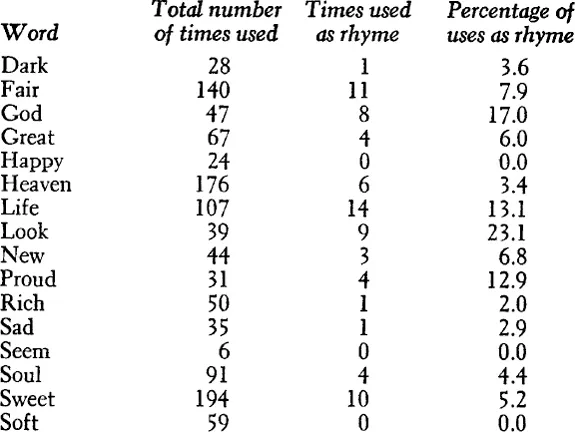

Conversely, Crashaw uses many words as staples of the inner part of the line but rarely as endings. See a few:

It might at first be thought that these differences in proportion result from the difficulty of finding rhymes for some of the words. This difficulty probably accounts at least partly for the infrequent use of some of them—rich and dark, for instance—although Crashaw usually shows no hesitation to contrive unusual compounds to sustain a desired rhyme. Evidently the man would rhyme beauty, duty, and shoo-ty (Wishes to his Supposed Mistresse) could have devised some phrase to match happy. Yet scarcity of rhyme counterparts cannot be offered as an excuse in the case of sad, sweet, and seem, or of look, whose rhyme counterpart book appears almost exclusively as a rhyme word. Nor is there any good reason for his using dove, nest, and the like preponderantly as rhymes. One must simply conclude that Crashaw had a special rhyme vocabulary because he chose to do so, that he gradually separated the two line positions in his mind and relegated certain words to each. Examination of his rhyme vocabulary leads to two further conclusions: first, that he knowingly or unknowingly adopted as rhyme words staple words of the other verse of his time; second, and more important, that certain rhyme pairs and rhyme sequences acquired personal meanings for him which, through a kind of intellectual and emotional necromancy, he could evoke from poem to poem simply by repeating the rhymes which he originally attached to them.

The first of these statements needs little proof. Any reader of Renaissance verse can name a score of words used more than once as rhymes by Southwell, Donne, Herbert, and Herrick—words like love and heart. The very fact that they are used as rhymes, and so have a conspicuous position in the line, renders them memorable. Crashaw’s fellows, however, use these and other favorite rhyme words liberally in the body of the line. Herbert, for example, uses love 122 times in his verse, but only 28 times as a rhyme word. And he does not have any set rhyme counterpart for it: he pairs it with eleven different words, move being used most often, nine times. He uses heart, which has fewer possible rhyme complements, 120 times but as a rhyme only 35 times, matching it with eight different words (part, apart, art, dart, depart, smart, impart, and desert). These are not, then, used disproportionately often as rhymes by Herbert, nor are they regularly paired with the same words. The same is true of that more mechanical rhymer, Herrick: he uses love 348 times in the Hesperides and Noble Numbers, but only 58 times as a rhyme. That Crashaw would have found certain words so frequently in the verse of his time surely had at least something to do with his using them, but not necessarily with his dividing them into rhyme and nonrhyme groups.

The second observation, that certain rhyme combinations accumulated specific associations for Crashaw, must be illustrated at some length from his verse. A reading of almost any handful of the poems leaves one vaguely aware of the repetitions of nest and breast as rhyme words, which separately were commonplaces of Renaissance verse. An actual count of these rhymes in Crashaw’s work reveals that breast is used thirty-nine times and nest twenty-nine times. They rhyme with each other thirteen times and in the rest of their appearances are linked with east, feast, guest, and rest. This group of words may be found in a variety of Crashaw’s poetic contexts, and using them was apparently a strongly ingrained habit for him. In several of his early nest-breast rhymes—and, as will be shown presently, the problem is not peculiar to this pair—there is no logical or even syntactical connection between the two words. Having used one, Crashaw seems automatically to try, at least, to use its mate. In the Sospetto, for example, the King of Death surveys the earth during the birth of Christ:

Hee saw the Temple sacred to sweet Peace,

Adore her Princes Birth, flat on her Brest.

Hee saw the falling Idols, all confesse

A comming Deity. Hee saw the Nest

Of pois’nous and unnatural loves, Earth-nurst.(113)1

Here there is no question of any significant relationship between the two words. The nest is not, clearly, a part of the breast of the temple. The significant relationship between the words is in Crashaw’s mind and here affects the vocabulary, though not the dialectic, of the poetic line.

One finds many such major words in Crashaw’s rhyme vocabulary which, like nest and breast, form stable groups. Another is the blood-flood-good family, equally common in the non-Crashavian verse of the time, and not a surprising one for Crashaw in view of his usual subject matter. Blood occurs thirty-one different times as a rhyme word; flood, twenty-one; and good, twenty-two. Blood and flood are used together in nine places, and blood and good rhyme nine times also. As a rule, flood and blood have a simple and direct association for Crashaw and are an important component of several of his meditations on the Circumcision and Crucifixion, the wounds of Saint Teresa, and the massacre of the innocents. His epigram Vpon the Infant Martyrs is, like several others, constructed around the sum of these two words:

To see both blended in...