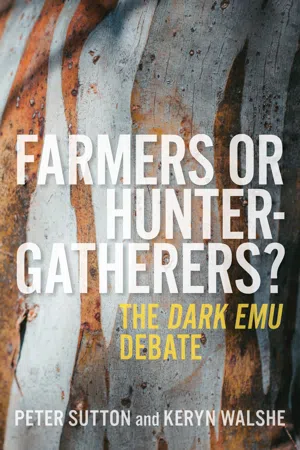

![]()

1

The Dark Emu debate

This book is about a debate over how Australia’s First Peoples lived, and made a living economically, before conquest by the British Empire. Were they farmers, hunter-gatherers, or something in between?

The issues have come to be debated by a wider than merely academic public since Bruce Pascoe published his book Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? in 2014. Here, Dr Keryn Walshe and I approach the relevant facts and interpretations from a scientific and scholarly point of view, as free as possible from identity politics and racial polemics.

I have described our focus as on Australia ‘before conquest’, not ‘before settlement’, for some very good reasons. Australia was not ‘settled’ in or after 1788 by British, Asian and other non-Aboriginal people, as if the lands were void of human societies. ‘Settlement’ is accurately applied to the occupation of previously uninhabited lands, such as the Norwegian migration to Ísland (Iceland) and the Māori migration to Aotearoa (New Zealand). It is not an accurate description of the uninvited imperial British invasion of Australian First Nations’ territories, followed by the subjugation and displacement of the Indigenous Australians who were the lands’ owners. While this usurpation was happening, Aboriginal land tenure systems were ignored—and replaced, in the eyes of the colonials, by property laws imported from England. It was not until 1992 that Australian law recognised that pre-existing Indigenous titles of 1788 could, to varying degrees, have survived these usurpations, and the living native-title holders of certain lands and waters could be acknowledged as such.

The real ‘discoverers’, ‘pioneers’ and ‘early settlers’ of Australia— the people who actually ‘opened up the country’—were the people who arrived around 50,000–55,000 years ago (see Appendix 1), when what are now New Guinea, mainland Australia and Tasmania were a single landmass known today as Sahul. They are rightly called the First Australians, and their descendants have in recent years been accurately referred to as First Nations People. For longer, in recent centuries, they have been known as Aborigines or Aboriginal people. These terms also refer to First People, because they derive from the Latin expression ab origine, which means ‘from the beginning’. There is therefore nothing at all disrespectful about ‘Aboriginal’ as a term, and we use it here accordingly. It stresses primacy. We also refer to the pre-colonial Aboriginal population as the Old People, because that is what their descendants commonly call them, and because it also is a term of respect.

Our subject is a now-famous book about Australia’s First People and their way of life before conquest: Dark Emu, by Bruce Pascoe.1 In Dark Emu, Pascoe sets out to overthrow what he regards as the falsities of past accounts of classical (that is, pre-conquest) Aboriginal ways of life. He argues that, in contrast to what most Australians have been told and believe, at the time of European invasion Aboriginal Australians practised agriculture, stored food, built and lived in large numbers in substantial dwellings and permanent villages, and sewed clothes. He argues further that Aboriginal people having lived in this manner constitutes evidence of their ‘advancement’, of a ‘level of development’ that has not previously been recognised. He writes to correct these untruths and enlighten his readers.

We contend that Pascoe is broadly wrong, both about what Australians have been told of pre-conquest Aboriginal society and about the nature of that society itself. We also take issue with the notion that recognisably European ‘settled’ ways of living, focused on material and technical ‘development’ in food production, are in any way to be valued more than the ways of living that existed in Australia before invasion. In the light of these contentions, and the extensive evidence we present in support of them, we ask how and why Dark Emu has become the phenomenon that it has. Is it time for all Australians to take more responsibility for learning about Aboriginal society, and to demand more careful attention to questions of historical and other truths?

Throughout Dark Emu, Pascoe puts a high value on technological and economic complexity as a standard of a people’s worth, and then seeks out examples of these complexities in classical Aboriginal life. In his words, such complexities are signs of ‘advancement’. He doesn’t employ a term for lack of advancement except for the ‘social backwardness’ he says others have attributed to a perceived lack of pottery and storage among Australians before conquest. He says, ‘This attitude prejudices opinion about the level of development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ (page 105).

As noted, the key areas in which Pascoe seeks to find corrective examples to false estimates of this ‘level of development’ are agricultural food production and storage, substantial dwellings, settlement in permanent villages, high numbers of people in the villages, and the sewing of clothes. The evidence he provides for these subjects is selected in such a way as to compensate for what he believes is a falsely assumed simplicity or crudity—even a ‘brutishness’ (page 100) before conquest by the British Empire—attributed to Aboriginal people by today’s Australians.

All of these subjects belong to the world of the material. For that reason, they may be more readily grasped by the average reader than the complexities of Aboriginal mental and aesthetic culture: those highly intricate webs of kinship, mythology, ritual performance, grammars, visual arts and land tenure systems. Dark Emu does not enter into the non-physical complexities to any real degree. Like its major sources, Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth2 and Rupert Gerritsen’s Australia and the Origins of Agriculture,3 it is largely confined to material economic behaviour and often separated from meaning, from intent, from values, from culture, from the spiritual, and from the emotional. This disconnect, we suggest, is the book’s biggest gap.

In the present book, Keryn Walshe brings to her chapters (12 and 13) a wealth of scholarship and field site work with Aboriginal collaborators, as an archaeologist.

My own contributions draw on wide reading in the anthropology and linguistics of Aboriginal Australia, but, most importantly, are derived from facts and insights I have been given directly by senior Aboriginal people of knowledge. I am here passing these on, and as such, giving back. Over the past fifty years I have been carrying out collaborative research with Aboriginal people, in many cases in remote regions, including Cape York Peninsula (CYP), western Arnhem Land, Daly River, the Murranji Track, Central Australia, and the corner country of the Lake Eyre basin. I have also worked with people in urban and rural regions. In three cases (eastern Cape York, western Cape York, and north-central Northern Territory), I have been taken as a son by senior men and incorporated into their families (Johnny Flinders, Victor Wolmby, Pharlap Dixon Jalyirri). I have given the names and language groups of my principal teachers in the Acknowledgements. Under the tutorship of those Aboriginal mentors, I have recorded, on site, several thousand places and their cultural and historical significance, including in many cases their botanical and faunal resources and how those resources were garnered and in what seasons. Three men of highly specialised botanical learning stand out: Noel Peemuggina and Ray Wolmby (Wik people, western CYP), and Pompey Raymond (Jingulu, Murranji Track region, Northern Territory).

I have recorded many Aboriginal languages and learned to speak three by month after month sitting at the feet of teachers whose languages were still spoken, yet unwritten. And—I note this as it is relevant to later discussions—I’ve done my share of hunting and foraging in days gone by, when I was the only non-local person living with Wik people for months in the wetlands country north of the Kendall River in CYP in the 1970s. All of our protein and fat came from hunting.

The positive contribution of Dark Emu

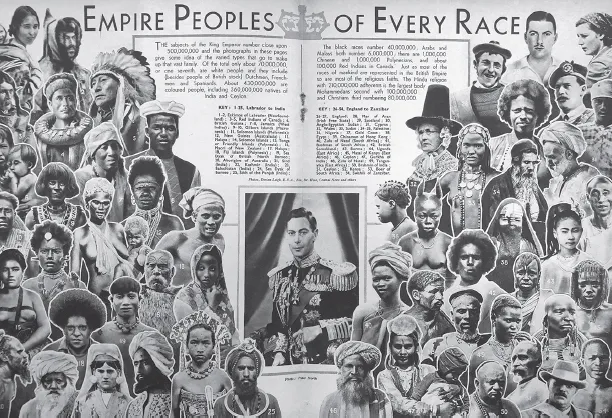

Through Dark Emu, Pascoe has engendered much interest within Australia in the history of the nation, the traditional ways of life of Australian Aboriginal peoples, and past and present relations between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians. He builds awareness of the fact that British Empire colonists in Australia assumed their own superiority and justified conquest, slaughter and massive land theft on that basis (pages 12–13, 154). Internationally, the British Empire was the greatest kleptocracy in human history (see opposite).4

Pascoe popularises the work of Bill Gammage on the evidence for pre-1788 environmental management, principally through the use of fire, and on related topics (pages 20, 26, 42, 54, 79, 117, 121, 123, 128).

He also brings attention to Gerritsen’s Australia and the Origins of Agriculture, an amateur but densely scholarly and demanding work that has been controversial among specialists.5 This is his most frequently used source.

Pascoe also popularises part of the important work by Paul Memmott, who presented the first comprehensive survey of classical-period Aboriginal dwellings.6

The British Empire and its ‘races’ in 1937.

Pascoe contradicts the false belief, perhaps held by some, that all Aboriginal people were naked all of the time. Some Aboriginal people sewed animal skins into cloaks (page 89).

He criticises the uninformed view that classical Aboriginal society consisted of constantly nomadic people who simply lived off nature’s bounty, were not ecological agents, did not stay in one place for more than a few days and did not store resources (for example, page 12).

And he gives considerable attention to the storage of foods (pages 105–14), this being a useful corrective to ignorance of Aboriginal storage methods.

Even here, however, the answer to the false belief that Aboriginal people stored nothing is not to assert that they universally amassed major stores of food. Many people stored a few food sources for shorter or longer periods, differing by region, and some stored almost nothing. Different climates set up different challenges for storage. Deserts were more friendly than hot, humid tropics. After long experience with bush-dwelling people in the Mitchell River area of CYP in the 1930s, trained anthropologist Lauriston Sharp noted that they were at one extreme end of the storage spectrum: the only item they stored beyond a day or two was the nonda plum.7

To Pascoe’s examples, a good number of them drawn from Gerritsen, could be added many more. Philip Clarke has provided a brief survey of evidence as to traditional storage that complements Pascoe’s.8 Clarke’s examples are mainly, but not only, drawn from the arid zone. One could also add, from the wet monsoon belt, the following. In the 1970s in the case of the Wik region of CYP, where I did intensive fieldwork with people who in many cases had been born and raised beyond the reach of the British Empire, I found that:

Limited food storage was practised. Nonda plums (Parinari nonda F. Muell. ex. Benth.) were dried on the rooves of shelters, or collected dry from the ground (the dry form even has a different name), and were kept for some weeks after their season of superabundance. Long yams (Dioscorea transversa R. Br.) were stored in the sand for weeks and even months.9 Long-necked turtles might survive a day or two trussed up, and in the Big Lake area barramundi is said to have been cooked, wrapped in paperbark, and buried in the cool earth for eating days later. Most food, however, was eaten within twenty-four hours.10

Labels and definitions

In the course of discussing Dark Emu in this book, we engage with the problem of labels for kinds of people that are focused on their economic lives. This problem looms large in Dark Emu. It should not be lightly dismissed on the grounds that names for types of subsistence are merely tags. The debate here is over not just labels but the way subsistence types are classified and compared.

In a talk given in 2018, Pascoe said: