1

Morris

March

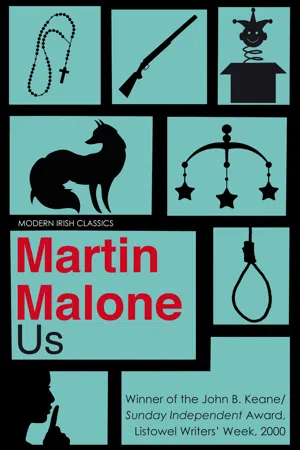

An unusual family. Us. There’s Dad who isn’t here but whose shadow is, and Mum who is here but whose heart is broken. There’s Gina who’s sad, and Karen who’s not. There’s Victor who’s intelligent, and me who isn’t. There was Adam, too, who hurt us more than we imagined we could be hurt.

We live in a large bungalow set in a corner of a field, near a crossroads. Dad farmed sheep and trained two racehorses. He did neither very well. We survived on what he made from selling off bits of the land and what he won from gambling. He is lucky at the horses. Back then, he only told us about his lucky days. He didn’t have to mention his bad ones, we knew by the puss of him, the way his eyes squinted, as though he were trying to squeeze piss out of them.

Mum tends to her face a lot. Fighting wrinkle advancement on every front with all sorts of creams. She’s losing the battle around her eyes, where the lines are deep. Dad used to tell her she could no sooner push back time than he could his belly-button. Mum didn’t speak with him all that much. I think she blamed him for the lines about her eyes. Mum and Dad acted like people who were extremely fed up with each other and didn’t know what to do about it. Dad is very small in Mum’s eyes and has been for a long time. We didn’t think he could get any smaller. But he did. This is how.

Mum has two friends who drop in a lot. She met Father Pat Toner through her best friend, Kay Walsh. They hold private meetings in the sitting-room, smoking, all crossing their legs as though they were afraid of farting in each other’s company.

Victor says they talk a lot of shit about shit. I know they cross their legs because I brought in tea on a tray, and they all went quiet and said thanks very much. And they all had their legs crossed. It looked funny. It just did. I don’t know why. Mum used to do that sometimes. Let off. We could be eating our dinner or anything. She blamed her stomach instead of her arse. Dad said she’s full of wind. When Dad found something he didn’t like about Mum, he sunk his teeth into it like a dog with a fresh bone. Anyway, Mum got the problem sorted out, so she doesn’t get embarrassed in front of us any more. Sometimes I wonder where all her wind goes. We didn’t mind her farting as much as we minded Dad for getting on to her. Nerves – I think Mum’s stomach nerves were shot for a while, shot from worrying, but now she’s sharing her worries with her friends, and I don’t hear them farting, so they must be able to handle the pressure.

A week leading up to what happened Adam, Gina told us all she was pregnant. She’s a very attractive redhead with a smooth figure. She wasn’t happy with her breasts, though, because I’d caught her a couple of times feeling herself in the mirror, and sighing this way and that, as if she were half-afraid of discovering something. I heard her telling Karen she’d go absolutely fucking crazy if she ever found a hair growing around her nipple. But I think she’s afraid of discovering something else now. Aunt Julie died before Christmas. And how she died affected all the women in our house something dreadful. Mum drove over to Doc Fleming in Kildare and got him to examine the lot of them. He booked them into a Dublin hospital for check-ups. Lately, Doc Fleming sends all his doubts to hospital. His confidence was shook when eight of his patients died in one week. Victor and me call him Doctor Doom, but not in front of the women.

Mum’s about the worst affected. Aunt Julie’s her sister. And they looked alike. She told Dad it was like looking at herself lying in the coffin. Of course, Dad had no drink in him, so he said nothing, just sat there in his armchair by the range, smoking his pipe. Probably wishing that it was Mum. Wishing with his eyes like he does with the horses he backs, wishing so hard it’s not wishing but praying.

After Gina told the lot of us she was pregnant, none of us could say anything. A guy on the news talked about English soccer fans going mad on the streets in Holland. Dad’s eyes went like grey slivers of steel. His cheeks went in, as though his heart had pulled on strings attached to them. Mum often said his heart was like a cactus, dry and spiky. We’d been eating our dinner. Mum puts a big effort into cooking the main evening meal. It’s the one meal she insists we’re all together for, in at the table, like a proper family. Once she tried to get us to say the Rosary, but praying together to stay together didn’t sit easy with us, not with Dad about. Victor told me that God had put all the Antichrists under the one roof and surrounded them with a moat of sheepshite.

We sat like zombies around the table. Mum’s hands were on her throat, checking to see that she hadn’t said she was pregnant. Karen’s eyes fell sleepy. She’d known, of course. No one can sneeze in this house without her knowing. But she didn’t know everything. I found out she didn’t later, when we got closer and didn’t pick on each other all the time. We thought Dad would lose his temper. Sometimes he does over nothing. He’d be so quiet in himself, and then he’d get thick about something: the TV being too loud, someone leaving a smell in the loo, one of us lazy about getting out of bed, stuff like that. Pregnant. Jesus.

Mum’s hands shot to her temples. Karen buried a nervous smile. Victor looked up from his book. He’s always reading, even at the table; he says his nerves can’t stand people making slopping noises. Adam had tracks on his teeth, so he probably made the most noise. He asked Victor what he wanted him to do – shove his food up his butt? Adam could be crude. Victor’s reading Robinson Crusoe. Must be for the fortieth time. He loves the idea of being away on a desert island, away from everyone. Though he says he’d have a preference for a Woman Friday. He thinks the author might have been a little queer to think up a Man Friday in the first place. Though the times he lived in might have had some bearing on his decision. They liked to keep the lid on their shit back then. Legs crossed, maybe?

Victor and me are twins. I’m thirteen years, four months and three days old. He’s two minutes older. He says on the way out he grabbed the only brains on offer. Karen says he grabbed the good looks too. She said that to spite me. But Victor is handsome. He has jet-black hair, lean features and large blue eyes you’d think a clear sky had spat into. My hair isn’t so dark, features aren’t so lean. My nose – well – Victor says whoever had it last time must have been a boxer … who jabbed with his snout.

Dad and Adam stared at each other. Gina stared at the two of them, then the rest of us.

Adam had his own room. He used to hand his shoes down to Dad. Mum blames the chemicals in the food chain for the kids being so tall these days; ‘big-feeted kids,’ she says, when she’s full of Bailey’s. Talking about Adam’s yacht-sized footwear parked on the hairmat. He never put away his shoes in the shoe cabinet Mum bought in Argos in Tallaght. She was always getting on to him about it. He never listened. He ignored her sometimes, just to annoy her.

‘Pregnant!’ Mum’s shriek pierced my thoughts.

Gina bit her lower lip.

‘How … who … you stupid little bitch. How could you be so stupid?’

Tears came to Gina’s eyes. Genuine, I’m sure. My sisters can do that: turn tears on and off at will.

‘Who?’ Mum demanded.

She wanted to know who so she could kill him. She couldn’t kill Gina, although part of her probably wanted to. Victor told me afterwards that some women blame men for getting them pregnant without realising they had something to do with it too. It proved, he said, how easily women can forget things when they want.

‘Terry,’ Gina said.

She said Terry as if the lot of us should know him.

A certain colour came to Adam’s cheeks. More purplish than red. His eyebrows moved up and down. He was seventeen. His face had fiery red pimples and his lips were thin as razor-blade edges. He’d light fairish hair which he kept smoothing and it was always gelled. Sometimes he put dyes in his fringe: blue and pink. He loved watching the wrestling on TV. His favourite wrestler was ‘The Undertaker’. I didn’t like it so much at the start, but I like it now. Adam used to practise his moves on me and Victor but Victor used to get so serious. He punched Adam on the nose and drew blood that pumped like it was never going to stop. Adam didn’t go crazy. He just paled. That finished the wrestling messing for us – Mum went spare. Victor said Adam had him pinned, what else could he do? Adam said Victor didn’t like being bested by anyone.

Dad hated the sport, said nancy boys played it, and that the whole thing was just a rig-up. We thought he was so anti-wrestling because it was Adam’s hobby. And Adam thought so too.

Dad jumped to his feet, his eyes full of storms. Looking at us as though we were to blame for Gina getting herself pregnant.

‘Terry who?’ Mum said, trying to keep calm. The fat of her upper arms jiggled and I thought how the needle-mark on her arm looked like a third eye. Gina thumbed her hair behind her ears. She has big ears, which is a good reason for wearing long hair. Karen’s ears aren’t so big, so her hair is tight. She likes to wear earrings and sometimes a stud in her nose.

‘Magee’ Gina breathed.

You’d know Gina was lying. But you’d have to know her to know. A signpost doesn’t come up on her head to tell you. Her soul has little ingredients: a drop of blush on her cheeks, a line of worry down her forehead, the way her forefinger touches the corner of her lip. Mum knows how to read the signs too. But she lets on she doesn’t. I think it’s because she can read other signs I haven’t learned to read yet.

Then Adam slunk away, shoulders hunched. He used to suffer from asthma, and kept an inhaler in his pocket. We could count on him going into hospital for a week every year, mostly when the fog rolled down from the mountain, or in summer when the sun was blistering. But he sort of grew out of it during a time when everyone thought he’d have asthma forever. Dad used to look at Adam like a sun-worshipper looking at a grey day, with disappointment. Victor said Dad failed to realise that Adam cared nothing for him either – each was bad weather to the other.

Karen shook her head. She’s not really into fellas, she says. She’s never going to get married or have babies. Ever. She used to like playing with my Action Men. Victor said it was because Action Man had no penis, and therefore did not constitute a threat to her.

Mum said to Karen, ‘Do you know who this fucker is?’

‘No,’ gulped Karen, ‘I don’t.’

She sat on her knees on the chair, elbows on the table, hands supporting her chin, looking at Gina as though she were watching a TV soap.

‘Where did you meet this lad?’ Mum said.

‘At a disco … Nijinski’s.’

‘When?’

‘About two months ago.’

‘Where does he live?’

Gina froze, then she broke down; tears streamed down her cheeks. Her shuddering something terrible. Her hands slapping her face, and when that didn’t hurt her enough, they started tugging at her lovely red hair. Mum and Karen pulling at her, trying to get her to stop, which I thought was all weird, given that Gina was doing to herself what Mum wanted to do to her. They stopped her just as Victor touched my arm and nodded for us to leave. That’s something I like about Victor. He knows when it’s the right time to leave. He doesn’t wait to be told, like I normally do. In our bedroom, he climbe...